Were Steel Tools Used in the Late Bronze Age?

A study by an international and interdisciplinary team headed by Freiburg archaeologist Dr. Ralph Araque Gonzalez from the Faculty of Humanities has shown that steel tools were already in use in Europe around 2900 years ago.

Using geochemical analyses, the researchers were able to prove that stone stelae on the Iberian peninsula that date back to the Final Bronze Age feature complex engravings that could only have been done using tempered steel.

This was backed up by metallographic analyses of an iron chisel from the same period and region (Rocha do Vigio, Portugal, ca. 900 BCE) that showed the necessary carbon content to be proper steel.

The result was also confirmed experimentally by undertaking trials with chisels made of various materials: only the chisel made of tempered steel was suitably capable of engraving the stone. Until recently it was assumed that it was not possible to produce suitable quality steel in the Early Iron Age and certainly not in the Final Bronze Age, and that it only came to be widespread in Europe under the Roman Empire.

“The chisel from Rocha do Vigio and the context where it was found show that iron metallurgy including the production and tempering of steel was probably indigenous developments of decentralized small communities in Iberia, and not due to the influence of later colonization processes. This also has consequences for the archaeological assessment of iron metallurgy and quartzite sculptures in other regions of the world,” explains Araque Gonzalez.

The study ‘Stone-working and the earliest steel in Iberia: Scientific analyses and experimental replications of final bronze age stelae and tools’ has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Iberian pillars of siliceous quartz sandstone could only be worked with tempered steel

The archaeological record of Late Bronze Age Iberia (c. 1300-800 BCE) is fragmentary in many parts of the Iberian Peninsula: sparse remains of the settlement and nearly no detectable burials are complemented by traces of metal hoarding and remains of mining activities.

Taking this into account, the western Iberian stelae with their depictions of anthropomorphic figures, animals, and selected objects are of unique importance for the investigation of this era.

Until now, studies of the actual rocks from which these stelae were made to gain insights into the use of materials and tools have been the exception. Araque Gonzalez and his colleagues analyzed the geological composition of the stelae in depth.

This led them to discover that a significant number of stelae were not as had been assumed made of quartzite, but silicate quartz sandstone. “Just like quartzite, this is an extremely hard rock that cannot be worked with bronze or stone tools, but only with tempered steel,” says Araque Gonzalez.

Chisel discovery and archaeological experiments confirm the use of steel

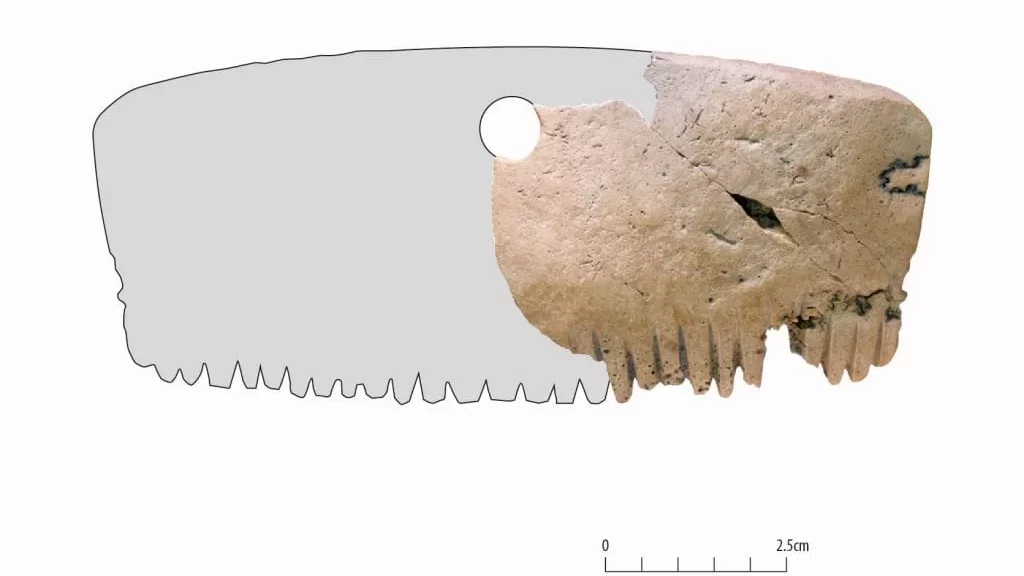

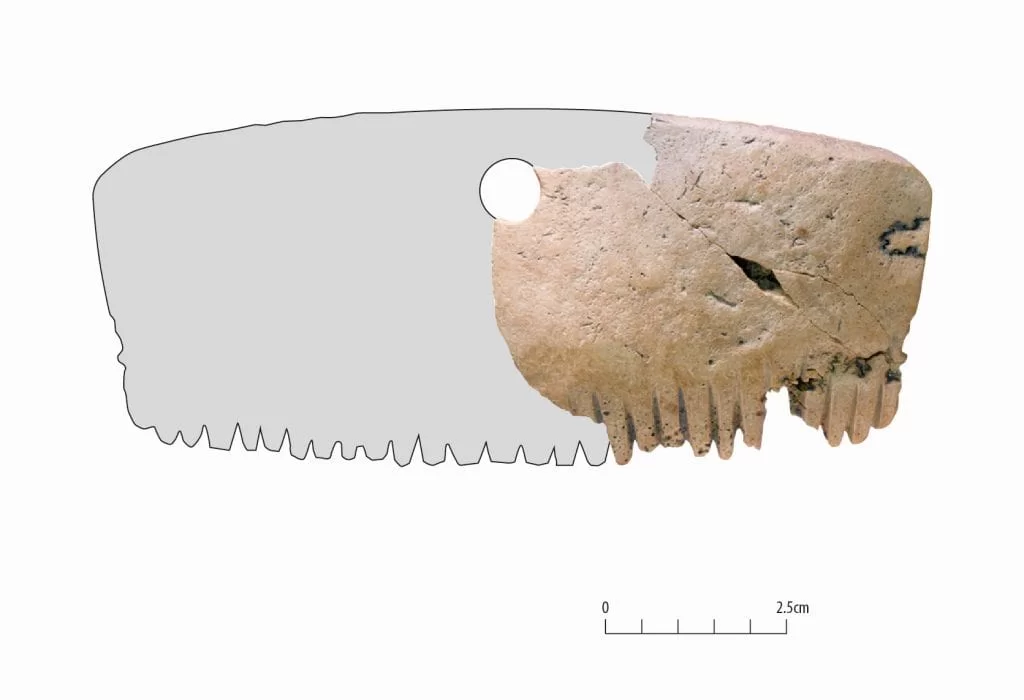

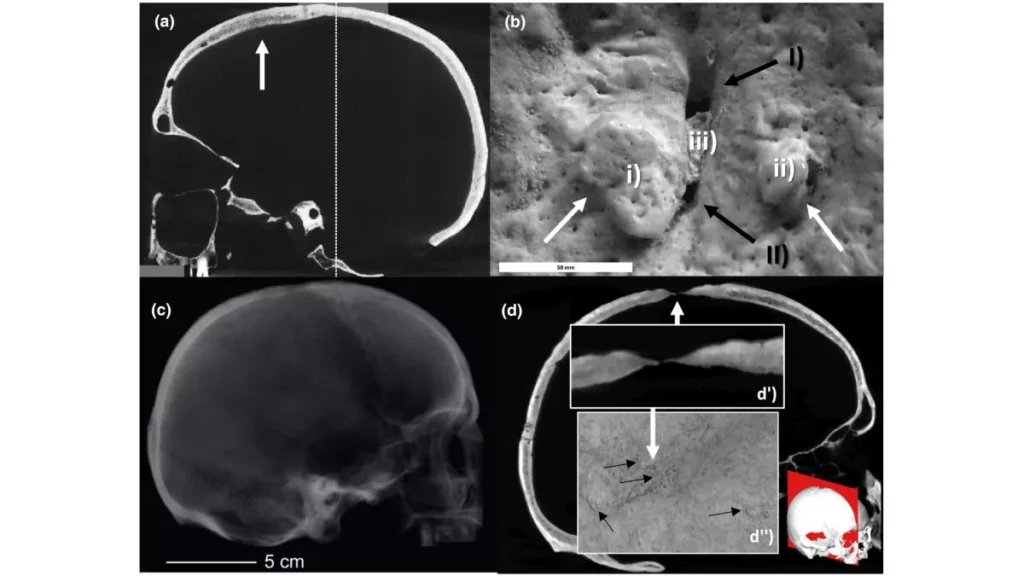

Analysis of an iron chisel found in Rocha do Vigio showed that Iberian stonemasons from the Final Bronze Age had the necessary tools.

The researchers discovered that it consisted of heterogeneous yet astonishingly carbon-rich steel. To confirm their findings, the researchers also carried out an experiment involving a professional stonemason, a blacksmith, and a bronze caster, and attempted to work the rock that the pillars were made of using chisels of different materials.

The stonemason could not work the stone with either the stone or the bronze chisels, or even using an iron chisel with an untempered point. “The people of the Final Bronze Age in Iberia were capable of tempering steel.

Otherwise, they would not have been able to work the pillars,” concludes Araque Gonzalez as a result of the experiment.