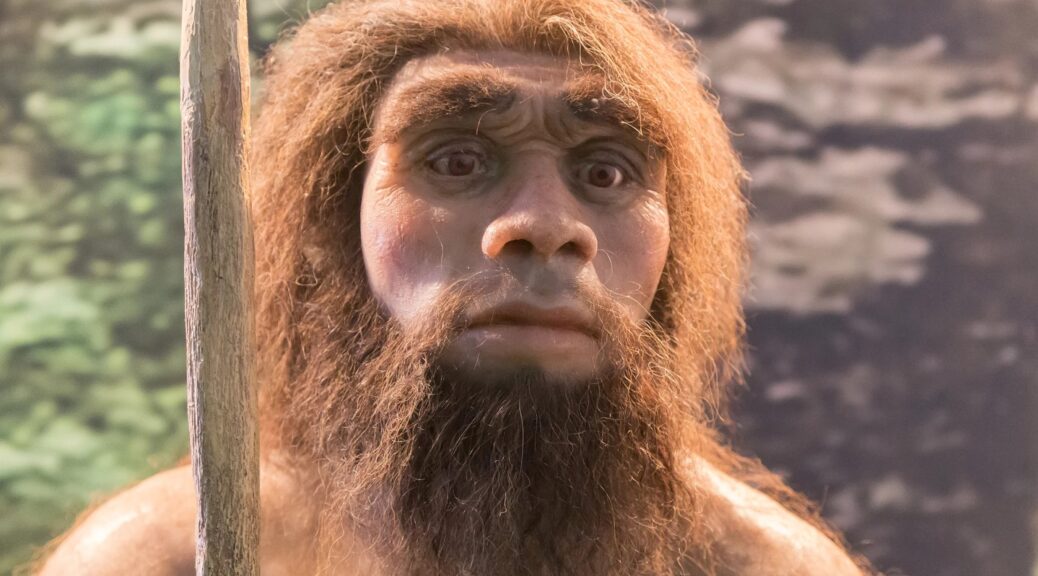

50,000-Year-old Neanderthal Microbiome Analyzed

Neanderthals’ gut microbiota already included some beneficial micro-organisms that are also found in our own intestine. An international research group led by the University of Bologna achieved this result by extracting and analyzing ancient DNA from 50,000-year-old fecal sediments sampled at the archaeological site of El Salt, near Alicante (Spain).

Published in Communication Biology, their paper puts forward the hypothesis of the existence of ancestral components of human microbiota that have been living in the human gastrointestinal tract since before the separation between the Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals that occurred more than 700,000 years ago.

“These results allow us to understand which components of the human gut microbiota are essential for our health, as they are integral elements of our biology also from an evolutionary point of view” explains Marco Candela, the professor of the Department of Pharmacy and Biotechnology of the University of Bologna, who coordinated the study.

“Nowadays there is a progressive reduction of our microbiota diversity due to the context of our modern life: this research group’s findings could guide us in devising diet- and lifestyle-tailored solutions to counteract this phenomenon.”

The Issues of the “Modern” Microbiota

The gut microbiota is the collection of trillions of symbiont micro-organisms that populate our gastrointestinal tract. It represents an essential component of our biology and carries out important functions in our bodies, such as regulating our metabolism and immune system and protecting us from pathogenic micro-organisms.

Recent studies have shown how some features of modernity — such as the consumption of processed food, drug use, life in hyper-sanitized environments — lead to a critical reduction of biodiversity in the gut microbiota. This depletion is mainly due to the loss of a set of microorganisms referred to as “old friends.”

“The process of depletion of the gut microbiota in modern western urban populations could represent a significant wake-up call,” says Simone Rampelli, who is a researcher at the University of Bologna and first author of the study. “This depletion process would become particularly alarming if it involved the loss of those microbiota components that are crucial to our physiology.”

Indeed, there are some alarming signs. For example, in the West, we are witnessing a dramatic increase in cases of chronic inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and colorectal cancer.

How the “Ancient” Microbiota Can Help

How can we identify the components of the gut microbiota that are more important for our health? And how can we protect them with targeted solutions? This was the starting point behind the idea of identifying the ancestral traits of our microbiota — i.e. the core of the human gut microbiota, which has remained consistent throughout our evolutionary history.

Technology nowadays allows to successfully rise to this challenge thanks to a new scientific field, paleomicrobiology, which studies ancient microorganisms from archaeological remains through DNA sequencing.

The research group analyzed ancient DNA samples collected in El Salt (Spain), a site where many Neanderthals lived. To be more precise, they analyzed the ancient DNA extracted from 50,000 years old sedimentary feces (the oldest sample of fecal material available to date). In this way, they managed to piece together the composition of the micro-organisms populating the intestine of Neanderthals. By comparing the composition of the Neanderthals’ microbiota to ours, many similarities aroused.

“Through the analysis of ancient DNA, we were able to isolate a core of microorganisms shared with modern Homo sapiens,” explains Silvia Turroni, a researcher at the University of Bologna and first author of the study.

“This finding allows us to state that these ancient micro-organisms populated the intestine of our species before the separation between Sapiens and Neanderthals, which occurred about 700,000 years ago.”

Safeguarding the Microbiota

These ancestral components of the human gut microbiota include many well-known bacteria (among which Blautia, Dorea, Roseburia, Ruminococcus and Faecalibacterium) that are fundamental to our health. Indeed, by producing short-chain fatty acids from dietary fiber, these bacteria regulate our metabolic and immune balance.

There is also the Bifidobacterium: a microorganism playing a key role in regulating our immune defences, especially in early childhood. Finally, in the Neanderthal gut microbiota, researchers identified some of those “old friends.” This confirms the researchers’ hypotheses about the ancestral nature of these components and their recent depletion in the human gut microbiota due to our modern life context.

“In the current modernization scenario, in which there is a progressive reduction of microbiota diversity, this information could guide integrated diet- and lifestyle-tailored strategies to safeguard the micro-organisms that are fundamental to our health,” concludes Candela. “To this end, promoting lifestyles that are sustainable for our gut microbiota is of the utmost importance, as it will help maintain the configurations that are compatible with our biology.”

Reference: “Components of a Neanderthal gut microbiome recovered from fecal sediments from El Salt” by Simone Rampelli, Silvia Turroni, Carolina Mallol, Cristo Hernandez, Bertila Galván, Ainara Sistiaga, Elena Biagi, Annalisa Astolfi, Patrizia Brigidi, Stefano Benazzi, Cecil M. Lewis Jr., Christina Warinner, Courtney A. Hofman, Stephanie L. Schnorr and Marco Candela, 5 February 2021,