Rare, Neolithic ‘Goddess’ Figurine Discovered in Turkey

The finding happened in the southern part of Anatolian Plateau in central Turkey, one of the main proto-city centres of the first settlers and one of the world’s most renowned archaeological sites.

For a thousand years between 7100 and 6000 BC, i.e. the Neolithic period, Çatalhöyük has been continuously inhabited.

In 2016 the figure was found. In Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, the conclusions of his expert analyses are presented.

The best-known artifacts from this location are clay female figures which, due to their giant stance and bare breasts have been regarded as mother goddesses.

Today, they are usually interpreted as depicting the elderly and objects related to ancestor worship.

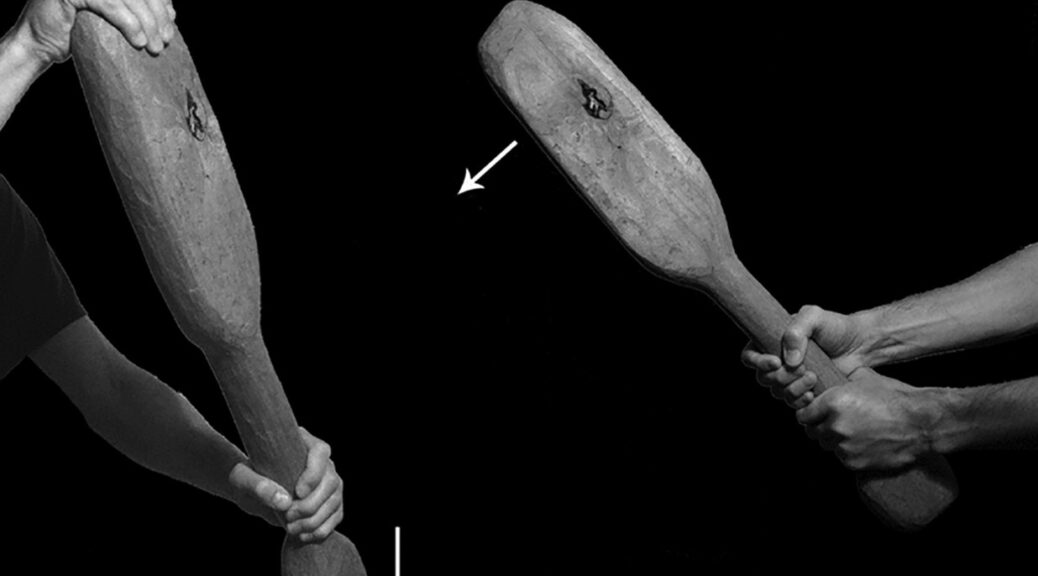

Now scientists have announced the discovery of a bone figurine that is anthropomorphic, i.e. has human features.

This is undoubtedly an important find with a very simplified, but clear depiction of human features in the form of eyes.

The figurine was made of bone, the proximal finger of a donkey`, told the PAP the discoverer of the object, Professor Kamilla Pawłowska, archaeozoologist and palaeontologist from the Department of Palaeoenvironmental Research of the Institute of Geology, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań.

The figurine is about 6 cm high. It has clearly visible incisions shaped to resemble eyes. A similar way of presenting human features is known from artefacts discovered in other sites in the Middle East from the same period, says Professor Kamilla Pawłowska.

She adds that the majority of similar objects are known from a bit later period, the Chalcolithic (4300 – 3300 BC). They are also made of bones, mainly donkey and horse.

Until now, during the research in Çatalhöyük scientists discovered the phalanges of donkeys and horses. They are often well preserved.

In individual cases, there were traces of processing on them, but never in a form reminiscent of human anatomical features, emphasizes Professor Kamilla Pawłowska.

The researcher says that there were not many donkeys in this prehistoric city, especially at the end of its functioning. Sheep and goats were more common since their meat, marrow and fat was an important element of the inhabitants` diet.

The figurine was discovered during the work of an international team under the supervision of Dr Marek Z. Barański from the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk.

Professor Kamilla Pawłowska found it while analysing the flotation sample, i.e. wet screening. This procedure allows archaeologists to find bone remains and other small artefacts.

It is known that the figurine was in one of the clay containers in a room where the food was stored. The container was made ca. 6500-6300 BC. (PAP)