Traces of 3,600-Year-Old Settlement Found in Qatar’s Desert

Scholars looking for underground water sources on the Eastern Arabian Peninsula for a project funded by the United States Agency for Aid and International Development have accidentally uncovered the outlines of a settlement that appears to be over 3600 years old. Asymmetrical 2 x 3 kilometre, landscaped area—or trace outlines of a settlement (and one of the largest potential settlements uncovered in the area) was identified using advanced radar satellite images in an area of Qatar where there was previously thought to be little evidence of sedentary, ancient civilizations. Their new study, published in the ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, counters the narrative that this peninsula was entirely nomadic and evidence mapped from space indicates that the population appears to have had a sophisticated understanding of how to use groundwater. The research also points to the critical need to study water and safeguard against climate fluctuations in arid areas.

“Makhfia,” the name attributed to the settlement by researchers at the University of Southern California Viterbi School of Engineering and NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (and which refers to an invisible location in the local Arabic language), was discovered using L-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar images from the Japanese Satellite ALOS 1 and specially acquired, high-resolution radar images by its successor, ALOS 2. While the settlement was not visible from space using normal satellite imaging tools nor through surface observation on the earth—the large, underground rectangular plot, it was determined, had to be manmade due to its shape, texture and soil composition which were in sharp contrast to surrounding geological features.

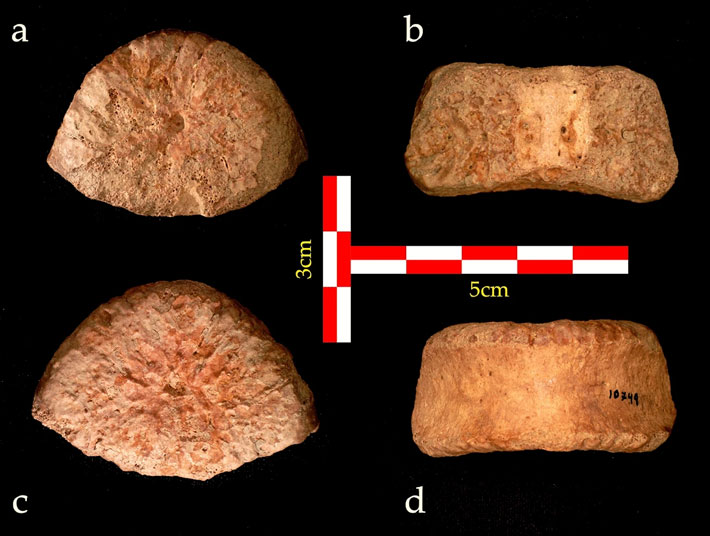

Independent carbon dating of retrieved charcoal samples suggests that the site is at least 3650 years old, dating back potentially to the same era of the Dilmun civilization.

Lead author, Essam Heggy, of the USC Arid Climate and Water Research Center, describes the site as akin to a “natural fortress surrounded by very rough terrain,” almost making the area inaccessible.

This discovery has significant historic and scientific implications. Historically, this may be the first piece of evidence of a sedentary community in the area—and perhaps evidence of advanced engineering for the time period. While we cannot see the remains of a monument or walls of a settlement, the proof is in the soil. The properties of the soil at the site have a different surface texture and composition than the terrain surrounding it—a disparity typically associated with planting and landscaping.

A settlement of this size in this particular area, which is far from the coastline where most ancient civilizations were located, is unusual, says Heggy.

“With this area now averaging about 110 degrees Fahrenheit in summer months, this is like finding evidence of very green ranch in the middle of Death Valley, California dating back thousands of years ago.”

Further, the site yields new insights on the poorly understood climatic fluctuations that occurred in the region, and how these changes may have impacted human settlement and mobility.

Most critically, the scholars believe that this settlement must have been in place for an extended period due to its development of agriculture and reliance on groundwater, a fact which speaks to the civilization’s advanced engineering prowess given Qatar’s complex aquifers and harsh terrain.

The researchers believe that a population with sufficient knowledge to leverage such unpredictable groundwater resources— inaccessible by digging through hard limestone and dolomite—would have certainly been ahead of its time in mitigating droughts within harsh, inland environments. There is strong evidence that this settlement’s inhabitants relied on deep groundwater sapping, a method by which one accesses water from deeper aquifers through fractures in the ground, in order to use this water for crop irrigation and to support daily life.

This presence of this settlement is now enabling researchers to piece together the most recent paleoclimatic changes that took place on the Eastern Arabian Peninsula.

The bleak side of this, says Heggy, is that we do not fully know who this culture was and why they disappeared. However, based on the presence of charcoal found on the site, Heggy and his colleagues suggest that fire could be one of several plausible explanations for its demise.

This evidence calls for increased study of this area by archaeologists, says Heggy.

The work also has some implications for how we study and address climate fluctuations today.

“Deserts cover about 10 per cent of our planet. We might think today that they were always inhabitable, but this discovery (along with others in the area) shows that this might not have been always the case,” says Heggy who is a research scientist at the Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical Engineering at USC.

His concern is that the increase in climate fluctuations in arid areas can worsen food insecurity, migration, and degradation of water resources.

Why should people care about the ruins of this ancient settlement? To Heggy, this culture’s ability to mitigate climatic fluctuations could be our story.

“This story is very important today. In arid areas, we have widespread disbelief in climate research. Many think climate change is something in the future or far away in the ‘geologic’ past. This site shows that it has always been here and that our recent ancestors have made its mitigation a key to their survival,” he says.

Heggy remains hopeful. He says the forthcoming NASA Earth Observation missions focused on desert research will bring new subsurface mapping capabilities and will provide unique insights on deserts’ paleoclimatic evolution as well as a human presence in desert areas during climate fluctuations.