Can 4.5 Billion-Year-Old Meteorite Hold Secrets of Life on Earth?

Scientists are set to uncover the secrets of a rare meteorite and possibly the origins of oceans and life on Earth, thanks to Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) funding.

Research carried out on the meteorite, which fell in the UK earlier this year, suggests that the space rock dates back to the beginning of the Solar System, 4.5 billion years ago.

The meteorite has now been officially classified, thanks in part to the STFC-funded studies on the sample.

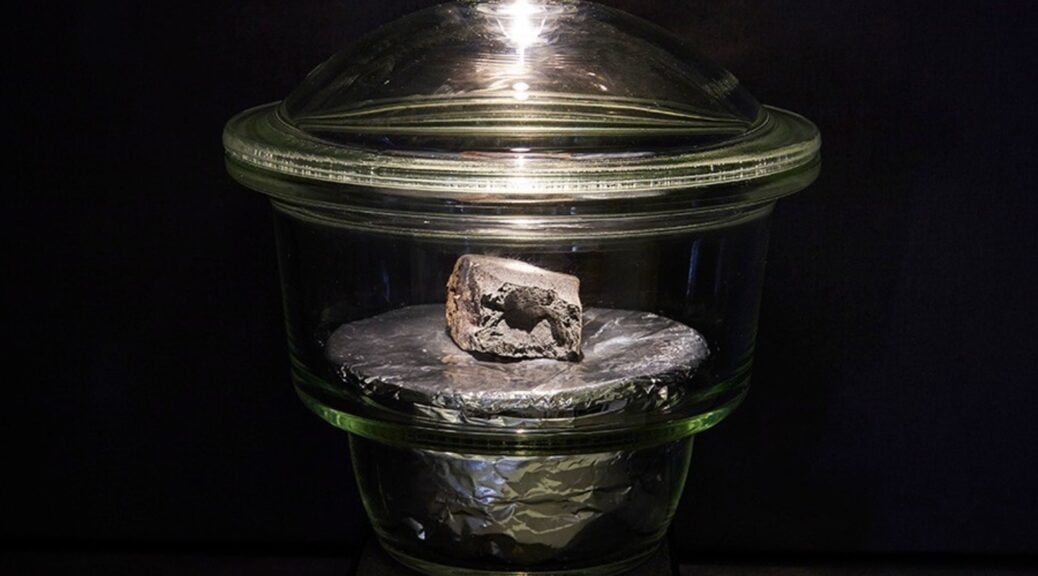

The Winchcombe meteorite, aptly named after the Gloucestershire town where it landed, is an extremely rare type called a carbonaceous chondrite.

It is a stony meteorite, rich in water and organic matter, which has retained its chemistry from the formation of the solar system. Initial analyses showing Winchcombe to be a member of the CM (“Mighei-like”) group of carbonaceous chondrites have now been formally approved by the Meteoritical Society.

STFC provided an urgency grant in order to help fund the work of planetary scientists across the UK. The funding has enabled the Natural History Museum to invest in state-of-the-art curation facilities to preserve the meteorite, and also supported time-sensitive mineralogical and organic analyses in specialist laboratories at several leading UK institutions.

Dr. Ashley King, a UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Future Leaders Fellow in the Department of Earth Sciences at the Natural History Museum, said: “We are grateful for the funding STFC has provided.

Winchcombe is the first meteorite fall to be recovered in the UK for 30 years and the first-ever carbonaceous chondrite to be recovered in our country. STFC’s funding is aiding us with this unique opportunity to discover the origins of water and life on Earth. Through the funding, we have been able to invest in state-of-the-art equipment that has contributed to our analysis and research into the Winchcombe meteorite.”

The meteorite was tracked using images and video footage from the UK Fireball Alliance (UKFAll), a collaboration between the UK’s meteor camera networks that includes the UK Fireball Network, which is funded by STFC. Fragments were then quickly located and recovered.

Since the discovery, UK scientists have been studying Winchcombe to understand its mineralogy and chemistry to learn about how the Solar System formed.

Dr. Luke Daly from the University of Glasgow and co-lead of the UK Fireball Network said: “Being able to investigate Winchcombe is a dream come true.

Many of us have spent our entire careers studying this type of rare meteorite. We are also involved in JAXA’s Hayabusa2 and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx missions, which aim to return pristine samples of carbonaceous asteroids to the Earth.

For a carbonaceous chondrite meteorite to fall in the UK, and for it to be recovered so quickly and have a known orbit, is a really special event and a fantastic opportunity for the UK planetary science community.”

Funding from STFC enabled scientists to quickly begin the search for signs of water and organics in Winchcombe before it could be contaminated by the terrestrial environment.

Dr. Queenie Chan from Royal Holloway, University of London added: “The team’s preliminary analyses confirm that Winchcombe contains a wide range of organic material! Studying the meteorite only weeks after the fall, before any significant terrestrial contamination, means that we really are peering back in time at the ingredients present at the birth of the solar system, and learning about how they came together to make planets like the Earth.”

A piece of the Winchcombe meteorite that was recovered during an organized search by the UK planetary science community is now on public display at London’s Natural History Museum.