Why ancient Romans used sketchy, lopsided dice to gamble and play board games

People have been rolling dice for a long, long time. The first dice were made from sheep knucklebones more than 5,000 years ago in ancient Sumer, and you won if it landed on the right one of the four flat sides. Around 3,000 years ago, somebody from modern-day Iraq and Iran sculpted bits of wood and ivory into the familiar six-sided dice, with different numbers of spots on each side from one to six.

People all over the world adopted this configuration long before Arabic numerals were invented. But few people of the ancient world loved to play dice as much as the Romans did.

The Romans called their 6-sided dice tesserae, and they often used them to move the pieces on a game board or for gambling, with the highest number providing the win. Since hard cash was on the line, one would expect these dice to be “fair”, or equally likely to land on any of their six sides.

However, most of them were actually lopsided, with some sides obviously much larger than others, making them more likely to land on them. These Roman-era dice were a total mess when it came to their shape, with no two sides shaped entirely alike.

Why would the Romans make their dice so asymmetrical? It’s not like the builders of great aqueducts and roads weren’t capable of carving a uniform cube, after all.

At first glance, it would seem like tesserae was made this way as a form of cheating, in order to increase the probability of showing a certain side. The vast majority of Roman dice were biased towards the numbers one and six. However, this doesn’t explain why virtually all Roman dice were designed this way. Did all the players cheat? The games would have collapsed if that were the case, and people would stop using them if cheating was done on purpose. This all suggests that the lumpy and lopsided design is a feature, not a bug.

The die has been cast — and that is the will of the gods

In a new study, archaeologist Jelmer Eerkens, a professor of anthropology at the University of California Davis, and Alex de Voogt, a professor at the department of economics and business of Drew University in New Jersey, present a different perspective: the asymmetrical features of the dice were related to the way the ancient Romans viewed the role of fate and the gods in the world.

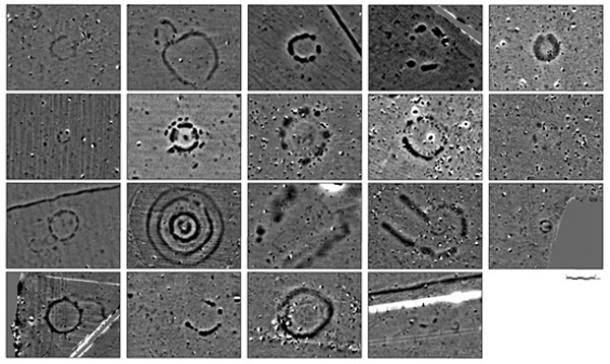

In a previous study, the two researchers showed that over 90% of Roman dice found in the archaeological record are visibly asymmetrical, meaning one of their sides differs in size from the others by at least 5%. In their new work, the pair of scientists analyzed a sample of 28 dice from the Roman era excavated in the Netherlands. Unsurprisingly, 24 of the 28 objects made from clay, metal, and bone were visibly asymmetrical.

The larger the difference in size between the six sides of a dice, the greater the odds of rolling the number opposite the side with the largest surface area. In a perfect cube, there should be a 1 in 6 chance of rolling any number, but the odds of landing on the largest side of a Roman dice could be as high as 1 in 2.4. Surely, these kinds of visible biases couldn’t have been missed, especially by the hardcore gamblers playing for hours at end in Rome’s slums.

To get a better understanding of what the ancient Romans were thinking when they made their lopsided dice, Eerkens and de Voogt enlisted 23 psychology majors for an experiment.

Like today, Roman dice were numbered in the ‘sevens’ configuration, meaning the pips (little holes or divots) on opposite sides to each other add up to the number 7, so 1 is opposite to 6, 2 is opposite to 5, and 3 is opposite to 4.

The students were handed reproductions of Roman dice and were asked to place pips on the sides. Other than having to respect the sevens configuration, the participants were given no further instructions and were virtually oblivious to the purpose of the experiment.

Most of the students placed the one and six pips on the largest opposing surfaces of the lopsided dice — that’s exactly how the Romans chose to number their dice. Since both ancient Romans and modern students with no interest in gambling placed pips in locations that favour a one or six suggests both groups involuntarily chose this configuration, rather than making a conscious effort to cheat and stack the odds in their favour.

When asked about what prompted them to place the pips the way they had, the students said it felt natural to place one and six on the largest sides, especially since six requires the most pips to place.

This experiment suggests that the Romans didn’t actually care that much for ‘fair’ odds, perhaps because they did not grasp the concept of probability. Instead, the ancient Romans put all their fate in the gods like Fortuna, the personification of luck. Since gods and fate played such a central role in the lives of these people, any side that rolled on the dice was the ‘right’ side — the one chosen by the gods. Of course, some experienced gamblers may have noticed the bias and used it to their advantage, but the unfair odds were likely not common knowledge at the time.

“Knowing that it makes sense that Romans probably did not think that die shape mattered because even with a non-cubic die all sides can still be thrown,” Eerkens told Haaretz. “Today we would say that, yes, each side can be thrown but with unequal probabilities – however, most people in Roman times probably would not understand that way of thinking.”

Such thinking may have persisted until well into the Middle Ages. It wasn’t until the Renaissance period that we start seeing perfectly fair cube-shaped dice, and it is perhaps no coincidence that around this time great thinkers like Galileo Galilei or Blaise Pascal were publishing papers about chance and probability, in some cases, they were actually consulting with local gamblers. These new ideas about fairness, chance, and mathematical probability may have spread among the ‘gamers’ of the time and finally led to fairer dice.

The new findings appeared in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.