Fossil of a beetle inside a lizard inside a snake – an ancient food chain

Paleontologists have uncovered a fossil that has preserved an insect inside a lizard inside a snake – a prehistoric battle of the food chain that ended in a volcanic lake some 48 million years ago.

Pulled from an abandoned quarry in southwest Germany called the Messel Pit, the fossil is only the second of its kind ever found, with the remains of three animals sitting snug in one another.

Earlier excavations have revealed the fossilized stomach contents of a prehistoric horse, whose last meal was grapes and leaves, and pollen grains were identified inside a fossilized bird. Remains of insects have also been detected in a sample of fish excrement.

We have been lucky to glimpse such a primordial food chain of the snake, that ate a lizard, that had previously treated itself to a beetle, and ended up in a volcanic lake of the time. It is uncertain how the snake died.

Perhaps the snake’s body fell dead close to the shores of the lake before the waters claimed it. It had died there not more than 48 hours after its “last supper,” scientists say.

“It’s probably the kind of fossil that I will go the rest of my professional life without ever encountering again, such is the rarity of these things.” Such are the words of Dr. Krister Smith, a paleontologist at the Senkenberg Institute in Germany who took charge of the fossil analysis.

According to Dr. Smith, the almost entirely preserved snake was recovered from a plate found in the pit back in 2009, and the discovery soon turned out to be groundbreaking. Smith remarks, “we had never found a tripartite food chain–this is a first for Messel.”

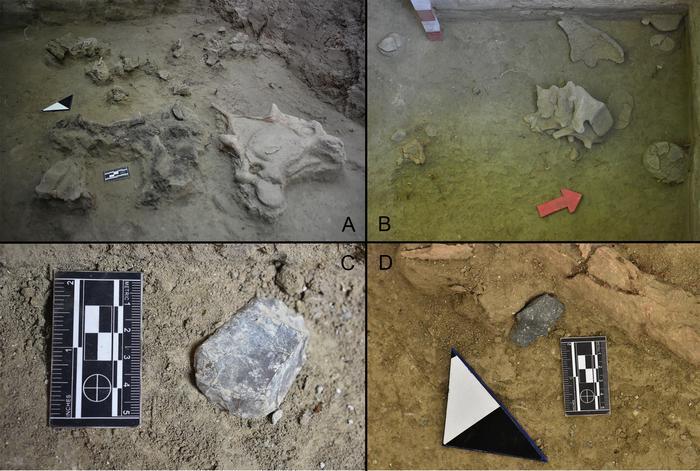

Dr. Smith and Argentine paleontologist Dr. Agustín Scanferla used high-resolution computer imaging to identify the taxonomy of the snake and the lizard, however, they were unable to name the beetle, the least preserved of the three.

The snake, measuring some 3.4 feet in length, was identified as Palaeophython fischeri, a species which belongs to a group of tree-dwelling snakes that was able to grow to more than 6.5 feet in length and is related to today’s boas.

The preserved sample from Germany was only a juvenile, an assurance being not only the shorter length but also its food choice, the lizard. Adult boas are known to opt for bigger animals.

The lizard would have measured nearly eight inches and a clear hint for paleontologists that it was inside the snake’s body was that the snake’s ribs overlapped it.

It is an example of the now extinct species Geiseltaliellus maarius, a type of iguanian lizard that inhabited the region of what is now Germany, France, and Belgium. Messel has been the site that has provided some of the best-preserved samples of this lizard species.

What’s also interesting is that, even though lizards are known for shedding their tails when under threat, this one has kept it despite falling prey to the snake.

“Since the stomach contents are digested relatively fast and the lizard shows an excellent level of preservation, we assume that the snake died no more than one to two days after consuming its prey and then sank to the bottom of the Messel Lake, where it was preserved,” explained Dr. Smith.

This is a rare type of fossil, but it’s not the first instance in which a fossil has simultaneously exposed three levels of an ancient food chain. According to National Geographic, in 2008, a fossil dated at more than 250 millions of years old depicted a shark that had devoured an amphibian that had previously consumed a spiny-finned fish.

Both these findings are precious as they reveal significant details on how food chains functioned. In the case of the snake fossil, it is interesting that the lizard had eaten a beetle.

Before that, scientists didn’t know that the Messel lizard liked to dine on insects, as in previous digs they had been able to identify only remains of plants in fossilized lizard bellies. In the case of the shark, it was revealed that amphibians consumed fish before becoming a menu item to the fish itself.