A Dog Named Monty Has Dug Up a Rare Cache of Bronze Age Artifacts in the Czech Republic

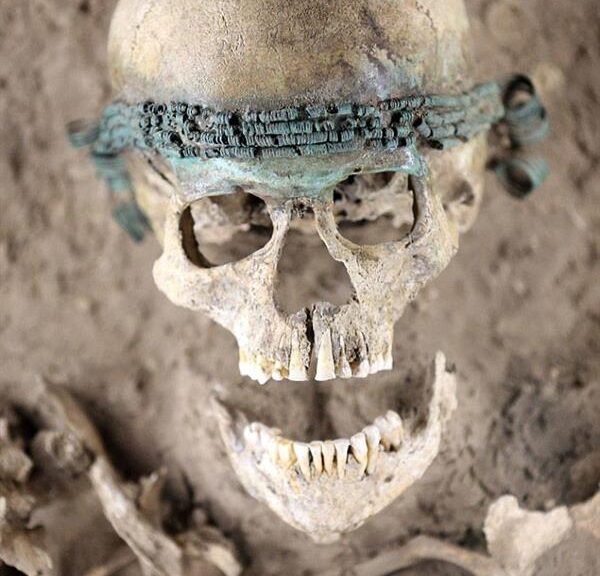

In March, Monty was out on a trip with his owner Mr. Frankota, to Orlické Mountains (northeast Bohemia), making a spectacular discovery. Archeologists report that the objects discovered by the dog are “surprisingly” in good condition.

Archeopupper

Frankota recounts that Monty rushed off during their walk and started digging frantically. He walked over to check what got his dog so excited and was surprised to see a collection of bronze objects.

The stash — which has been donated to the Hradec Králové Region local government — contained 13 sickle blades, 3 axe blades, and two spearheads.

All items were fashioned out of bronze. The wealth of objects, as well as the excellent condition they were buried in, points to a ritual deposit, archeologists believe.

“The fact that there are so many objects in one place is almost certainly tied to an act of honoration, most likely a sacrifice of some sorts,” Martina Beková, an archaeologist at the nearby Museum and Gallery of Orlické Mountains, told Czech Radio.

“What particularly surprised us was that the objects were whole, because the culture that lived here at the time normally just buried fragments, often melted as well. These objects are beautiful, but the fact that they are complete and in good condition is of much more value to us.”

Beková was part of the team that examined the artifacts after Frankota delivered them to local authorities.

They were likely produced by the Urnfield culture, a late Bronze Age Indo-European people that lived in the area. Their name stems from the group’s mortuary practices: they would cremate their dead and bury them in urns in fields.

As of now, the team cannot say for sure how or why the items were buried in the area.

The discovery has local archeologists excited — and rightly so. It’s the largest single finding in the region. They’re currently combing the region with metal detects but, so far, their search proved unfruitful. Still, they’re not about to give up just yet.

“There were some considerable changes to the surrounding terrain over the centuries, so it is possible that the deeper layers are still hiding some secrets,” Sylvie Velčovská from the local regional council.

The artifacts are currently on display as part of the exhibition Journey to the Beginning of Time at the Museum and Gallery of Orlické Mountains, Rychnov, until 21 October 2018. After that, they will undergo conservation and be moved to a permanent exhibition in a museum in Kostelec.

The team also wants to point out that archeologists often work with lucky discoveries made by members of the public or during excavation works; if you happen to stumble into some artifacts, you should notify local authorities (archeological items are considered government property in most states). It’s not a one-sided deal, either: Frankota was awarded 7,860 CZK (roughly US$360) for the items.

Hopefully, some of that will go towards buying Monty some well-deserved treats.