Roman Bath Discovered in Swiss Spa Town

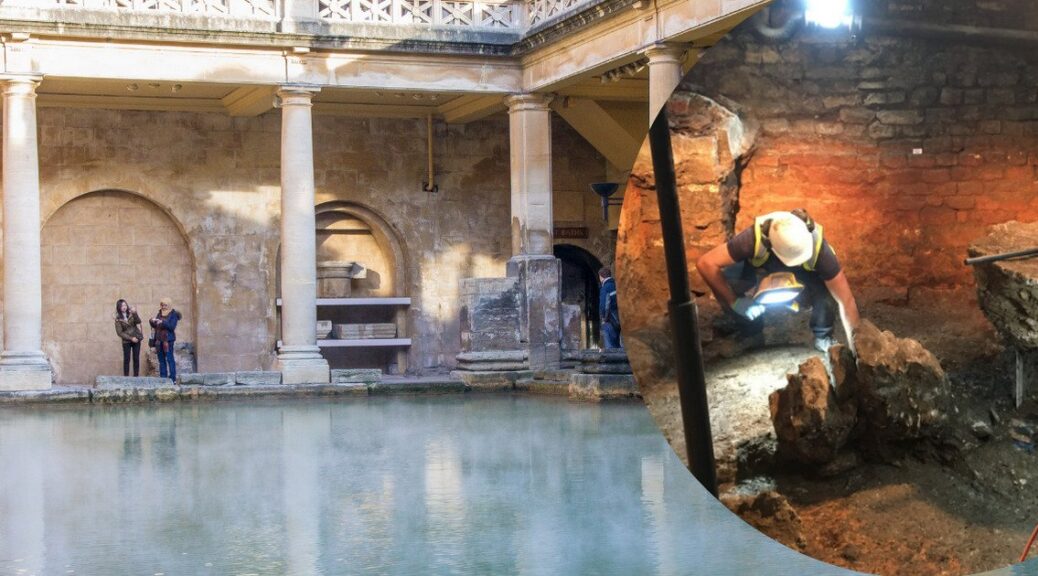

In the Swiss city of Baden, a Roman bath part of an ancient spa has been uncovered. It was dismantled at the new pipeline in Baden’s Kurplatz city center and in extremely good condition, completed with finely designed entry steps.

It dates back to the second half of the 1st or early 2nd century, according to archeologists. It was connected to a much later concrete conduit that piped the water from the thermal springs to the reservoir.

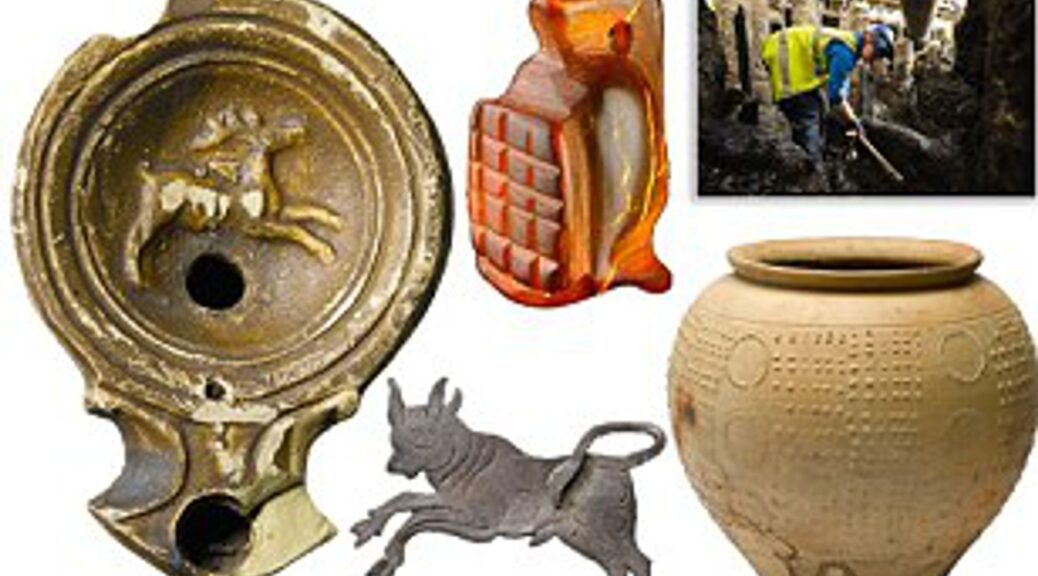

After finding a hot spring on the left bank of the Limmat river a few kilometers far off from the legionary settlement of the Vindonissa (modern day Windisch), Baden was founded by Romans as Aquae Helveticae about 20 A.D.

A civilian settlement grew around the mineral baths. It was burned by the legions during the upheavals of the Year of the Four Emperors (69 A.D.) but was quickly rebuilt in stone this time. The basin dates to the time of that reconstruction.

The highly mineralized waters always at a comfortable 47° C (117° F) combined with its riverbank location and a short distance from Zurich (less than 15 miles) made Aquae Helveticae a popular and easily accessible destination throughout the Roman period and beyond.

Even during times of decline, like when the troops left Vindonissa in the early 2nd century, the Roman baths were in continuous operation. In the 4th century, a defensive wall was built to protect the baths after the onslaught of Germanic incursions in the mid-3rd century.

While there is no surviving documentation of the use of the thermal baths after the collapse of the empire, but archaeological evidence does suggest at least some of the Roman facilities remained in operation through the 9th century.

By the 13th century, Aquae Helveticae had been rebuilt with new bathing facilities and a new name: Baden, the Middle German word for baths.

Most of the ancient Roman city and bath facilities lie under the modern spa town.

The remains of three bathing basins and few structures confirm that the medieval thermal baths and the modern ones were built over the Roman site and within its perimeters.

With so little material to go by, the question of whether the Roman bathing infrastructure was in continuous use after the Fall is still an open one.

The newly-discovered basin is a key clue, especially with the conduit pointing to it having been used after the late medieval reconstruction of Baden.

The basin is thought to be part of Baden’s legendary open-air St Verena Baths that were used from the Middle Ages well into the 19th century. But the find was probably only used early on, and at some point during its history, the St Verena Baths were made smaller and the Roman bath was forgotten, archaeologists believe.

But it remains important for the town’s spa history because it may provide a clue to whether there was continuous use of the baths between Roman and Medieval times, which has not yet been proven.

“We are very happy that we have further evidence of a 2,000-year-old bathing history [in Baden],” added [Andrea] Schaer, who is leading the archaeological project.

Also found was the structure that captured the spring water, which was built in the Middle Ages, but directly on the original Roman structure.