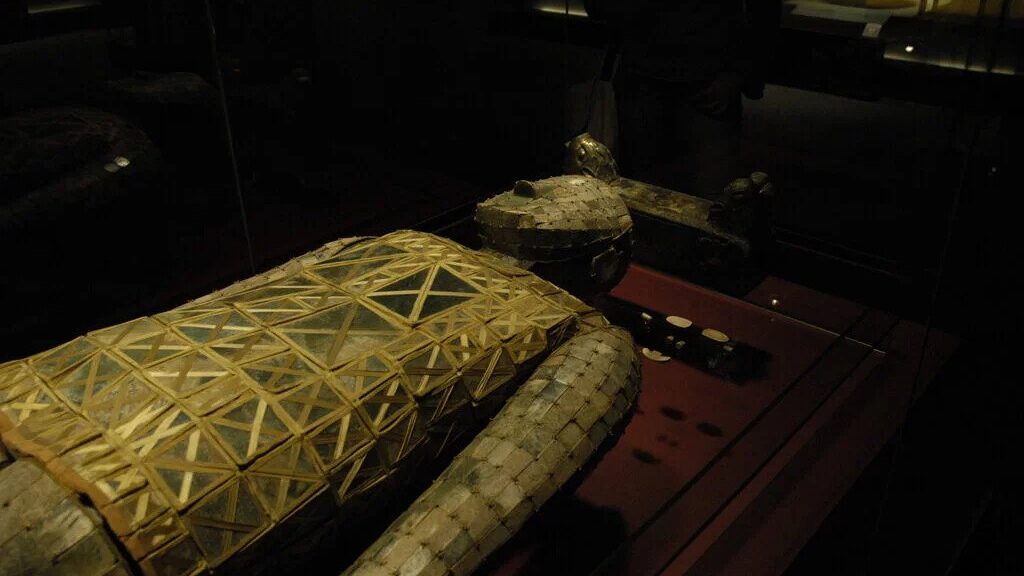

The Immortal Armour of China Jade burial suits

Threaded hand-crafted from thousands of precious stone slabs with silver and gold during the Han Dynasty about 2000 years ago, ancient China’s jade burial suits were built as armour for the afterlife to prevent mortal decay.

The Jude Burial Suits of China are maybe the most opulent type of burial in history. Ceremonial suits composed of jade and gold thread were the chosen way of afterlife immortality for Han Dynasty China’s royal members.

Small discs strung onto necklaces as emblems of political power and religious authority, or ceremonial instruments like axes, knives, and chisels, were fashioned from nephrite jade.

Jade became associated with Chinese conceptions of the soul, protective properties, and immortality in the ‘essence’ of stone over time due to its hardness, durability, and delicate transparent hues (yu Zhi, shi Zhi jing ye).

With the rise of the Han Dynasty (China’s second imperial dynasty) in 202 BC-AD, 9 AD and AD 25 AD–220 AD, the association with jade’s longevity is clear from the text by the Chinese historian Sima Qian (145 – 86 BC) about Emperor Wu of Han (157 BC–87 BC), who was described as having a jade cup inscribed with the words “Long Life to the Lord of Men,” and indulging with an elixir of jade powder mixed with sweet dew.

Jade articles were first documented in literature around 320 AD, although there is archaeological evidence that they existed earlier than half a century.

However, their existence was not verified until 1968, when the tomb of Han Dynasty ruler Liu Sheng and his wife Princess Dou Wan was found.

The undisturbed tomb, said to be one of the most important archaeological findings of the twentieth century, was discovered in Hebei Province behind an iron wall between two brick walls and a passageway packed with stone.

They were composed of hundreds of tiny jade plates stitched together with gold thread. There were also jade pieces designed to conceal the eyes and plugs to fit into the eyes, ears, and other orifices.

All in the sake of keeping the bad at bay. Each suite is divided into twelve sections: the face, head, front and rear portions, arms, gloves, leggings, and feet. Liu Sheng’s outfit was very opulent. It was composed of 2498 pieces of jade that were stitched together with 1.1kg of gold thread and took an estimated 10 years to complete. On occasion, the remains were also placed in elaborate jade-covered coffins, which were equally spectacular, having been constructed with hundreds of solid gold nails.

Sets of instructions and standards for how the outfits should be made were also discovered. These rules are detailed in “The Book of Later Han.”

However, a study of the suits reveals that they were not always designed to meet the stated standards. The quality of the 15 outfits revealed varies.

The type of thread used was determined by the deceased’s status, according to Hu Hànsh (The Book of the Later Han). An emperor’s jade suit was threaded with gold, lessor royals and high-ranking nobles wore silver threaded jade suits, sons and daughters of the lessor wore copper threaded jade suits, and lower-ranked aristocrats wore silk threaded jade suits.

Emperor Wen of Wei ordered that the production of jade suits be stopped, as they encouraged tomb looters who would burn the suits to retrieve the gold thread in AD 223.

Jade failed to prevent soft tissue deterioration. Nonetheless, because jade is permeable, DNA from the royal pair may be entrenched in the stones for 2,000 years after their deaths, granting them a kind of immortality.