Ancient mass grave, WWII bunker among new finds in Istanbul’s Haydarpaşa dig

The ongoing archaeological excavation on the premises of Istanbul’s iconic Haydarpaşa Train Station entered a new phase with the recent removal of concrete platforms, with ancient mass graves, a mausoleum and a bunker used during World War II joining a long list of artefacts retrieved from the area.

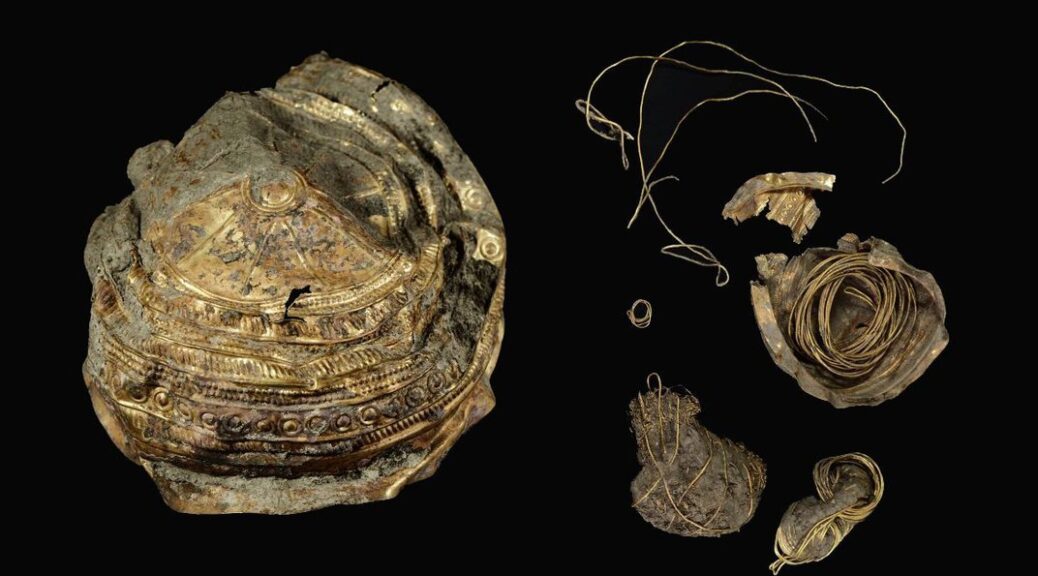

Precious historical artefacts dating back to the fifth century B.C. have been uncovered in the excavations that have been ongoing for the past three years in the 30-hectare (74-acre) facility housing platforms, maintenance wards, depots, parking lines and manoeuvre areas.

These artefacts shed light on the history of the 15-million megapolis and the Asian district of Kadıköy, where the ancient city of Chalcedon once stood.

Istanbul Archaeology Museum Director Rahmi Asal told reporters Sunday that the backyard of the station has indeed turned into an archaeological site. “The current area where we are working is inside the western harbour of Chalcedon. Indeed, very important ruins and artefacts were recovered. One of them is a private residence with opus sectile flooring dating back to the A.D. fifth century, along with a bathhouse,” Asal was quoted as saying by Anadolu Agency (AA).

“We also came across a section of Sainte Bassa Church, an important ruin from the Byzantine era that is narrated both in antique sources as well as modern publications. Inside the church’s apse, a mass grave was found containing approximately 28 bodies,” Asal said. Other findings include a platform dating back to the Hellenistic period, a pedestal probably belonging to a mausoleum and an adjacent sarcophagus, ruins from a holy spring (hagiasma in Greek, ayazma in Turkish) inside a palace ruin, and stone brick building dating back to the A.D. fifth to sixth centuries believed to be used as a melting workshop due to the furnaces and pots found there.

An Ottoman-era water fountain, erected in 1790 in connection with other fountains in nearby Halitağa Street and underwent repairs in 1836, was also uncovered at the site.

Another interesting finding covered by platforms was a 400-meter (1,312-foot) long bunker, which is 2 meters in width and 2.40 meters in height. Built-in 1942, the bunker also contains electrical panels and toilets.

Asal stated that nearly 12,000 gold, silver and bronze coins in good condition were retrieved from the excavation site, with the most important being a coin dating back to the fifth century B.C.

Explaining that the excavation went down some 2 meters in parts, Asal said that an interrupted chronological settlement from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman periods can be traced on all layers of the earth. “If we were to talk about the history of Kadıköy in particular, our information on its archaeology and art history was unfortunately scarce apart from information in antique sources. We can say that these excavations are rewriting, reshaping the history of Kadıköy with concrete archaeological documents.”

Asal explained that the excavation is ongoing as part of the Haydarpaşa restoration project of the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure, and it is not possible to give an exact time frame on when the excavation will end since it depends on both the project requirements and new archaeological findings shaping it.

“We know that currently, a new project is in the making that also utilizes recovered artefacts and adds them into the station project. Once we see that project, like the museum, we will convey our excavation results and assessment report to the local conservation board, which will shape the remaining process accordingly.”

The priority of archaeologists, art historians and citizens should be the Haydarpaşa Station itself, Asal said, underlining that the symbolic landmark should preserve its primary function as a terminus station and archaeological findings should be integrated into that function.

Yalçın Eyigün, head of the General Directorate of Infrastructure of the Transport and Infrastructure Ministry, told Demirören News Agency (DHA) that the designing process for closed areas and an open-air museum is ongoing, which the ministry seeks to complete in the next two years.

Currently, work has been completed on 49% of the 140,000 square meters area slated for excavations, Eyigün said, adding that 250 staff are working under the supervision of 15 archaeologists and the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Explaining that the total area of the Haydarpaşa compound is 4.75 hectares, Eyigün said the ministry aims to use only 75,000 square meters for railroad-related activities, with the rest allocated for an archaeological site, archaeological park and an industrial heritage museum.

The area, formerly known as Haydarpaşa Meadows before railway construction began in 1872, has many well-preserved or intact artefacts, due to the fact that construction began later than in the rest of Istanbul’s central neighbourhoods. The station building itself, which was constructed between 1906 and 1909, sits atop 1,100 wooden piles on reclaimed land.

Once serving as the western terminus of the Ottoman Empire’s ambitious Hejaz and Baghdad railways, the station has been closed to passengers since June 2013 when suburban rail services stretching to the Gebze district of Kocaeli province were halted for the Marmaray project. Featuring a submerged train tunnel crossing the Bosporus and revamping the old suburban rail lines to increase train and passenger capacity, the Marmaray bypasses Haydarpaşa and its European counterpart, the Sirkeci Station. Intercity trains to Anatolia were also scrapped a year earlier over the ongoing construction for a high-speed train.

The station experienced several setbacks throughout its history. On the first day of its opening in 1908, a fire broke out and it was reopened on Nov. 4, 1909, after a restoration process. The station housed an armoury and ammunition depot during World War I but was damaged on Sept. 6, 1917, when the armoury exploded. The station completely collapsed after that. On the 10th anniversary of the founding of the Turkish republic, the station was rebuilt to its original state and a comprehensive restoration was also carried out in 1976.

In 1979, certain sections of the station were damaged during the Independent tanker accident, in which a Romanian crude oil carrier exploded after colliding with a Greek freighter on the Bosporus off Haydarpaşa Port.

Following a 2010 fire that broke out during repairs, a temporary protective roof was placed to protect the building from rainfall and snow. Several projects were made public over the years to reassess the building’s use as a hotel with a larger convention centre project in the surrounding rail facilities. Following calls from the public, the Turkish State Railways (TCDD) prepared a thorough restoration project for the building so it can serve its original function in 2016, which was approved by relevant authorities. The recent archaeological excavation began during repairs to tracks and platforms leading to the main station building.