Old bone links lost American parrot to ancient Indigenous bird trade

For centuries, Indigenous communities in the American Southwest imported colourful parrots from Mexico. But according to a study led by The University of Texas at Austin, some parrots may have been captured locally and not brought from afar.

The research challenges the assumption that all parrot remains found in American Southwest archaeological sites to have their origins in Mexico. It also presents an important reminder: The ecology of the past can be very different from what we see today.

“When we deal with natural history, we can constrain ourselves by relying on the present too much,” said the study’s author, John Moretti, a doctoral candidate at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences. “These bones can give us kind of a baseline view of the animal life of the ecosystems that surrounded us before huge fundamental changes that continue today began.”

The study was published in print in the September issue of The Wilson Journal of Ornithology.

Parrots are not an uncommon find in southwestern archaeological sites dating as far back as the 7th or 8th centuries. Their remains have been found in elaborate graves and buried in trash heaps. But no matter the condition, when archaeologists have discovered parrot bones, they usually assumed the animals were imports, said Moretti.

There’s a good reason for that. Scarlet macaws — the parrot most commonly found in the archaeological sites — live in rainforests and savannahs, which are not part of the local landscape. And researchers have discovered the remains of ancient parrot breeding facilities in Mexico that point to a thriving parrot trade.

But there is more to parrots than macaws. In 2018, Moretti found a lone ankle bone belonging to a species known as the thick-billed parrot. It was part of an unsorted bone collection recovered during an archaeological dig in the 1950s in New Mexico.

“There was a lot of deer and rabbit, and then this kind of anomalous parrot bone,” said Moretti, a student in the Jackson School’s Department of Geological Sciences. “Once I realized that nobody had already described this, I really thought there was a story there.”

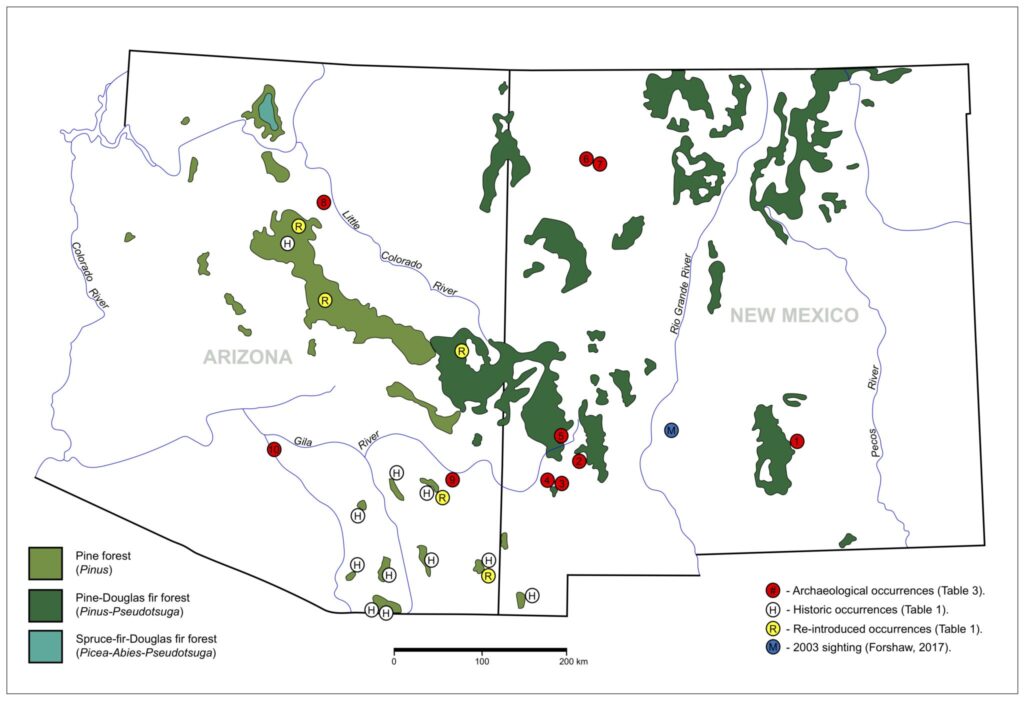

Thick-billed parrots are an endangered species and do not live in the United States today due to habitat loss and hunting. But that was not the case even a relatively short time ago. As recently as the 1930s, their range stretched from Arizona and New Mexico to northern Mexico, where they live today. The boisterous, lime-green birds are also very particular about their habitat. They dwell only in mountainous old-growth pine forests, where they nest in tree hollows and dine almost exclusively on pine cones.

With that in mind, Moretti decided to investigate the connection between pine forests in New Mexico and Arizona and the remains of thick-billed parrots found at archaeological sites. He found that of the 10 total archaeological sites with positively identified thick-billed parrot remains, all contained buildings made of pine timber, with one settlement requiring an estimated 50,000 trees. And for half the sites, suitable pine forests were within 7 miles of the settlement.

Moretti said that with people entering parrot habitat, it’s plausible to think they captured parrots when gathering timber and brought them home.

“This paper makes the hypothesis that these [parrots] were not trade items,” Moretti said. “They were animals living in this region that were caught and captured and brought home just like squirrels and other animals that lived in these mountains.”

Moretti relied on thick-billed parrot bones from the United States and Mexico permanently archived in collections at The University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute and the Smithsonian Institution to conclusively identify the lone bone that sparked the research.

Mark Robbins, an evolutionary biologist and the collection manager of the ornithological collections at The University of Kansas, said this study shows the value of natural history collections and the innumerable ways they assist with research.

“The scientists who originally collected those specimens, they had no idea they would be used in this fashion,” Robbins said. “You can revisit old questions or formulate new questions based on these specimens.”

The research was funded by the Museum of Texas Tech University, where Moretti earned a master’s degree.