Till death do us part! 3500-year-old tombs with hand-holding couples found

Russian scientists are trying to uncover the secrets of 3,500-year-old Bronze Age graves, where couples are buried together in a seemingly loving embrace – under suspicions of macabre explanation.

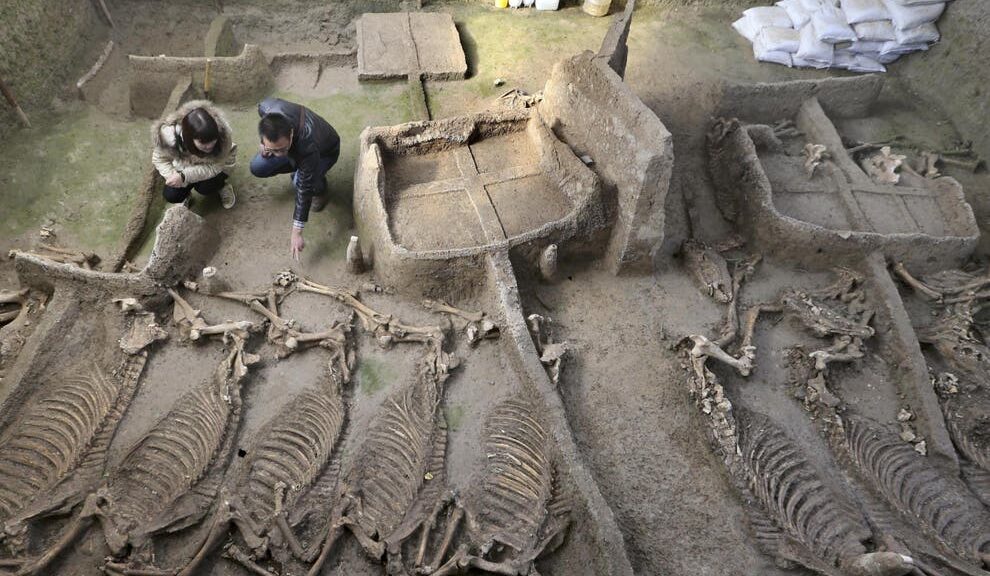

These pictures show ancient burials in the village of Staryi Tartas in Siberia where some 600 tombs were examined by experts.

Dozens contain the bones of couples, some with male and female skeletons, facing each other and their hands appear to be held together forever.

The Siberian Times said: ‘Archeologists are struggling for explanation and hope that DNA testing can provide answers for these remarkable burials.’ One writer, Vasiliy Labetskiy, described the scenes in the graves poignantly as skeletons in ‘post-mortal hugs with bony hands clasped together.

One theory is that these Andronovo burials show the start of the nuclear family, but another version that after the man died, his wife was killed and buried with him.

Still, another suggests that some of the couples were deliberately buried as if in a sexual act, possibly with a young woman sacrificed to play this role in the grave. Other graves at the site in the Novosibirsk region in western Siberia show adults buried with children.

Professor Vyacheslav Molodin, director of research of the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said: ‘We can fantasise a lot about all this.

‘We can allege that husband died and the wife was killed to be interred with him as we see in some Scythian burials, or maybe the grave stood open for some time and they buried the other person or persons later, or maybe it was really simultaneous death.

‘When we speak about a child and an adult, it looks more natural and understandable.

‘When we speak about two adults – it is not so obvious. So we can raise quite a variety of hypotheses, but how it was in fact, we do not know yet.’

Work is underway to establish the ‘kinship’ of these ancient couple burials using DNA research.

‘For example, we found the burial of a man and a child. What is the degree of their kinship? Are they father and son or…? The same question arises when we found a woman and a child. It should seem obvious – she is the mother. But it may not be so. She could be an aunt or not a relative at all. To speak about this scientifically we need the tools of paleogenetics.

‘We have a joint laboratory with the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Science, and we actively work in this direction. We do such analysis but it is quite expensive still and there are few specialists. We are also solving other questions with help of paleogenetics.’

With such couple burials, Professor Lev Klein, of St Petersburg State University, has proposed they are linked to reincarnation beliefs possibly influenced by Deeksha rituals in the ancient Indian sub-continent at the time when the oldest scriptures of Hinduism were composed.

‘The man during his lifetime donated his body as a sacrifice to all the gods,’ he wrote. ‘The ‘Deeksha was considered as a “second birth” and to complete this ritual the sacrificing one made a ritual sexual act of conceiving.’ In other words, in death, a man should perform a sexual act to impregnate a woman.

‘Perhaps in the pre-Vedic period relatives of the deceased often sought to reproduce the “Deeksha” posthumously, and sacrificed a woman or a girl (or a few), and simulated sexual intercourse in the grave,’ he said.

Professor Molodin doesn’t rule out this version, yet makes clear it is only a hypothesis that needs more study.

‘It is again a suggestion. As a suggestion, it could be. This idea of Klein can be extended to Siberia too because a significant part of the researchers think that Andronovo people were Iranians.

‘So this hypothesis can be extended to them. But, I will repeat, it is only a hypothesis.’