A 1,000-year-old wall in Peru was built to protect against El Niño floods, research suggests

An ancient desert wall in northern Peru was built to protect precious farmlands and canals from the ravages of El Niño floods, according to new research.

Many archaeologists had suggested that the wall, known as the Muralla La Cumbre and located near Trujillo, was built by the Chimú people to protect their lands from invasions by the Incas, with whom they had a long-standing enmity. But the latest research affirms a theory that the earthen wall, which stretches 6 miles (10 kilometers) across the desert, was built to hold back devastating floods during the wettest phases of northern Peru’s weather cycle.

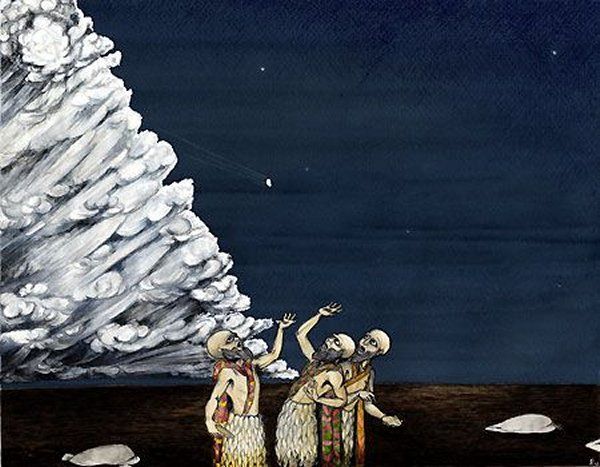

These phases are now known as El Niño — Spanish for “The Boy,” a reference to the child Jesus — because they bring heavy rain to the region around Christmastime every few years.

Although El Niño brings drought to some other parts of the world, it brings heavy rains to Ecuador and northern Peru. El Niño floods are thought to have occurred there for thousands of years, and they would have been a serious danger to the Chimú, Gabriel Prieto, an archaeologist at the University of Florida, told Live Science.

“The annual rainfall there in a regular year is very low — almost no rain at all,” he said. “So when the rainfall was very high, that caused a lot of damage.”

Ancient kingdom

The Chimor kingdom of the Chimú people emerged around A.D. 900 in the territories once occupied by the Moche people; as a result, the Moche period is sometimes called “Early Chimú.”

According to the “Encyclopedia of Prehistory” (Springer, 2002) the Chimú worshipped the moon — instead of the sun at the center of Inca worship — and they were independent until they were conquered by the Incas in about 1470, a few decades before the arrival of the Spanish in South America.

Today, the Chimú are known mainly for their distinctive pottery and metalwork, as well as for the ruins of their capital, Chan Chan, which are listed by the United Nations as a World Heritage site.

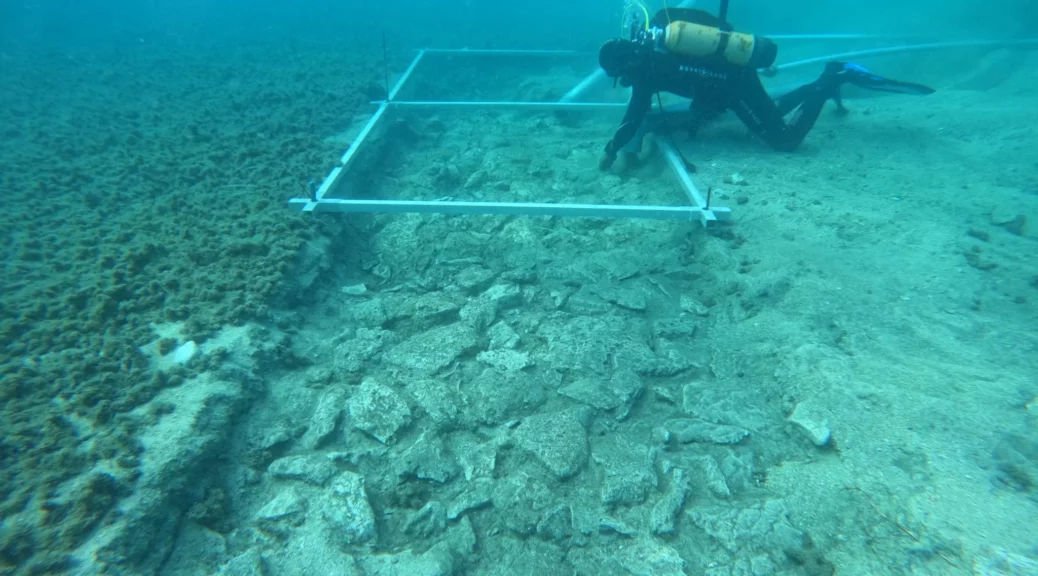

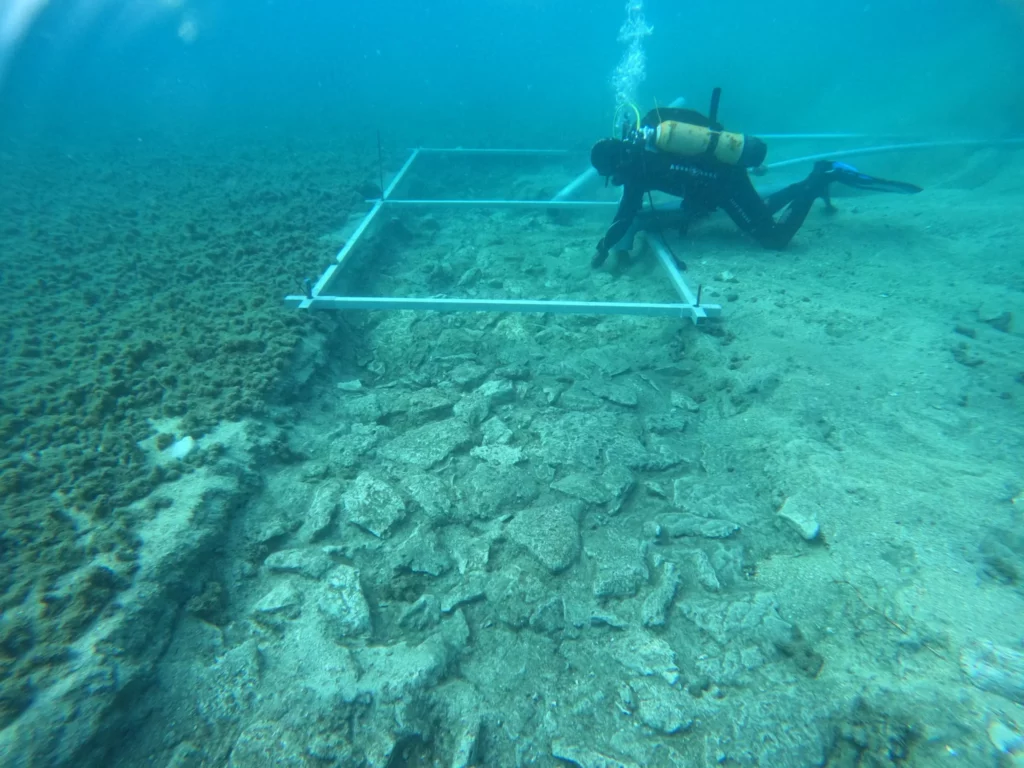

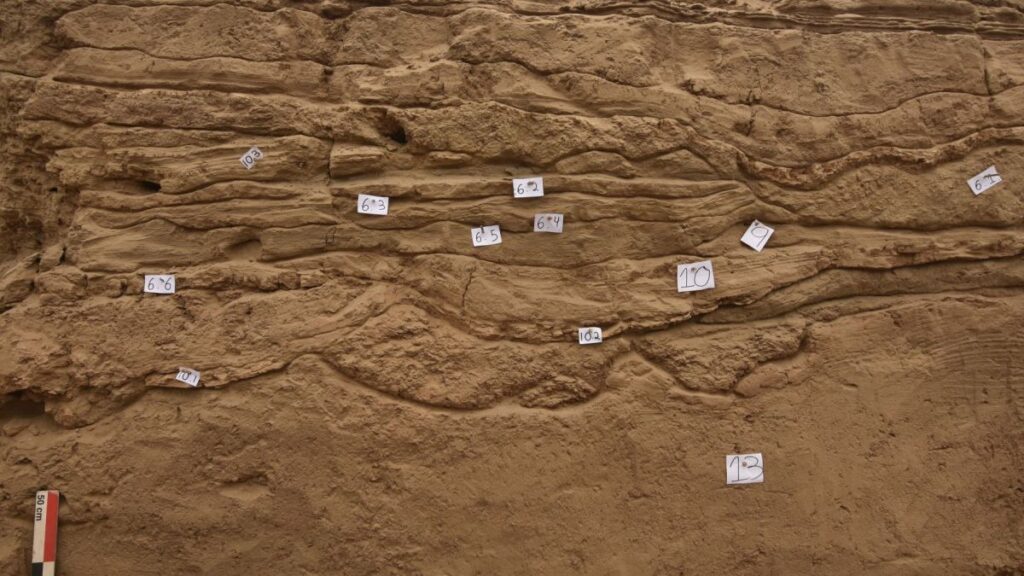

Prieto has examined the 8-foot-high (2.5 meters) La Cumbre wall and found layers of flood sediments only on its eastern side, which suggests it was built to protect the Chimú farmlands to the west, beside the coast. Radiocarbon dates from the lowest layers reveal that the wall was started in about 1100, possibly after a large El Niño flood at that time, he said.

The wall is built across two dry riverbeds that flood during El Niño. Preventing flooding in the farmlands also would have protected Chan Chan, which was connected to them by a network of canals.

“I’d guess, to some degree, that the wall worked like a kind of a dam,” Prieto said. The research has not yet been published as a peer-reviewed study.

Human sacrifices

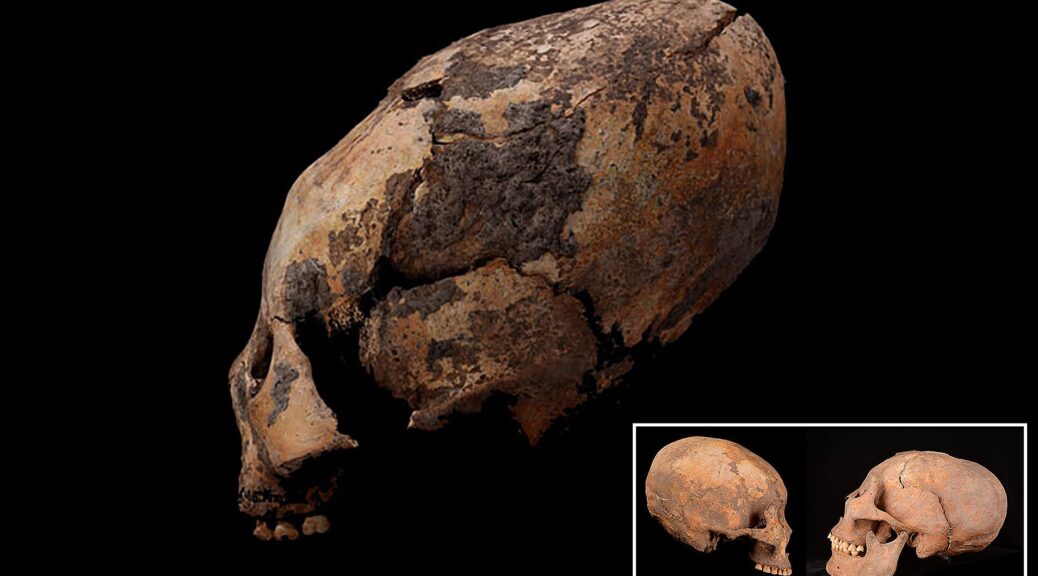

Prieto previously found evidence of mass child sacrifices at Chimú sites, including the remains of 76 victims at Pampa La Cruz near Huanchaco, a few miles northwest of Trujillo. He thinks the El Niño floods that necessitated the desert wall also may have been linked to the sacrifices.

Prieto has used radiocarbon dating to determine that one of the sediment layers along the wall is from about 1450 — a date that corresponds to the sacrifice of more than 140 children and 200 llamas at another Chimú site. He thinks it’s likely that the Chimú knew the dangers of El Niño floods, which happened every few years, and that their society’s rulers took advantage of the recurring disaster to solidify their authority with sacrifices.

“The Chimú were the descendants of people who had lived in this region for 10,000 years — they knew exactly what was going on,” he said. “This was a kind of political game, I think.”

Edward Swenson, an archaeologist at the University of Toronto who isn’t involved in the research, told Live Science that Prieto’s interpretation made sense.

“The idea at first struck me as incongruous because I’ve not heard of walls against water before,” he said.

But Prieto’s research has changed his mind, although he still thinks the wall also may have served as a defense. “The old idea was that this wall was to protect the Chimú from Inca attacks, and it might have been multifunctional,” Swenson said.