Over 300 mummified crocodiles were found at the temple of Kom Ombo in Egypt

Kom Ombo is one of the more unusual temples in Egypt. Due to the conflict between Sobek and Horus, the ancient Egyptians felt it necessary to separate their temple spaces within one temple. The Kom Ombo temple has two entrances, two courts, two colonnades, two Hypostyle halls and two sanctuaries, one side for each god.

Location

Built to overlook the Nile, the temple is located in the city of Kom Ombo, about 30 miles north of Aswan. Its dual design is dedicated to Sobek and Horus and is perfectly symmetrical along its main axis.

Kom Ombo History

The Kom Ombo Temple was built between 332 BC and 395 AD, during the Ptolemaic period, by Ptolemy VI Philometer.

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos continued the work and built the exterior and interior Hypostyle halls. The temple was built with local limestone by men who rode on elephants, considered to be a Ptolemaic innovation.

Little remains of the original structure. Unfortunately, a good portion of the temple has been destroyed over the millennia by earthquakes, erosion by the Nile River and builders who stole stone for unrelated projects. In 1893, a French archaeologist by the name of Jacques de Morgan cleared the Southern portion (the half dedicated to Sobek) of debris and restored it.

During the Roman period, additions to the temple were made in the form of decorations in the main court. At this time, an outer corridor was also added.

Augustus built an outer enclosure wall and a portion of the court, but those structures have since been lost. The Coptic Church took over the temple and converted it into its own place of worship. It was at this time that many of the ancient reliefs were defaced and removed.

Kom Ombo Temple Dedications

Kom Ombo was dedicated mainly to Sobek and Horus; however, some of their family members were part of the temple’s dedication as well.

The Southern portion of the temple was not just dedicated to Sobek, the god of fertility, but also to Hathor, the goddess of love and joy, and Khonsu, the god of the moon.

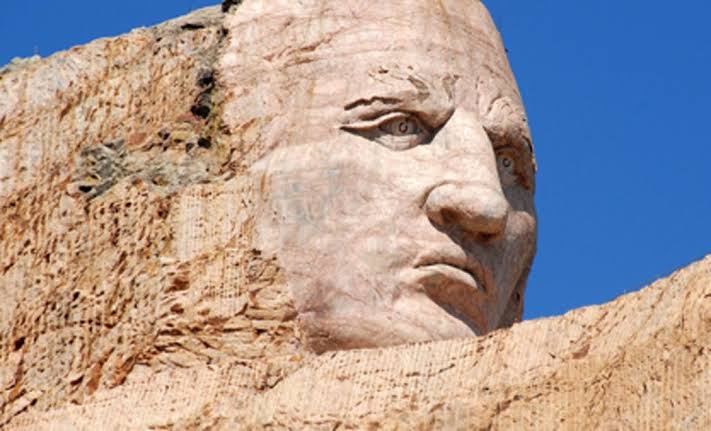

In this portion of the temple, there are many crocodile representations to pay homage to Sobek. This part of the temple is also called “House of the Crocodile.”

The Northern portion of the temple was dedicated mainly to Horus, god of the sun, and also Tasenetnofret, meaning “the good sister,” and a manifestation of Hathor, and Panebtaway, meaning “the Lord of two lands” which represented Egyptian kingship. In this part of the temple, there are many representations of falcons to pay homage to the falcon-headed god, Horus. This part of the temple is also called “Castle of the Falcon.”

Kom Ombo Temple Layout

Just after crossing the gate inside the temple, there is a small room dedicated to Hathor. Today, it is used to display the many mummified crocodiles that were found in the temple’s vicinity.

A well in front of the main entrance was once used as a Nilometer. The first pylon, which has since been destroyed, now consists only of foundation stones and a portion of a wall.

Entering into the main court, there are 16 painted columns, eight on each side of the court. A granite altar sits in the centre of the main court, likely where the sacred boat was placed.

On the rear wall of the main court are five lotus-shaped columns along with a screen wall. Two entrances, one for each deity, open up here. Through both entrances lies the first Hypostyle hall.

There are ten lotus-shaped columns here with the middle two separating the two halves of the hall.

Separate entrances guide visitors into the second Hypostyle hall known as “The Hall of Offering”. Beyond this Hall of Offering are three antechambers, now all nearly destroyed.

Curiously, the twin sanctuaries which are found beyond the antechambers are separated by a hidden chamber.

A dual passageway runs the perimeter of the entire temple and there are seven additional rooms along the interior passage. A staircase leads to the roof.