1,600-Year-Old Sheep Mummy from Iran Analyzed

A team of geneticists and archaeologists from Ireland, France, Iran, Germany, and Austria has sequenced the DNA from a 1,600-year-old sheep mummy from an ancient Iranian salt mine, Chehrabad.

This remarkable specimen has revealed sheep husbandry practices of the ancient Near East and underlined how natural mummification can affect DNA degradation. The incredible findings have just been published in the international, peer-reviewed journal Biology Letters.

The salt mine of Chehrabad is known to preserve biological material. Indeed, it is in this mine that human remains of the famed “Salt Men” were recovered, dessicated by the salt-rich environment.

The new research confirms that this natural mummification process – where water is removed from a corpse, preserving soft tissues that would otherwise be degraded – also conserved animal remains.

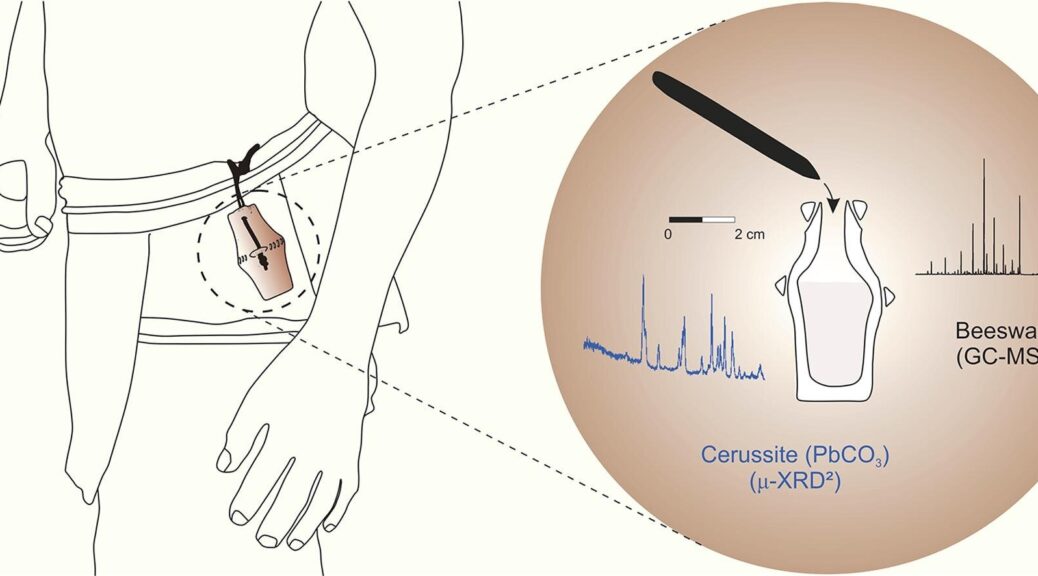

The research team, led by geneticists from Trinity, exploited this by extracting DNA from a small cutting of mummified skin from a leg recovered in the mine.

While ancient DNA is usually damaged and fragmented, the team found that the sheep mummy DNA was extremely well-preserved; with longer fragment lengths and less damage that would usually be associated with such an ancient age.

The group attributes this to the mummification process, with the salt mine providing conditions ideal for preservation of animal tissues and DNA.

The salt mine’s influence was also seen in the microorganisms present in the sheep leg skin. Salt-loving archaea and bacteria dominated the microbial profile – also known as the metagenome – and may have also contributed to the preservation of the tissue.

The mummified animal was genetically similar to modern sheep breeds from the region, which suggests that there has been a continuity of ancestry of sheep in Iran since at least 1,600 years ago.

The team also exploited the sheep’s DNA preservation to investigate genes associated with a woolly fleece and a fat-tail – two important economic traits in sheep. Some wild sheep – the asiatic mouflon – are characterised by a “hairy” coat, much different to the woolly coats seen in many domestic sheep today. Fat-tailed sheep are also common in Asia and Africa, where they are valued in cooking, and where they may be well-adapted to arid climates.

The team built a genetic impression of the sheep and discovered that the mummy lacked the gene variant associated with a woolly coat, while fibre analysis using Scanning Electron Microscopy found the microscopic details of the hair fibres consistent with hairy or mixed coat breeds.

Intriguingly, the mummy carried genetic variants associated with fat-tailed breeds, suggesting the sheep was similar to the hairy-coated, fat-tailed sheep seen in Iran today.

“Mummified remains are quite rare so little empirical evidence was known about the survival of ancient DNA in these tissues prior to this study,” says Conor Rossi, PhD candidate in Trinity’s School of Genetics and Microbiology, and the lead author of the paper.

“The astounding integrity of the DNA was not like anything we had encountered from ancient bones and teeth before.

This DNA preservation, coupled with the unique metagenomic profile, is an indication of how fundamental the environment is to tissue and DNA decay dynamics.

Dr Kevin G Daly, also from Trinity’s School of Genetics and Microbiology, supervised the study. He added:

“Using a combination of genetic and microscopic approaches, our team managed to create a genetic picture of what sheep breeds in Iran 1,600 years ago may have looked like and how they may have been used.

“Using cross-disciplinary approaches we can learn about what ancient cultures valued in animals, and this study shows us that the people of Sasanian-era Iran may have managed flocks of sheep specialised for meat consumption, suggesting well developed husbandry practices.“