Los Millares- The Largets Known Fortified Neolithic Settlement in Europe

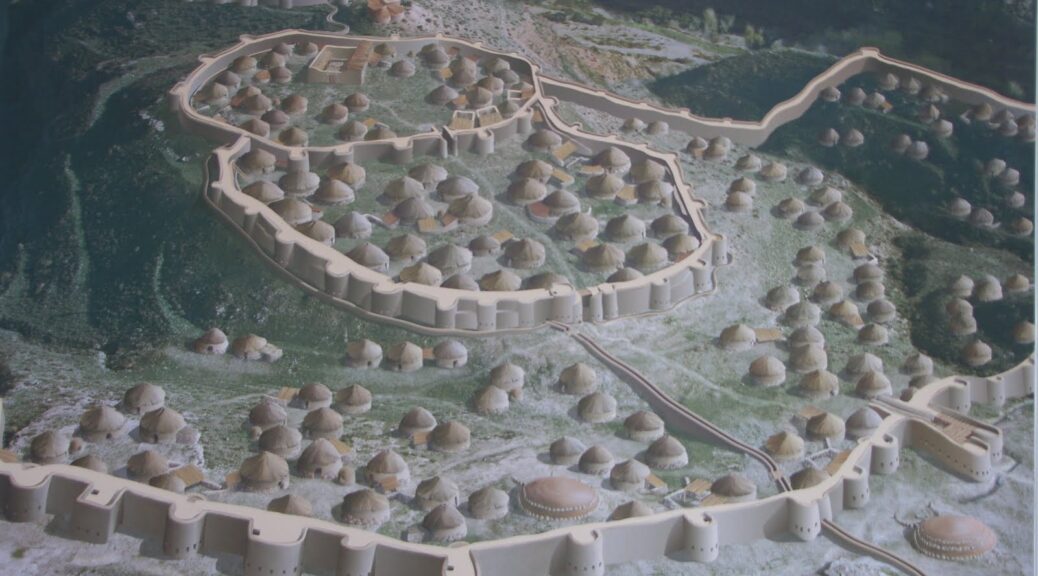

Just 17km from Almería between Santa Fe de Mondujar y Gádor lies Los Millares, the largest known European fortified Neolithic settlement, dated c. 3,200-2,300 BC. The site includes a settlement and a cemetery with over 80 megalithic tombs.

Three walls and an inner citadel with an elaborate fortified entrance make up part of extensive fortifications at Los Millares. Thirteen nearly circular enclosures were forts protecting it. Within the three walls are 80 passage graves.

Los Millares was constructed in three phases, each phase increasing the level of fortification. The fortification is not unique to the Mediterranean area of the 3rd millennium; other sites with bastions and defensive towers include the sites of Jericho, Ai, and Aral (in Palestine) and Lebous, Boussargues and Campe of Laures (in France).

It consists of a settlement, guarded by numerous outlying forts and a cemetery of passage tombs and covers around 5 acres.

Three concentric walls with four bastions surrounded the settlement itself; radiocarbon dating has established that one wall collapsed and was rebuilt around 3,025 BC. A cluster of simple dwellings lay inside the walls as well as one large building containing evidence of copper smelting.

Finally, the fortified citadel at the very top of the spur has only been investigated so far by means of various pilot trenches, which have revealed walls up to six metres thick, confirming the great importance of the structure. Within its grounds, there is a deep hollow, which is thought to be a water cistern but so far has not been excavated.

Los Millares was discovered in 1891 during the course of the construction of a railway and was first excavated by Luis Siret in the succeeding years.

Antonio Arribas and Fernando Molina from the University of Granada later excavated Los Millares from 1978-1995, and analysis continues on the massive amounts of information collected.

The strategic sequence of the site shows that the settlement went through various phases of occupation. The first was during the early copper age (3,200 to 2,800 B.C.) when the three interior walls were constructed.

The second was during the middle copper age (2,800 to 2,450 B.C.), when the innermost wall was demolished and the outer wall constructed, together with most of the small forts outside the settlement itself. Finally, in the late copper age (2,450 to 2,250 B.C.) the first bell beakers appeared, a form of pottery that was produced henceforth on a large scale in the village.

During this late period, some profound social upheaval brought about a gradual decline in the size of the settlement, whose inhabitants gradually retired towards the fortified citadel. The site appears to have been finally abandoned around 2,250 B.C.

Over eighty megalithic tombs are visible outside the settlement. The majority are of the type mentioned above, but tombs without corbelled roofs also exist.

The chronology of tomb construction and use is unclear, but analysis of tomb forms, sizes, numbers of burials, contents, and distributions suggests that the dead were selected for interment and that social ranking had emerged, with higher-ranked groups being buried in tombs located close to the settlement.

Similar Tholos Tombs are common in Mycenaean remains, and a connection is commonly suggested. They are also present at other places in Spain, noticeably at the Cueva de Viera, which sits beside the great Cueva de Menga passage mound. Holed stones are also a common feature of dolmens in the Caucasus region of Russia where hundreds are visible.

Large sheets of slate that were punched through and rounded off to make the entrances we see today, divided entrances. The chambers of the Tholos were lined with vertical slabs of slate, often painted red, sometimes with small niches present (used for the burial of children). The graves were finally covered over with conical mounds of earth and stones.

Many were given an outer skirting of slabs or masonry to strengthen the structure. Almost all the tombs were orientated east of southeast, except for a small group of seven mounds that were orientated southwest.

The tombs were collective with the number of skeletons discovered ranging from a dozen to over a hundred. Burial offerings included objects such as ivory and ostrich eggshell, copper tools, pottery vessels, arrowheads and flint knives.

The presence of such great quantities of mineral resources in the region is likely to be part of the reason for the existence of Los Millares in the first place. The parallel with the Minoans continues in the addition of arsenic as an antioxidant to their copper products. Arsenic is readily available in the local region of Sierra de Gador. Among the buildings dedicated to specialised activities, two areas have been identified as having once housed metallurgical workshops. While along the northern stretch of the outer wall there are several squares and round buildings dedicated to this, the best-preserved workshop is situated in a large rectangular building attached to the inner facade of the third line of fortification. Of considerable size, about 8m long by 6.5m wide, it was built with a solid masonry technique, with a door opening to the east. Inside are the remains of three structures: a mass of 1.3m in diameter with fragments of copper ore, a furnace delineated by a ring of clay with a depression at its centre to put the pot furnaces, and a small structure with slabs of slate in its northeast corner. It is suggested that this building was never roofed, as there is no post-holes present.