Ancient Americans made art deep within the dark zones of caves throughout the Southeast

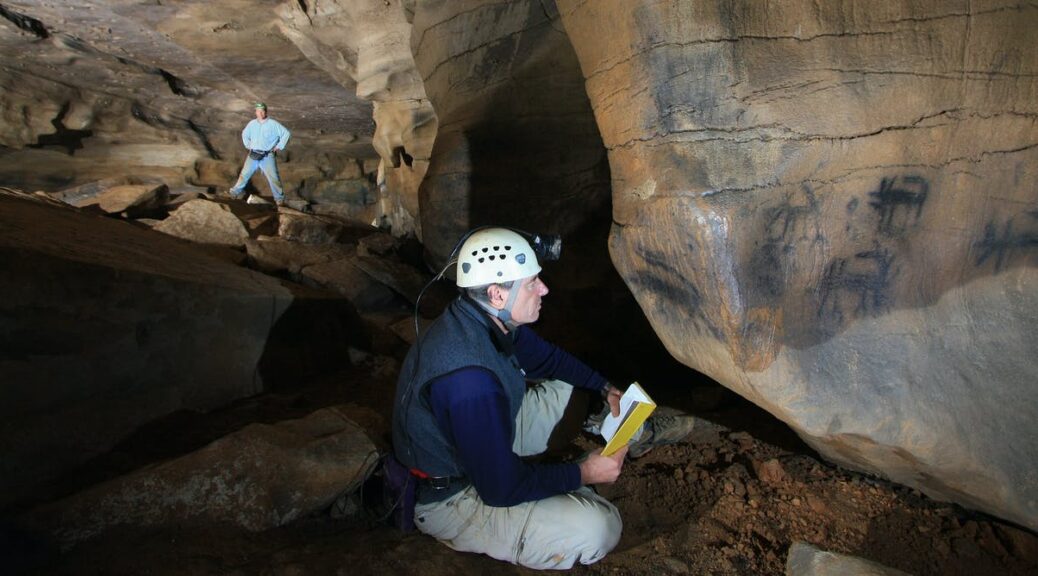

On a cold winter day in 1980, a group of recreational cavemen entered the course of a narrow, wet stream south of Knoxville, Tennessee. He navigated a slippery mud slope and a tight keyhole through the cave wall, trampled himself through the stream, sank through another keyhole and climbed more mud. Eventually, they entered a high and relatively dry passage deep in the “dark zone” of the cave – beyond the reach of outside light.

On the walls around them, they began to see lines and shapes in the remains of the soil laid long ago, when the stream flowed at this high level. No modern or historical graffiti intersected the surfaces. He saw images of animals, people and transformational characters with birds with human characteristics and mammals with snakes.

Ancient cave art has long been the most compelling of all artefacts from the human past, fascinating to both scientists and the public. Its visible manifestations resonate through the ages, as to speak to us from ancient times. And in 1980 this group of caves occurred at the first ancient cave art site in North America.

Since then archaeologists like me have discovered dozens of cave art sites in the southeast.

We have been able to learn details about when cave art first appeared in the region, when it was mostly produced and what it might be used for. We have also learned a great deal by working with the surviving descendants of cave art makers, the present-day Native American peoples of the Southeast, about what cave art means and how important it is to indigenous communities.

Cave Art in America?

Some people think of North America when they think of ancient cave art.

The world’s first modern discovery of cave art was made in Altamira, northern Spain, in 1879, a century before Tennessee cavers made their discovery. The scientific establishment of that day immediately denied the authenticity of the site. Later discoveries served to substantiate this and other ancient sites. As the earliest manifestations of human creativity, perhaps 40,000 years old, European Palaeolithic cave art is now justifiably famous around the world.

But similar cave art was not found anywhere in North America, although Native American rock art has been recorded outside the caves since the arrival of Europeans. The artefact deep beneath the ground was unknown in the 1980s, and the Southeast was an impossible place to find it, given how much archaeology had been done there since the colonial period.

Nevertheless, Tennessee cavers assumed they were seeing something extraordinary and brought archaeologist Charles Faulkner to the cave. He started a research project there, named Mud Glyph Cave. His archaeological works have shown that the art was from the Mississippian culture, about 800 years old, and depicts imagery characteristic of ancient Native American religious beliefs. Many of those beliefs are still held by descendants of Mississippian peoples: the modern Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Kaushatta, Muskogee, Seminole and Yuchi, among others.

Following the discovery of Mud Glyph Cave, archaeologists at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, began systematic cave surveys. Today, we’ve listed 92 dark-zone cave art sites in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. Some sites are also known in Arkansas, Missouri and Wisconsin.

What did he paint?

There are three forms of southeastern cave art.

- Mud glyphs, like Mud Glyphs Cave, are images found in soil surfaces preserved in caves.

- Petroglyphs are images carved directly into the limestone of the cave walls.

- Pictographs are paintings, usually made with charcoal-based pigments, that are placed on cave walls.

- Sometimes, more than one technique is found in the same cave, and neither method appears in other ways at an earlier or later time.

Some southeastern cave art is quite ancient. The oldest cave art sites date back to about 6,500 years, during the Archaic period (10,000–1000 BC). These early sites are rare and appear to be clustered on the modern Kentucky–Tennessee state line. The imagery was simple and often abstract, although representational images do exist.

The number of cave art sites increases with time. The Woodland period (1000 BC – 1000 AD) saw a more general and more widespread art production. Abstract art was still abundant and less mundane. Perhaps more spiritual subject matter was common. During the woodland, collisions between humans and animals such as “bird-man” made their first appearance.

The Mississippian period (AD 1000–1500) is the last contact stage in the Southeast before the arrival of Europeans, and it was when most dark-zone cave arts were produced. The theme is explicitly religious and includes spirit people and animals that do not exist in the natural world. There is also strong evidence that Mississippian art caves were compositions, in which images were arranged through cave passages to suggest stories or narratives in a systematic way, however, their locations and relationships were told.

Cave art continued into the modern era

In recent years, researchers have realized that cave art has a strong connection with the historical tribes that occupied the Southeast at the time of the European invasion.

In several caves in Alabama and Tennessee, inscriptions from the mid-19th century were inscribed on the cave walls in the Cherokee course. This writing system was invented by Cherokee scholar Sequoyah between 1800 and 1824 and was quickly adopted as the tribe’s primary means of written expression.

Cherokee archaeologists, historians, and linguists, along with non-native archaeologists like me, have documented and translated these cave writings. As it turns out, they refer to various important religious ceremonies and spiritual concepts that emphasize the sacred nature of the caves, their isolation and their connection to powerful spirits. These texts reflect similar religious ideas represented by graphic images in the earlier, pre-Contact time period.

Mud Glyph Cave was first discovered more than four decades ago, based on all the rediscoveries, the cave art in the Southeast for a long time. These artists worked in ancient times when ancestral Native Americans lived in the rich natural landscapes of the Southeast all the way through historical times, before forcibly removing indigenous people east of the Mississippi River in the 1830s. Trail of Tears was seen.

As the survey continues, researchers uncover more dark cave sites each year – in fact, four new caves were found in the first half of 2021. With each new discovery, the tradition began to reach the richness and diversity of the Palaeolithic art of Europe, where 350 sites are currently known. Archaeologists were unaware of the dark-zone cave art of the American Southeast even 40 years ago, indicating that new finds may be discovered in areas that have been explored for centuries.