Pictish Carved Stone Unearthed in Scotland

Archaeologists have uncovered a Pictish symbol stone close to the location of one of the most significant carved stone monuments ever uncovered in Scotland.

The team from the University of Aberdeen hit upon the 1.7metre-long stone in a farmer’s field while conducting geophysical surveys to try and build a greater understanding of the important Pictish landscape of Aberlemno, near Forfar.

Aberlemno is already well known for its Pictish heritage thanks to its collection of unique Pictish standing stones the most famous of which is a cross-slab thought to depict scenes from a battle of vital importance to the creation of what would become Scotland – the Battle of Nechtansmere.

The archaeologists were conducting geophysics surveys of the ground early in 2020 in an effort to better understand the history of the existing stones as part of the Leverhulme Trust-funded Comparative Kingship project.

Taking imaging equipment over the ground, they found anomalies that looked like evidence of a settlement. A small test pit was dug to try and establish whether the remains of any buildings might be present but to their surprise, the archaeologists came straight down onto a carved Pictish symbol stone, one of only around 200 known.

Their efforts to establish the character of the stone and settlement were hindered by subsequent Covid lockdowns and it was several months before they were able to return to verify their find.

The team think the stone dates to around the fifth or sixth century and, over the last few weeks, they have painstakingly excavated part of the settlement and removed it from its resting place – finding out more about the stone and its setting.

Professor Gordon Noble who leads the project says stumbling upon a stone as part of an archaeological dig is very unusual.

“Here at the University of Aberdeen we’ve been leading Pictish research for the last decade but none of us has ever found a symbol stone before,” he said.

“There are only around 200 of these monuments known. They are occasionally dug up by farmers ploughing fields or during the course of road building but by the time we get to analyse them, much of what surrounds them has already been disturbed.

“To come across something like this while digging one small test pit is absolutely remarkable and none of us could quite believe our luck.

To come across something like this while digging one small test pit is absolutely remarkable and none of us could quite believe our luck”

~Professor Gordon Noble.

“The benefits of making a find in this way are that we can do much more detailed work in regard to the context. We can examine and date the layers underneath it and extract much more detailed information without losing vital evidence.”

Research fellow Dr James O’Driscoll who initially discovered the stone describes the excitement: “We thought we’d just uncover a little bit more before we headed off for the day. We suddenly saw a symbol. There was lots of screaming. Then we found more symbols and there was more screaming and a little bit of crying!

“It’s a feeling that I’ll probably never have again on an archaeological site. It’s a find of that scale.”

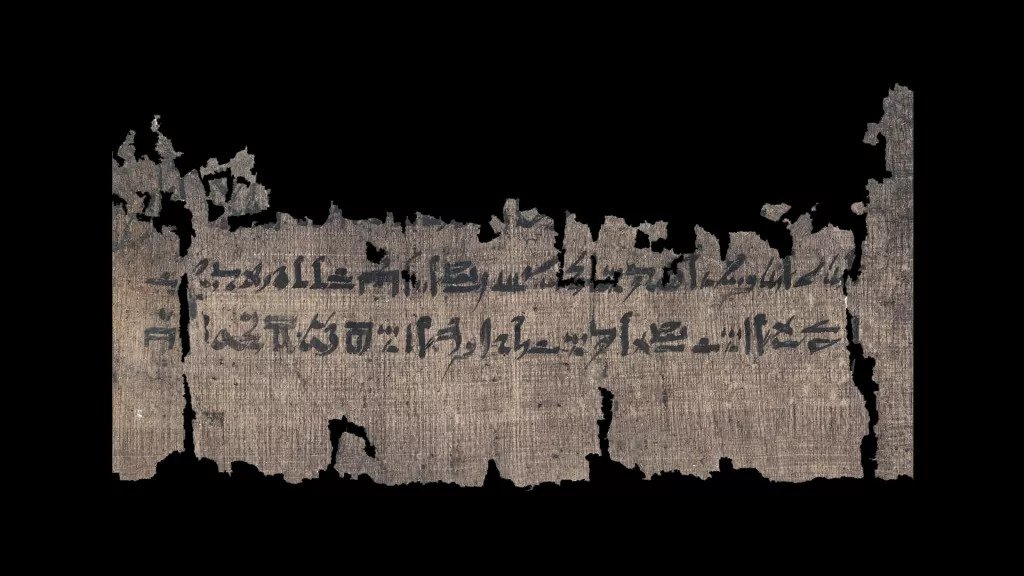

Like the other stones at Aberlemno, the new discovery appears to be intricately carved with evidence of classic abstract Pictish symbols including triple ovals, a comb and mirror, a crescent and V rod and double discs. Unusually the stone appears to show different periods of carving with symbols overlying one another.

The stone has now been moved to Graciela Ainsworth conservation lab in Edinburgh where a more detailed analysis will take place. Professor Noble hopes that it could make a significant contribution to understanding the significance of Aberlemno to the Picts.

“The stone was found built into the paving of a huge building from the 11th or 12th century. The paving included Pictish stones and examples of Bronze Age rock art. Excitingly the 11th-12th century building appears to be built directly on top of settlement layers extending back to the Pictish period” he added.

“The cross-slab that stands in the nearby church at Aberlemno has long been thought to depict King Bridei Mac Bili’s defeat of the Anglo Saxon King Ecgfrith in 685, which halted the expansion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to the north.

“The settlement of Dunnichen, from which the battle is thought to have taken its name, is just a few miles from Aberlemno. In recent years scholars have suggested another potential battle site in Strathspey, but the sheer number of Pictish stones from Aberlemno certainly suggests the Aberlemno environs was a hugely important landscape to the Picts.

“The discovery of this new Pictish symbol stone and evidence that this site was occupied over such a long period will offer new insights into this significant period in the history of Scotland as well as helping us to better understand how and why this part of Angus became a key Pictish landscape and latterly an integral part of the kingdoms of Alba and Scotland.”

The project has had help from Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service and the Pictish Arts Society to get the stone lifted and to the conservation lab, with radiocarbon dating funded by Historic Environment Scotland.

Bruce Mann, Aberdeenshire Council Archaeologist, said: “We have been providing a service to Angus Council for many years and I can say this is one of the most important discoveries made in the area in the last thirty years. To find prehistoric rock art re-used in the floor of this building would be exciting in its own right, but to have the Pictish symbol stone as well is just amazing.”

Researchers will now be working with the Pictish Arts Society to develop a fundraising campaign for the conservation and display of the stone.