A 3,400-year-old Minoan tomb has been uncovered in an unnamed farmer’s olive grove near Ierapetra on the Greek island of Crete

The untouched Bronze Age tomb and the skeletons inside will hopefully provide archaeologists with information about the mysterious Minoan civilization.

In an extraordinary example of being in the wrong place at the right time, a Greek farmer just made a startling archaeological discovery.

A 3,400-year-old Minoan tomb was uncovered in an unnamed farmer’s olive grove near the city of Ierapetra on the Greek island of Crete. According to Cretapost, the farmer was attempting to park his car underneath an olive tree when suddenly the ground beneath him began to sink.

The farmer pulled his car out from under the tree and noticed that a huge hole which measured around four feet wide had opened up where his car had been sitting. When he peeked into the hole, the farmer knew he had stumbled upon something special. He called the local heritage ministry, Lassithi Ephorate of Antiquities, to investigate.

The archaeologists from the ministry excavated the hole. What they found next was unprecedented.

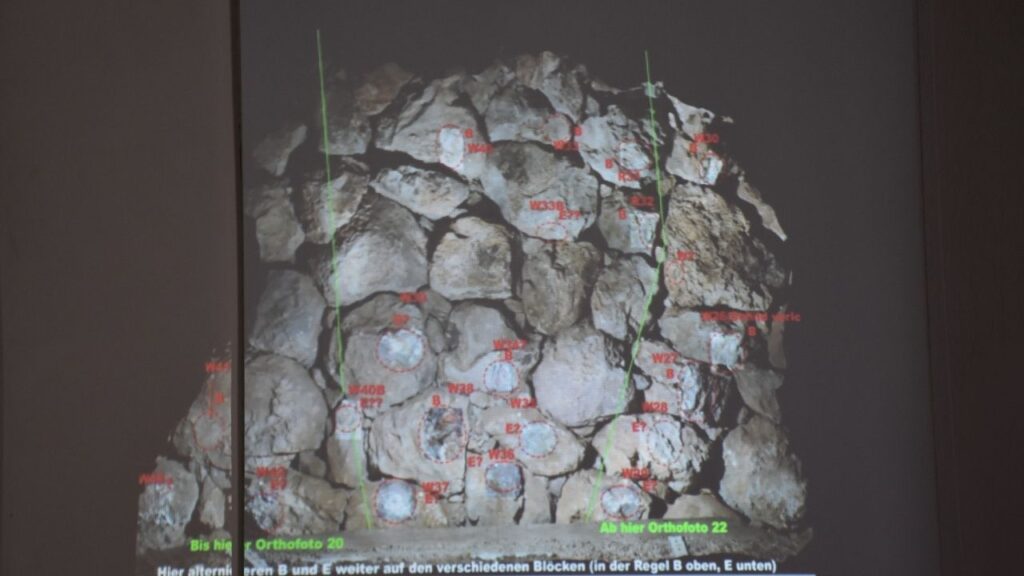

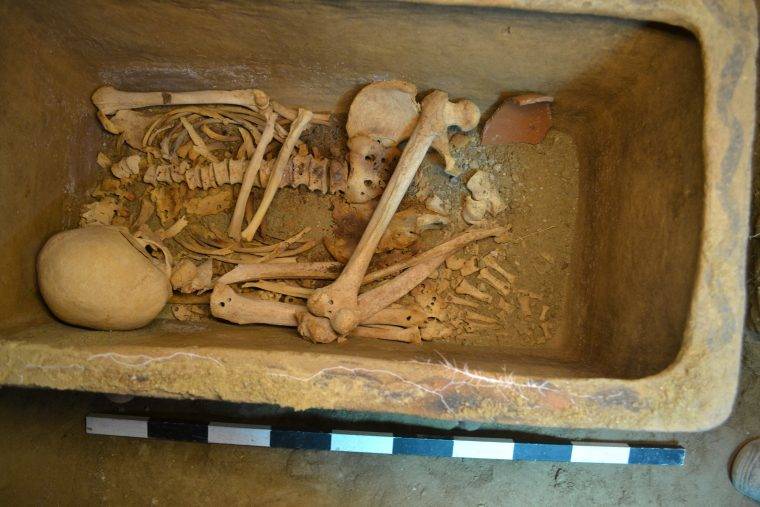

The pit was approximately four feet wide and eight feet deep, was divided into three sections, and very apparently was a tomb.

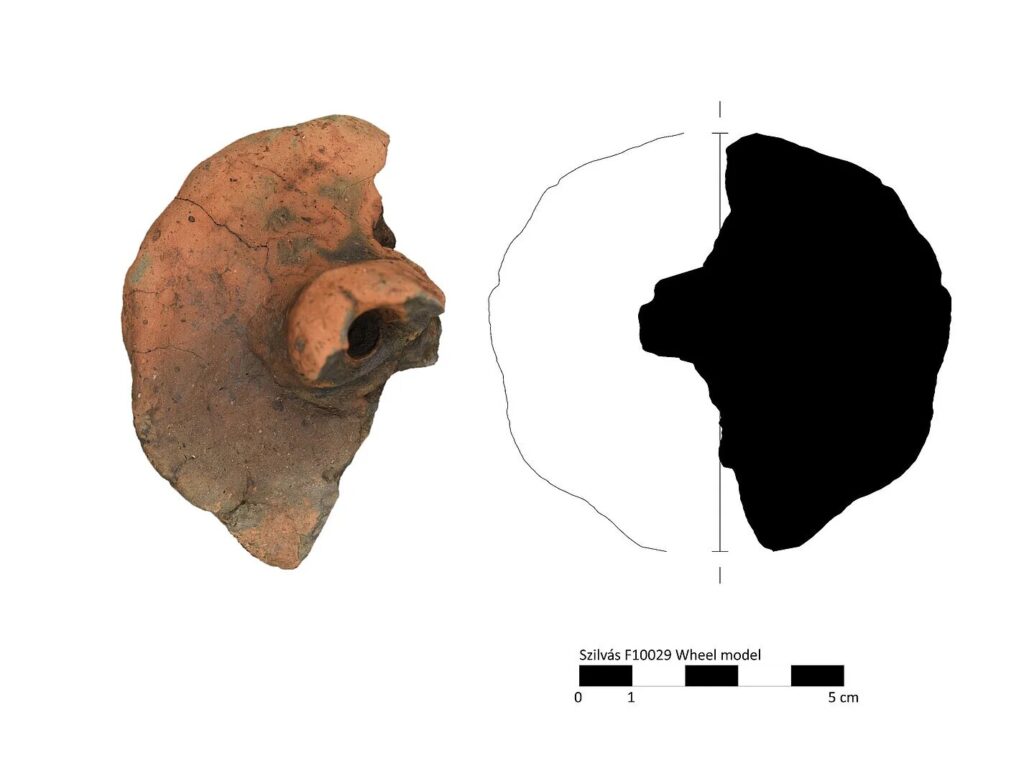

In the first section, archaeologists uncovered a coffin and a variety of artifacts. The following niche held a second coffin, 14 Greek jars called amphorae, and a bowl.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the archaeologists identified that the tomb was Minoan and of the Bronze Age due to the style of coffin they found. The artifacts — funerary vases and the two coffins— were well-preserved despite their extremely old age.

The tomb was sealed off by a stone wall and only after thousands of years of wear and tear did it deteriorate enough to buckle under the weight of the farmer’s car.

“Soil retreat was a result of the watering of the olive trees in the area as well as a broken irrigation tube,” Argyris Pantazis, the Deputy Mayor of Local Communities, Agranian and Tourism of Ierapetra, told Cretapost. “The ground had partially receded, and when the farmer tried to park in the shade of the olive, it completely retreated.”

Pantazis also said that the fact that the tomb was untouched by thieves for millennia makes it an ideal site for archaeologists to learn as much as possible about the two people buried in the tomb and life for the Minoan civilization.

According to Forbes, the skeletons date back to the Late Minoan IIIA-B period in archaeological chronology, also known as the Late Palace Period.

So far, not much information is known about the Minoan civilization and their way of life, save for their labyrinth palatial complexes, showcased in classic myths like Theseus and the Minotaur.

Researchers also believe that the Minoans met their end because of a string of devastating natural disasters. Most other details of the Minoan’s history remain unclear.

Further analysis of the skeletons and artifacts in the tomb in Crete will hopefully help archaeologists fill in some blanks and answer questions about mysterious Minoan civilization.