Armored Dinosaur’s Last Meal Found Preserved in Its Fossilized Belly

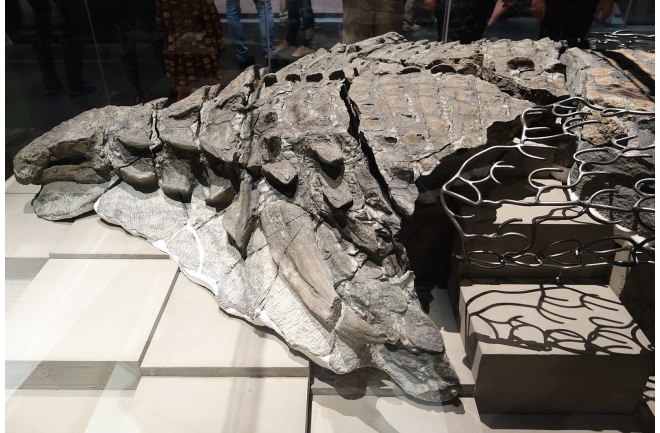

More than 110 million years ago, a lumbering 1,300-kilogram, armour-plated dinosaur ate its last meal, died, and was washed out to sea in what is now northern Alberta. This ancient beast then sank onto its thorny back, churning up mud in the seabed that entombed it — until its fossilized body was discovered in a mine near Fort McMurray in 2011.

Since then, researchers at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alta., Brandon University, and the University of Saskatchewan (USask) have been working to unlock the extremely well-preserved nodosaur’s many secrets — including what this large armoured dinosaur (a type of ankylosaur) actually ate for its last meal.

“The finding of the actual preserved stomach contents from a dinosaur is extraordinarily rare, and this stomach recovered from the mummified nodosaur by the museum team is by far the best-preserved dinosaur stomach ever found to date,” said USask geologist Jim Basinger, a member of the team that analyzed the dinosaur’s stomach contents, a distinct mass about the size of a soccer ball.

“When people see this stunning fossil and are told that we know what its last meal was because its stomach was so well preserved inside the skeleton, it will almost bring the beast back to life for them, providing a glimpse of how the animal actually carried out its daily activities, where it lived, and what its preferred food was.”

There has been lots of speculation about what dinosaurs ate, but very little is known. In a just-published article in Royal Society Open Science, the team led by Royal Tyrrell Museum palaeontologist Caleb Brown and Brandon University biologist David Greenwood provides detailed and definitive evidence of the diet of large, plant-eating dinosaurs — something that has not been known conclusively for any herbivorous dinosaur until now.

“This new study changes what we know about the diet of large herbivorous dinosaurs,” said Brown. “Our findings are also remarkable for what they can tell us about the animal’s interaction with its environment, details we don’t usually get just from the dinosaur skeleton.”

Previous studies had shown evidence of seeds and twigs in the gut but these studies offered no information as to the kinds of plants that had been eaten. While tooth and jaw shape, plant availability and digestibility have fuelled considerable speculation, the specific plant’s herbivorous dinosaurs consumed has been largely a mystery.

So what was the last meal of Borealopelta markmitchelli (which means “northern shield” and recognizes Mark Mitchell, the museum technician who spent more than five years carefully exposing the skin and bones of the dinosaur from the fossilized marine rock)?

“The last meal of our dinosaur was mostly fern leaves — 88 per cent chewed leaf material and seven per cent stems and twigs,” said Greenwood, who is also a USask adjunct professor.

“When we examined thin sections of the stomach contents under a microscope, we were shocked to see beautifully preserved and concentrated plant material. In marine rocks, we almost never see such superb preservation of leaves, including the microscopic, spore-producing sporangia of ferns.”

Team members Basinger, Greenwood and Brandon University graduate student Jessica Kalyniuk compared the stomach contents with food plants known to be available from the study of fossil leaves from the same period in the region. They found that the dinosaur was a picky eater, choosing to eat particular ferns (leptosporangiate, the largest group of ferns today) over others, and not eating many cycad and conifer leaves common to the Early Cretaceous landscape.

Specifically, the team identified 48 palynomorphs (microfossils like pollen and spores) including moss or liverwort, 26 clubmosses and ferns, 13 gymnosperms (mostly conifers), and two angiosperms (flowering plants).

“Also, there is considerable charcoal in the stomach from burnt plant fragments, indicating that the animal was browsing in a recently burned area and was taking advantage of a recent fire and the flush of ferns that frequently emerges on a burned landscape,” said Greenwood.

“This adaptation to a fire ecology is new information. Like large herbivores alive today such as moose and deer, and elephants in Africa, these nodosaurs by their feeding would have shaped the vegetation on the landscape, possibly maintaining more open areas by their grazing.”

The team also found gastroliths, or gizzard stones, generally swallowed by animals such as herbivorous dinosaurs and today’s birds such as geese to aid digestion.

“We also know that based on how well-preserved both the plant fragments and animal itself are, the animal’s death and burial must have followed shortly after the last meal,” said Brown. “Plants give us a much better idea of the season than animals, and they indicate that the last meal and the animal’s death and burial all happened in the late spring to mid-summer.”

“Taken together, these findings enable us to make inferences about the ecology of the animal, including how selective it was in choosing which plants to eat and how it may have exploited forest fire regrowth. It will also assist in the understanding dinosaur digestion and physiology.”

Borealopelta markmitchelli, discovered during mining operations at the Suncor Millennium open-pit mine north of Fort McMurray, has been on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum since 2017. The main chunk of the stomach mass is on display with the skeleton. Other members of the team include museum scientists Donald Henderson and Dennis Braman, Brandon University research associate and USask alumna Cathy Greenwood.

Research continues on Borealopelta markmitchelli — the best fossil of a nodosaur ever found — to learn more about its environment and behaviour while it was alive. Student Kalyniuk is currently expanding her work on fossil plants of this age to better understand the composition of the forests in which they lived. Many of the fossils she will examine are in Basinger’ collections at USask.

The research was funded by Canada Foundation for Innovation, Research Manitoba, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, National Geographic Society, Royal Tyrrell Museum Cooperating Society, and Suncor Canada, as well as in-kind support from Olympus Canada.