3,000-Year-Old Weapons Cache Unearthed In Arabia

In the Arabian Peninsula, an impressive hoard of bronze weapons dating back nearly 3,000 years has been discovered. Bows, arrows, daggers, and axes were discovered strewn around the ruins of what is thought to be an ancient religious building.

Are these all replicas? They are intriguing because they are crafted from metal and considered sacred in some people’s cultures, as a possible offering to a god of war.

They were found inside the ruins of an Iron Age building first discovered in 2009 near Adam, in the Sultanate of Oman.

Experts believe the weapons, which date from 900 to 600 BC, were once displayed on shelves, furniture, or hung on walls before they fell off and were discovered alongside ritualistic objects. Two collections of items are of particular interest to archaeologists – small quivers entirely made of bronze, each containing six arrows and other metal weapons.

They measure 14 inches (35cm) tall, making them small-scale replicas of the real objects, which would have been made of leather and are not usually found in archaeological excavations as they degrade over time.

The fact the quivers are made of metal supports the idea they were ornamental objects, rather than of practical use. Quivers of this kind have never been found in the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East, and are extremely rare elsewhere.

Experts are also intrigued by other metal weapons, which were also mostly non-utilitarian given their slightly reduced size, material, or unfinished state.

They include five battle-axes, five daggers with crescent-shaped pommels characteristic of the Iron Age, around 50 arrowheads, and five complete bows.

The bows are made up of a flat, curved stave bent at both ends which are connected by a string made of bronze. The size of the bows – 28 inches (70cm) on average – and above all the material used, shows that they were imitations of the real things made of perishable materials such as wood and tendons.

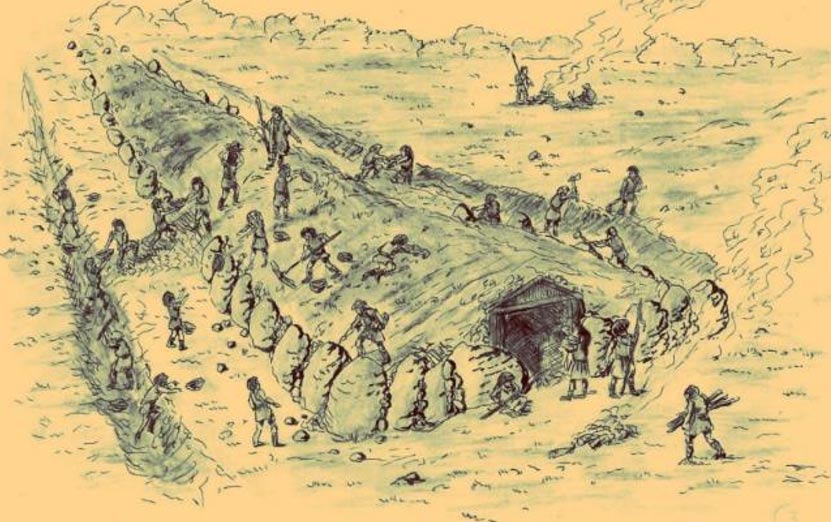

French archaeologists first discovered the site near Adam, which was completely unexplored from an archaeological point of view until the French mission headed by Dr. Guillaume Gernez, of Pantheon-Sorbonne University, began in 2011.

The site is known as Mudhmar East and consists of two main buildings located near one of the largest valleys in Oman which lay at the crossroads of several trade routes.

With a length of 49 feet (15 meters) the larger of the two buildings is located on the slope of Jabal Mudhmar and is made of cut sandstone blocks and earth bricks.

It is in this building, in a small, apparently doorless room, Dr. Gernez uncovered the bronze weapons.

‘This exceptional discovery provides new information about weaponry during the Iron Age in the eastern Arabian Peninsula and about social practices at the time,’ he said.

‘The non-utilitarian nature of most of the weapons may indicate that they were designed to be offered to a deity of war, and/or as a key element in social practices not yet understood.

‘The first hypothesis is reinforced by the presence in the site’s second building of several fragments of ceramic incense burners and small bronze snakes, objects often associated with ritual practices at that time.’

He said the cache of weapons was made at a time when metallurgical production was on the rise in the eastern Arabian Peninsula during the Iron Age.

‘This economic and technical development went hand-in-hand with an increasingly complex society, as shown by the proliferation of fortified sites and monumental architecture,’ he explained.

‘However, understanding the political system and social structure of this pre-literate society remains a difficult task.

‘Continued archaeological exploration of the site and its immediate surroundings, as well as of the central region of Oman, will be key to reconstructing the dawn of history in the Arabian Peninsula.’