Jerusalem’s Western Wall yields four 1,000-year-old gold coins

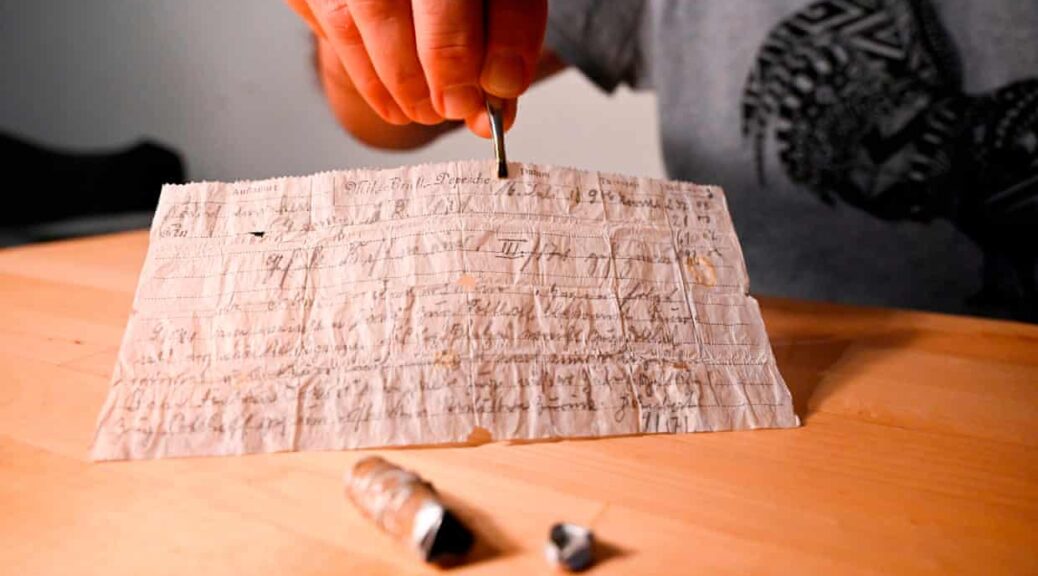

Four gold coins were recently found in a pottery jar uncovered during an excavation in West Wall Plaza in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The valuable 1000-year-old coins show the political and historic power change between the two Muslim dynasties that controlled the city at the time.

A little juglet or bottle was discovered about two months ago by inspector Yevgenia Kapil of the Israel Antiquity Authority about two months ago, during preliminary digging as part of a plan by the Jewish Quarter Development Corporation to build an elevator facilitating access to the plaza from the Jewish Quarter.

Last month, archaeologist David Gellman, director of the excavation, emptied out the dirt inside the juglet and discovered four gold coins in excellent condition.

Robert Kool, the antiquities authority’s coin expert, examined them and determined that they dated from the late 940s through 970s C.E., the early Islamist era.

Two of the coins are gold dinars that were minted in Ramle under the rule of the Caliph Al-Muti’ (946-974) and his regional governor, Abu ‛Ali al-Qasim ibn al-Ihshid Unujur (946-961 C.E.).

The other two coins were minted in Cairo by the Fatimid rulers al-Mu‘izz (953-975 C.E.) and his successor, al-‘Aziz (975-996 C.E.).

“The profile of the coins found in the juglet is a near-perfect reflection of the historical events.

This was a time of radical political change, when control over Eretz Israel passed from the Sunni Abbasid caliphate, whose capital was Baghdad, Iraq, into the hands of its Shiite rivals – the Fatimid dynasty of North Africa,” Dr Kool explains.

“Four dinars was a considerable sum of money for most of the population, who lived under difficult conditions at the time.

It was equal to the monthly salary of a minor official, or four months’ salary for a common labourer,” he says, adding that for members of the elite in those days, however, it was a relatively small sum.

“The small handful of wealthy officials and merchants in the city earned huge salaries and amassed vast wealth.

A senior treasury official could earn 7,000 gold dinars a month, and also receive additional incomes from his rural estates amounting to hundreds of thousands of gold dinars a year.”