Underwater Ruins of 3,000-Year-Old Castle Discovered in Turkey

Marine archaeologists made a superb find at the bottom of Turkey’s largest lake – a very well-preserved castle dating back 3,000 years. It was likely built by the mysterious Urartian civilization which inhabited the surroundings of Lake Van during the Iron Age.

Although locals have long reported legends of ancient ruins under the water, divers had investigated the lake for almost a decade before finding the fortifications.

Hurriyet Daily News reports that the research team discovered numerous other features of interest during this time period, including stalagmites that were at least 10 meters (33 feet) long, known as ‘underwater fairy chimneys’, pearl mullets, and a sunken Russian ship, but the ancient ruins had proved elusive until now.

Underwater Castle

The recent finding of the underwater fortifications was made by a team of researchers, including Tahsin Ceylan, an underwater photographer and videographer, diver Cumali Birol, and Mustafa Akkuş, an academic from Van Yüzüncü Yıl University.

The castle, which had been built during the Iron Age, when water levels were much lower, remains in good condition thanks to the alkaline waters of Lake Van.

“Today, we are here to announce the discovery of a castle that has remained underwater in Lake Van,” videographer Tahsin Ceylan told Hurriyet Daily News.

“I believe that in addition to this castle, microbialites will make contributions to the region’s economy and tourism. It is a miracle to find this castle underwater. Archaeologists will come here to examine the castle’s history and provide information on it.”

Ceylan explained that the walls of the fortification cover an area of about one square kilometer (0.4 square miles).

About 3 to 4 meters (10 to 13 feet) of the wall are visible above the lake bed, but it is not clear how deep the walls go, so detailed excavations need to be carried out on the newly-discovered castle to learn more.

Mysterious Civilization

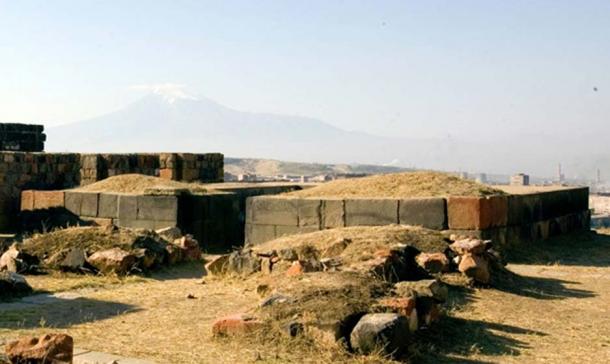

Archaeologists believe the castle was built by the Urartians, a mysterious civilization that existed in what is now Eastern Turkey, Iran, and the modern Armenian Republic, from around the 13th century BC.

Very little is known about the kingdom of Urartu and the origins of its people, but they spoke a language related to Hurrian, are well-known for their advanced metallurgy, and used an adapted form of the Assyrian cuneiform script.

Ceylan told Hurriyet Daily News that they named Lake Van the ‘upper sea’ and believed it had many mysterious secrets.

The fortification shows evidence of stones cut in a style used by the Urartians.

After a period of expansion, the Kingdom of Urartu came under attack starting around the 8th century BC. It was finally destroyed towards the end of the 6th century BC.

Many Armenians today claim that they are descendants of the Urartians.