Evidence of Egypt’s Great Revolt Uncovered

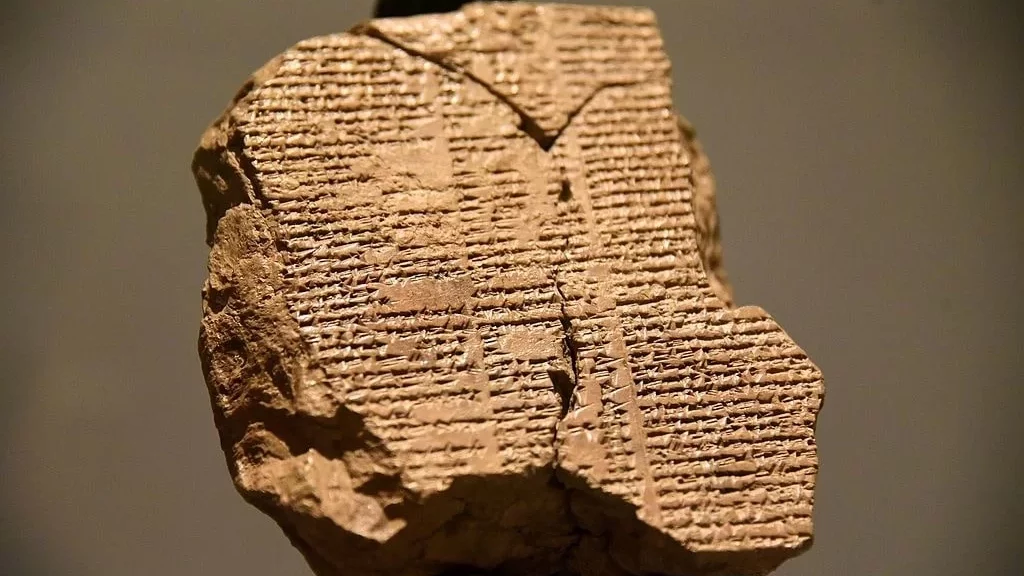

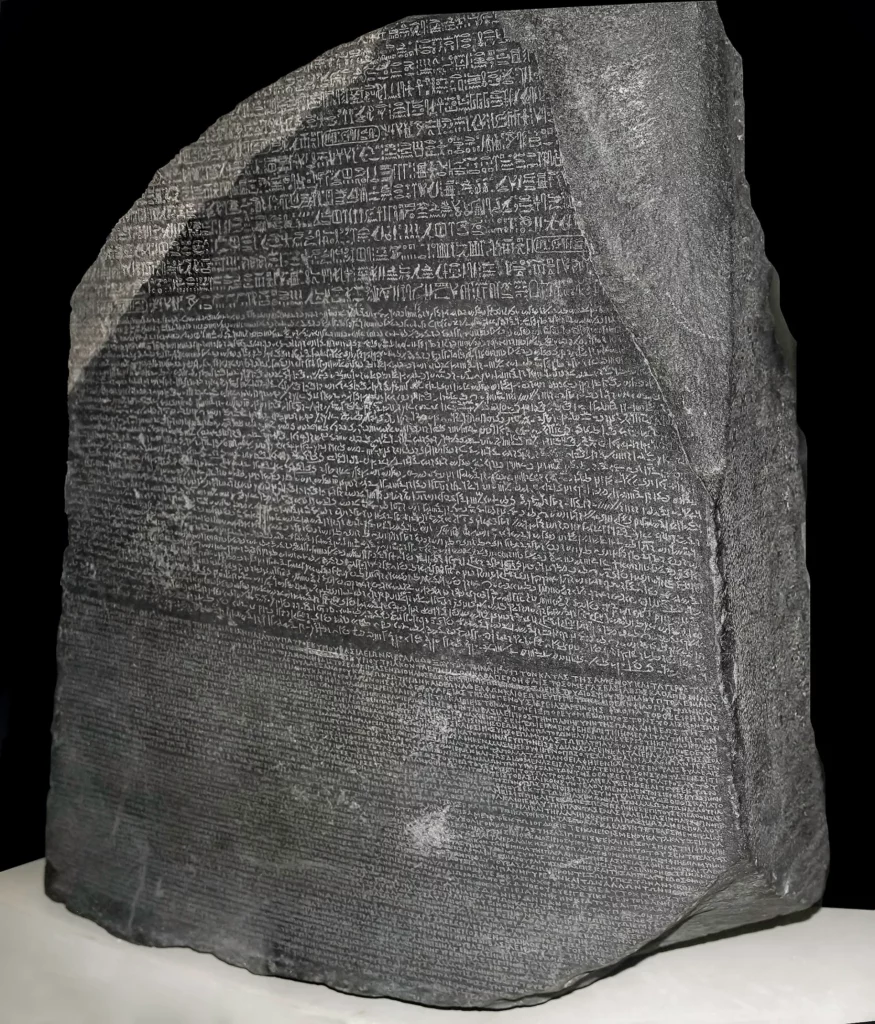

Rare evidence of a decades-long rebellion against Greek-Macedonian rule, mentioned in the Rosetta Stone, has been found in an ancient Egyptian city.

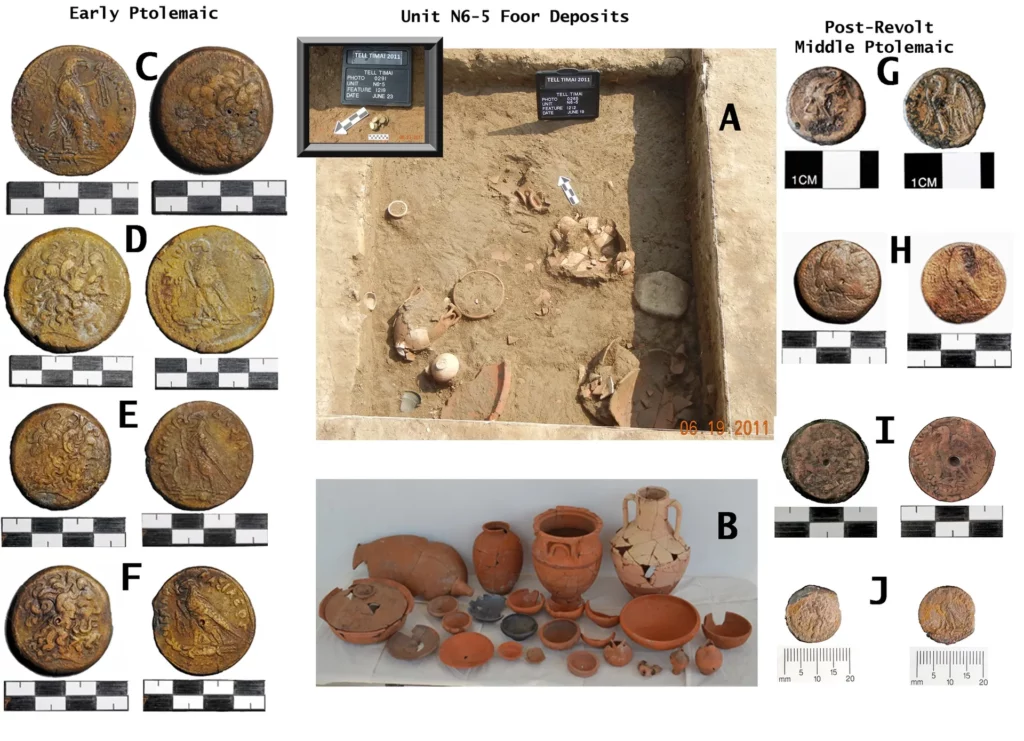

Excavations at Tell Timai, ancient Thmouis, 102km north of Cairo, revealed extensive destruction that occurred during the Great Revolt, which happened from 207 to 184 BC.

“Archaeological evidence from the [revolt] is quite rare,” says Jay Silverstein of Nottingham Trent University, UK, one of the lead authors of the paper published in the Journal of Field Archaeology.

“There are of course a number of decrees and inscriptions, like the Rosetta Stone, some historical accounts, and a few papyri with indirect references, but when it comes to finding the locations where the sword meets the bone, as far as I can tell, this is the first that has been recognized.”

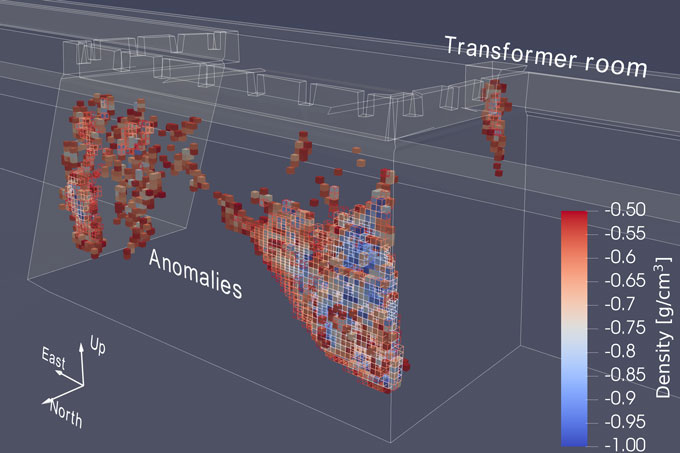

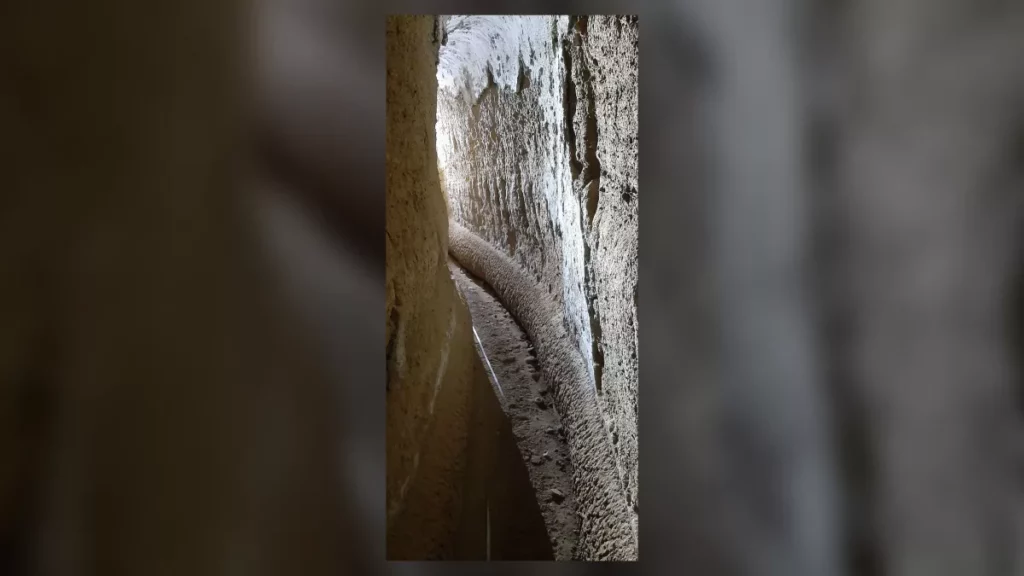

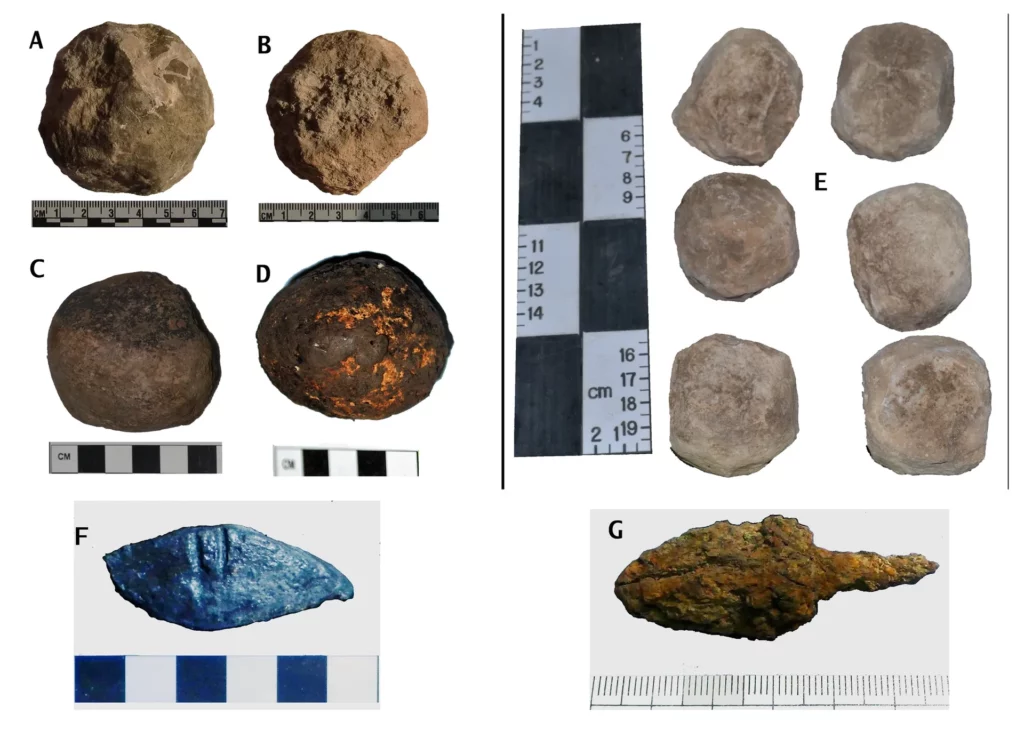

Over the course of several years, the team uncovered the remains of burned buildings, weapons, stones thrown by a siege engine, coins hidden beneath the floor of a house, a broken divine statue near a temple, and unburied bodies strewn among the ruins or dumped in mounds of rubble and refuse.

The skeleton of one young man was discovered with his legs sticking out of a large kiln, where he had perhaps hoped to hide from his attackers.

A man in his 50s, whose body displayed earlier healed wounds, appears to have died defending himself. He may have decomposed sitting upright.

By examining the pottery and coins, the team dated the destruction to the Great Revolt, when the Egyptians tried, but failed, to liberate themselves from Ptolemaic rule—the line of Greek-Macedonian kings that began after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt and ended with the famous Cleopatra VII.

“We have opened a new door into our understanding of Hellenistic colonialism, indigenous resistance, and the mechanisms of control including the brutality of the Macedonian dynasty’s rule of Egypt,” says Silverstein.

“Many other cities suffered a similar fate to that of Thmouis and I hope that this discovery will help broaden the scope of our archaeological understanding of these events.”

The discovery made Silverstein reconsider how decisive the events of the rebellion were in the development of the Western world.

“Hellenistic Egypt played a crucial role in the trajectory of history including its role as a crucible of Christianity and a bulwark of Roman imperial power. Had the Egyptians retaken their land from the Greek occupiers, I suspect the world would look significantly different today.”