‘I don’t care’: text shows modern poetry began much earlier than believed

New research into a little-known text written in ancient Greek shows that “stressed poetry,” the ancestor of all modern poetry and song, was already in use in the 2nd Century CE, 300 years earlier than previously thought. In its shortest version, the anonymous four-line poem reads “they say what they like; let them say it; I don’t care.” Other versions extend with “Go on, love me; it does you good.”

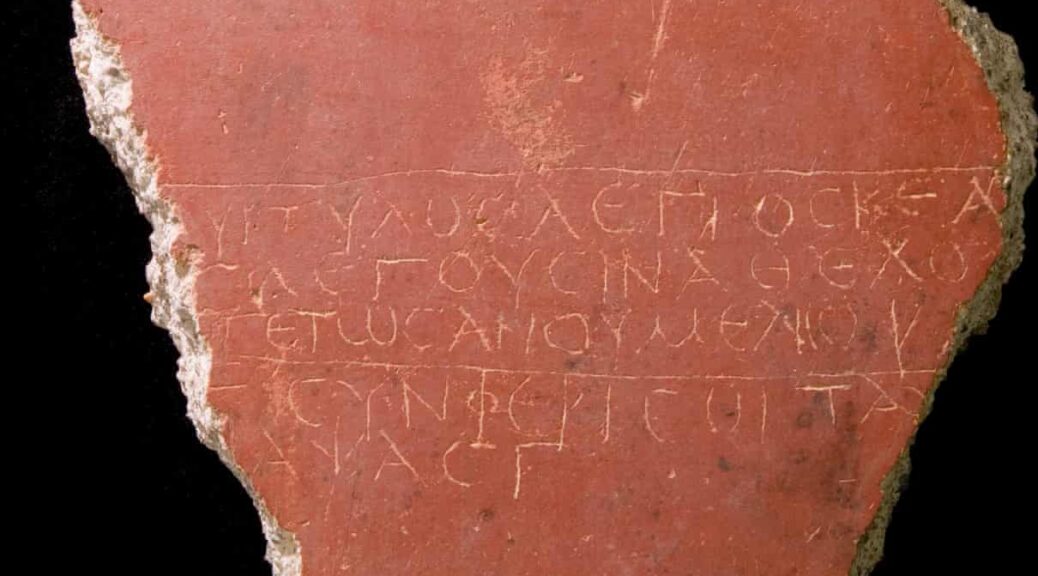

The experimental verse became popular across the Eastern Roman Empire and survives because, as well as presumably being shared orally, it has been found inscribed on twenty gemstones and as a graffito in Cartagena, Spain.

By comparing all of the known examples for the first time, Cambridge’s Professor Tim Whitmarsh (Faculty of Classics) noticed that the poem used a different form of meter to that usually found in ancient Greek poetry. As well as showing signs of the long and short syllables characteristic of traditional “quantitative” verse, this text employed stressed and unstressed syllables.

Until now, “stressed poetry” of this kind has been unknown before the fifth century when it began to be used in Byzantine Christian hymns.

Professor Whitmarsh says: “You didn’t need specialist poets to create this kind of musicalized language, and the diction is very simple, so this was a clearly a democratizing form of literature. We’re getting an exciting glimpse of a form of oral pop culture that lay under the surface of classical culture.”

The new study, published in The Cambridge Classical Journal, also suggests that this poem could represent a “missing link” between the lost world of ancient Mediterranean oral poetry and song, and the more modern forms that we know today.

The poem, unparalleled so far in the classical world, consists of lines of 4 syllables, with a strong accent on the first and a weaker on the third. This allows it to slot into the rhythms of numerous pop and rock songs, such as Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.”

Whitmarsh says: “We’ve known for a long time that there was popular poetry in ancient Greek, but a lot of what survives takes a similar form to traditional high poetics. This poem, on the other hand, points to a distinct and thriving culture, primarily oral, which fortunately for us in this case also found its way onto a number of gemstones.”

Asked why the discovery hasn’t been made before, Whitmarsh says: “These artefacts have been studied in isolation. Gemstones are studied by one set of scholars, the inscriptions on them by another. They haven’t been seriously studied before as literature. People looking at these pieces are not usually looking for changes in metrical patterns.”

Whitmarsh hopes that scholars of the medieval period will be pleased: “It confirms what some medievalists had suspected, that the dominant form of Byzantine verse developed organically out of changes that came about in classical antiquity.”

In its written form (which shows some minor variation), the poem reads:

Λέγουσιν: They say

ἃ θέλουσιν: What they like

λεγέτωσαν: Let them say it

οὐ μέλι μοι: I don’t care

σὺ φίλι με: Go on, love me

συνφέρι σοι: It does you good

The gemstones on which the poem was inscribed were generally agate, onyx or sardonyx, all varieties of chalcedony, an abundant and relatively inexpensive mineral across the Mediterranean region.

Archaeologists found the most beautiful and best-preserved example around the neck of a young woman buried in a sarcophagus in what is now Hungary. The gem is now held in Budapest’s Aquincum Museum.

Whitmarsh believes that these written accessories were mostly bought by people from the middle ranks of Roman society. He argues that the distribution of the gemstones from Spain to Mesopotamia sheds new light on an emerging culture of “mass individualism” characteristic of our own late-capitalist consumer culture.

The study points out that “they say what they like; let them say it; I don’t care” is almost infinitely adaptable, to suit practically any countercultural context. The first half of the poem would have resonated as a claim to philosophical independence: the validation of an individual perspective in contrast to popular belief. But most versions of the text carry an extra two lines which shift the poem from speaking abstractly about what “they” say to a more dramatic relationship between “you” and the “me.” The text avoids determining a specific scenario but the last lines strongly suggest something erotic.

The meaning could just be interpreted as “show me affection and you’ll benefit from it” but, Whitmarsh argues, the words that “they say” demand to be reread as an expression of society’s disapproval of an unconventional relationship. The poem allowed people to express a defiant individualism, differentiating them from trivial gossip, the study suggests. What mattered instead was the genuine intimacy shared between “you” and “me,” a sentiment which was malleable enough to suit practically any wearer.

Such claims to anticonformist individuality were, however, pre-scripted, firstly because the ‘careless’ rhetoric was borrowed from high literature and philosophy, suggesting that the owners of the poetic gems did, after all, care what the classical litterati said. And secondly, because the gemstones themselves were mass-produced by workshops and exported far and wide.

Whitmarsh says: “I think the poem appealed because it allowed people to escape local pigeon-holing, and claim participation in a network of sophisticates who ‘got’ this kind of playful, sexually-charged discourse.”

“The Roman Empire radically transformed the classical world by interconnecting it in all sorts of ways. This poem doesn’t speak to an imposed order from the Imperial elite but a bottom-up pop culture that sweeps across the entire empire. The same conditions enabled the spread of Christianity; and when Christians started writing hymns, they would have known that poems in this stressed form resonated with ordinary people.”

Whitmarsh made his discovery after coming across a version of the poem in a collection of inscriptions and tweeting that it looked a bit like a poem but not quite. A Cambridge colleague, Anna Lefteratou, a native Greek speaker, replied that it reminded her of some later medieval poetry.

Whitmarsh says: “That prompted me to dig under the surface and once I did that these links to Byzantine poetry became increasingly clear. It was a lockdown project really. I wasn’t doing the normal thing of flitting around having a million ideas in my head. I was stuck at home with a limited number of books and re-reading obsessively until I realized this was something really special.”

There is no global catalogue of ancient inscribed gemstones and Whitmarsh thinks there may be more examples of the poem in public and private collections, or waiting to be excavated.