What if We Aren’t the First Advanced Civilization on Earth?

Earth scientists at the turn of the century, Gavin Schmidt among them, were enthralled by a 56-million-year-old segment of geologic history known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). What most intrigued them was its resemblance to our own time: Carbon levels spiked, temperatures soared, ecosystems toppled. At professional workshops, experts tried to guess what natural processes could have triggered such severe global warming. At the dinner parties that followed, they indulged in less conventional speculation.

During one such affair, Schmidt, now the director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, couldn’t resist the comparison. If modern climate change — unambiguously the product of human industry — and the PETM are so alike, he mused, “Wouldn’t it be funny if it was the same cause?” His colleagues were charmed by the implication. An ancient race of intelligent, fossil-fueled… chickens? Lemurs? “But,” he says, “nobody took it seriously, obviously.” Until, nearly two decades later, he took it seriously himself.

One day in 2017, Schmidt received a visit from Adam Frank, a University of Rochester astrophysicist seeking insight into whether civilizations on other planets would inevitably alter their climates as we have. Truth be told, Frank expected his alien conjecture to come across as mildly outlandish.

He was surprised when Schmidt interrupted with an even stranger idea, one he’d been incubating for years: “What makes you so sure we’re the first civilization on this planet?”

Worlds Within

One thing nearly all human creations have in common is that geologically speaking, they’ll be gone in no time. Pyramids, pavement, temples and toasters — eroding away, soon to be buried and ground to dust beneath shifting tectonic plates. The oldest expansive patch of the surface is the Negev Desert in southern Israel, and it dates back a mere 1.8 million years. Once we disappear, it won’t take Earth long to scrub out the facade human civilization has built upon its surface. And the fossil record is so sporadic that a species as short-lived as us (at least so far) might never find a place in it.

How, then, would observers in the distant future know we were here? If the direct evidence of our existence is bound for oblivion, will anything remain to tip them off? It’s a short step from these tantalizing questions to the one Schmidt posed to Frank: What if we are the future observers, discounting some prehistoric predecessor that ruled the world in long, long ago?

Frank’s mind whirled as he considered. A devotee of the cosmos, he felt suddenly dazed by the mind-boggling immensity of what lay beneath, rather than above, him. “You’re looking at Earth’s past as if it were another world,” he says. At first glance, the answer seems self-evident — surely we would know if another species had colonized the globe like Homo sapiens did. Or, he now wondered, would we?

Take the analogy where the planet’s entire history is compressed into a single day: Complex life emerged about three hours ago; the industrial era has lasted only a few thousandths of a second. Given how rapidly we are rendering our home uninhabitable, some researchers think the average lifespan of advanced civilizations may be just a handful of centuries. If that’s true, the past few hundred million years could hide any number of industrial periods.

Humanity’s Technosignature

In the months after that conversation, Frank and Schmidt crafted what seems to be the first thorough scholarly response to the possibility of a pre-human civilization on Earth. Even sci-fi has mostly neglected the idea. One 1970s episode of Doctor Who, however, stars intelligent reptilians, awakened by nuclear testing after 400 million years of hibernation. In homage to those fictional forebears, the scientists dubbed their thought experiment the “Silurian hypothesis.”

Both scientists are quick to explain that they don’t actually believe in the hypothesis. There isn’t the slightest evidence for it. The point, as Frank puts it, is that “the question is an important one, and deserves to be answered with acuity,” not dismissed out of hand. Moreover, he says, “you can’t know until you look, and you can’t look until you know what to look for.” To see what traces an industrial civilization might leave behind, they start with the only one we’re aware of.

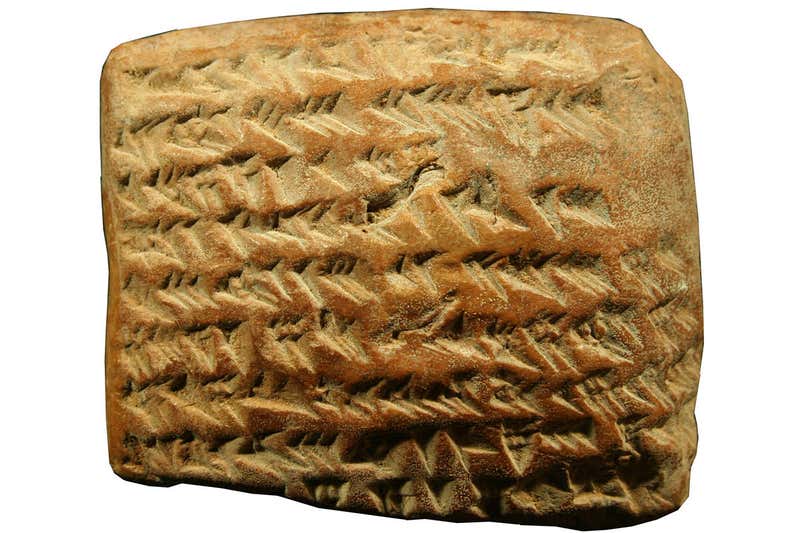

Our seemingly indelible mark on this planet will someday be reduced to a thin layer of rock, composed of the eclectic materials with which we’ve constructed the human world. Collectively they will make up our “technosignature,” the unique imprint that accompanies every technological species. For example, the sediment from our current geological epoch, the Anthropocene, will likely contain abnormal amounts of nitrogen from fertilizer, and rare-earth elements from electronics. Even more telling, it may harbor veins of substances that don’t occur naturally, like chlorofluorocarbons, plastics and manufactured steroids. (In fact, that’s the premise of an ominous short story Schmidt wrote to accompany the study.)

Of course, there’s no reason every civilization must unfold in the same way. Some may never avail themselves of plastic. But they must share certain universal features. Probably they would disperse indicator species, like mice and rats in our case, in their travels. And Schmidt notes that even aliens can’t violate the laws of physics: “Does every technological species need energy? Yes, so where does the energy come from?”

We humans conquered our planet with the help of combustion, and it seems reasonable to bet that ascendant life forms everywhere do the same. It’s just intuitive, Frank says: “There’s always biomass, and you can always set biomass on fire.” For a long time we’ve founded our industry on fossil fuels, and, climatic consequences aside, that will leave a geological footprint. Carbon occurs in three types, called isotopes. When we burn the tissues of long-dead creatures, we change the ratio of isotopes in the atmosphere, a shift known as the Suess effect. Scientists have noted similar ratios in events like the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, and if anyone is looking in another 50 million years, they should have no trouble seeing it in the Anthropocene.

Anyone Out There?

So what about the PETM? Did those fumes originate in the engines of primeval jalopies? Unlikely. The carbon surge of that period was far more gradual than the one that began with our Industrial Revolution. The same is true of other comparable events in the distant past; geologists have yet to find anything as abrupt as the Anthropocene. That said, the brevity may be the problem — it can be incredibly difficult to make out short intervals in the rock record, as well as at the astronomical level. Which brings us to the Fermi paradox.

If the universe is so vast, with so many livable planets, why haven’t we found any hint of intelligent life? That’s what puzzled the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. One solution is that plenty of civilizations have arisen, but they fizzle out so quickly that few exist at any given moment. Time, like space, is enormous, and humans may not overlap with many other extraterrestrial world-builders, reducing our chance of discovering any. Then there’s a more optimistic scenario: They may evade our notice not because they died off but because they mastered the art of sustainability, making their technosignatures less conspicuous.

That said, Frank is skeptical that a technological species could ever become undetectable — subtle, certainly, but not invisible. To build solar panels, you need raw materials; to acquire those materials, you need some other form of energy. As for wind power, recent research suggests that even if we raised enough turbines to power the planet, they too would contribute to short-term warming. This, Frank says, demonstrates at global scale the principle that there is no free lunch: “You cannot build a world-girdling civilization and not get some kind of feedback.”

The Search (and Fight) For Life

Since publishing the Silurian hypothesis, the authors have predictably attracted as many eccentrics as academics. “Everybody and their dog who has an ancient aliens podcast wanted to interview us,” Schmidt says. Both Schmidt and Frank realize the prospect of earlier earthlings is a seductive one. But regardless of who latches onto their hypothesis, they still see meaningful scientific lessons in their research.

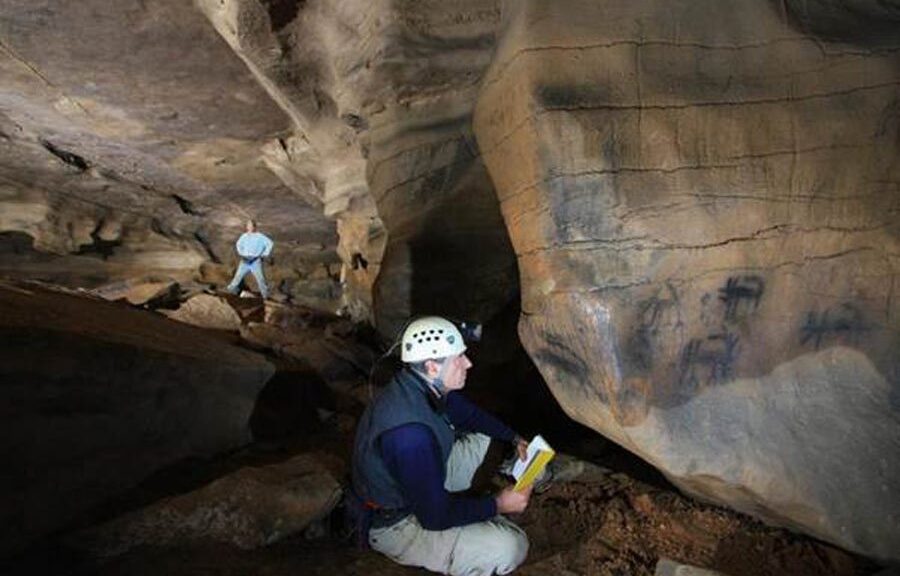

For one, they hope it will inspire geologists looking in (and astrobiologists looking out) to hone their methods of detection. To identify a bygone civilization, they argue, scientists must search for a broad range of signals at once, everything from carbon fluctuations to synthetic chemicals. And they’ll need to pinpoint the rise and fall of these signals, given the importance of timing in distinguishing natural and industrial causes.

The hypothesis also bears on the famous Drake equation, used for calculating the number of active civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy. The equation assumes at most one civilization per inhabitable planet; an increase in that estimate could radically change its output or the probability that we have intelligent galactic neighbours.

Perhaps most importantly, Frank and Schmidt’s work represents a call to action and humility. It could be that both potential solutions to the Fermi paradox — extinction and technological transcendence — are possible. If so, we have a choice: “Are we going to live sustainably, or are we going to keep making a mess?” Schmidt wonders. “The louder we are in the cosmos, the more temporary we’re going to be.” Through one door, humans achieve a lasting place in the universe. Through the other we exit, leaving only a trail of cataclysmic breadcrumbs as a warning for the next big-brained saps to find — or overlook.