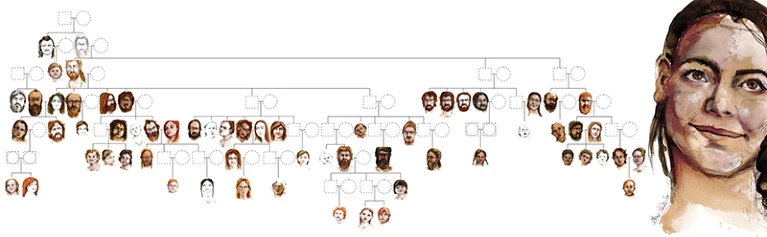

DNA Reveals Neolithic Family Tree in France

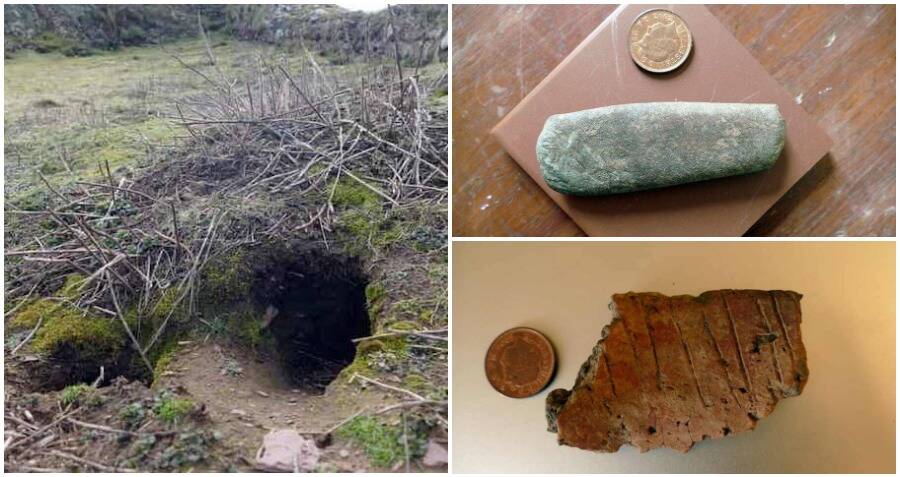

In the mid-2000s, archaeologists excavating a burial site in France uncovered a 6,500-year-old mystery. Among the remains of more than 120 individuals, one grave stood out.

It contained a nearly complete female skeleton alongside a few assorted bones that looked like they had been dug up and moved from another grave.

Ancient DNA from the enigmatic relocated remains now shows that they belonged to the male ancestor of dozens of the other people buried nearby.

This insight comes from a study that used ancient genomics to build the largest-ever genealogy of a prehistoric family, providing a snapshot of life in an early farming community. The study1 was published on 26 July in Nature.

Ordinary folk

Western Europe is littered with monuments that served as burying grounds for high-status individuals from a period, roughly 7,000 to 4,000 years ago, called the Neolithic.

The dozens of burials at Gurgy ‘Les Noisats’, located about 150 kilometers southeast of Paris, lack any signs of such monuments or rich grave goods, indicating that they might have belonged to commoners, says study co-author Wolfgang Haak, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

His team analysed the genomes of 94 of the 128 individuals recovered from the site, and used the data to determine how they were related to one another.

The researchers expected some individuals to be related, based on the composition of other Neolithic sites.

But they were astounded to discover that around two-thirds belonged to a single family tree that spanned seven generations. The closer people were buried, the more closely related they were.

At the top of the genealogy is the man from the mysterious grave. The jumble of bones was unique to the site, yet no grave goods or other evidence signalled his position or the reason his remains had been exhumed, says study co-author Maïté Rivollat, an archaeologist at the University of Ghent in Belgium.

The researchers have so far failed to extract DNA from the woman buried alongside him. If she is like the other adult women from the site — most of whom were not closely related to anyone else — she might have joined the family from another community.

This points to a social structure similar to those uncovered at some other prehistoric sites in which male descendants tended to stick around, whereas the women moved elsewhere.

Prehistoric social scene

The giant family tree revealed other previously hidden aspects of Neolithic life. All siblings shared the same mother and father, with no-half siblings present.

This suggests that no individuals had multiple partners. “Here it’s fairly straightforward and fairly monogamous,” says Haak. “Is that the standard life of the commoner and the non-elite?”

This contrasts with a later Neolithic burial in the United Kingdom, Hazleton North, where researchers identified a man who had reproduced with four women.

Researchers must build family trees from other ancient burials to figure out what is typical, says Chris Fowler, an archaeologist at the University of Newcastle, UK, who was part of that study.

“This type of work really breathes new life into our understanding of ancient peoples,” says Kendra Sirak, an ancient-DNA specialist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. She’s most curious about the man at the root of the family tree. “I would love to know what made this person so important.”