World’s Oldest Shoes: Some Look Surprisingly Modern

More than 700 years ago today, on May 20, 1310, shoes were made for the first time for both right and left feet. Before that, unfortunately, they weren’t.

Archaeologists have discovered several very old shoes in many parts of the world. Some of the shoes are thousands of years old and in remarkably good condition. Here we present some of the oldest shoes discovered worldwide, and as you can see, some of them look surprisingly modern.

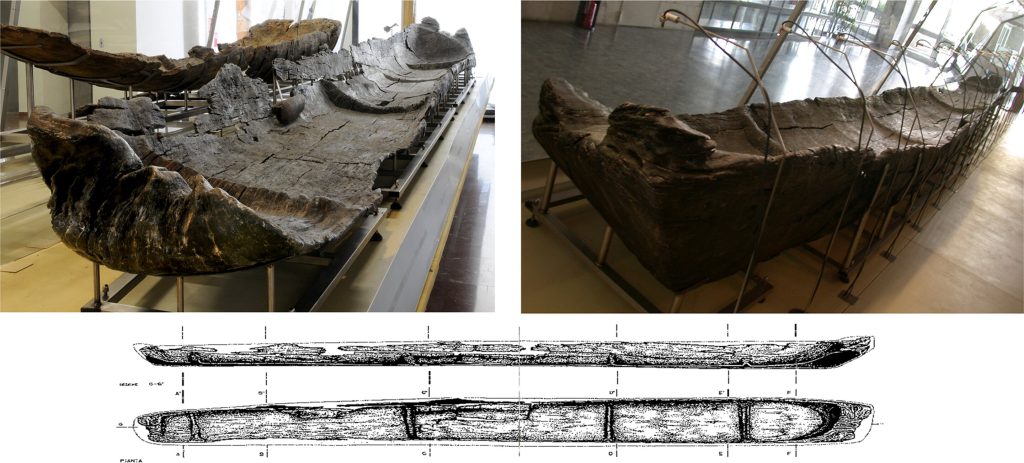

The Areni-1 shoe: World’s Oldest Shoe Was Found In A Cave In Armenia

The world’s oldest shoe was discovered in Armenian cave and is around 5,500 years old. It’s older than the ancient Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge. Known as the Areni-1 shoe, the moccasin-like shoe is compressed in the heel and toe area, likely due to miles upon miles of walking. However, the shoe is by no means worn out, and it’s still in very good condition. Researchers and designers have emphasized it is astonishing how much this shoe resembles a modern shoe.

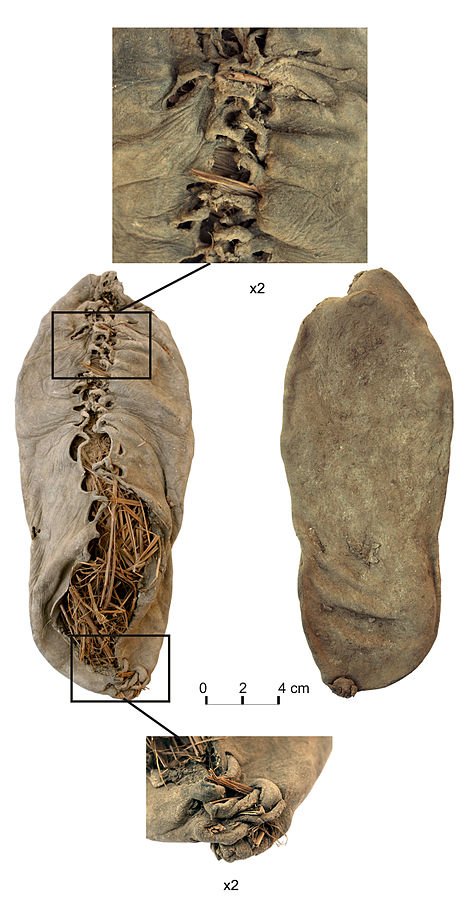

Iceman Ötzi’s Shoes

The Iceman Ötzi’s shoes were long regarded as the oldest known shoes until the discovery of the 5,500-years old Armenian shoes. Ötzi’s shoes are sophisticated and consist of an inner and outer part.

The inner shoe is composed of grass netting. Its purpose was to hold hay in place, which served as insulation material. The outer part is made of deerskin. Both parts – the grass netting and the leather upper – are fastened to an oval-shaped sole made of bearskin by means of leather straps. Unlike the sole, the uppers were worn with fur on the outside. The shaft around the ankle was bound with grass fibers.

World’s Oldest Sandals Were Discovered In Fort Rock Cave, Oregon

The word sandal derives from the Greek word sandal. The ancient Greeks distinguished between baxeae (sing. baxea), a sandal made of willow leaves, twigs, or fibers worn by comic actors and philosophers, and the cothurnus, a boot sandal that rose above the middle of the leg, worn principally by tragic actors, horsemen, hunters, and by men of rank and authority. The sole of the latter was sometimes made much thicker than usual by the insertion of slices of cork, so as to add to the stature of the wearer.

Sandals were popular among ancient Egyptians. They wore sandals made of palm leaves and papyrus.

The world’s oldest sandals were discovered in 1938 by anthropologist Luther Cressman in Fort Rock Cave, Oregon, United States. Cressman came across dozens of sandals and fragments of sandals inside the cave. They were found beneath a layer of volcanic ash, which was later identified as coming from the eruption of Mount Mazama.

Cressman believed that the sandals were ancient, but because radiocarbon dating would not be developed for another decade, his conviction would not be confirmed until 1951, when fibers from the sandals themselves were dated to more than 9,000 years old. Fort Rock sandals are made of shredded sagebrush bark. They are twined, with pairs of fiber wefts twisted around passive warps, in contrast to simple over-and-under interlacing or plaiting, known as wickerwork.

3,000-Year-Old Shoe Found On A Beach In Kent, UK

The shoe as it was found on a foreshore in North Kent. Credit: Steve Tomlinson Britain’s oldest shoe has been found on a beach in Kent. The shoe, made of leather, is 3,000 years old and was discovered by archaeologist Steve Tomlinson.

When Tomlinson found the shoe, he did not think it was special, but he sent it for carbon dating at an East Kilbride, Scotland unit. Five weeks later, he received a reply stating the shoe was from the late Bronze Age.

1,700-Year-Old Roman Shoes Found In France

Archaeologists excavating in the small village of Thérouanne, located on the river Lys in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France have made some fascinating discoveries. Scientists unearthed 1,700-year-old Roman shoes that are still in good condition and an exceptional glass workshop.

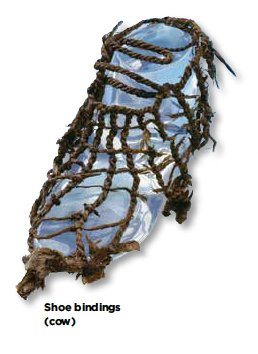

Startling Roman-Looking Sandal Discovered Buried Deep Beneath The Snow In Norwegian Mountains

Team Secrets of the Ice has been searching for clues about the past in the Norwegian mountains for 15 years, and during this time the scientists have made many unusual discoveries.

Among the most significant finds are the hundreds of pre-historic cairns, which are stone structures that signaled to the travelers where the route went, a lost Viking settlement, an iron horseshoe as well as ancient textiles.

One curious find is the startling Roman-looking sandal that scientists found buried deep beneath the snow in an ancient, dangerous Norwegian mountain pass.

Oldest Shoe Discovered In Canada

The oldest shoe discovered in Canada is a 1,400-year-old made of deerskin found in a glacier region.

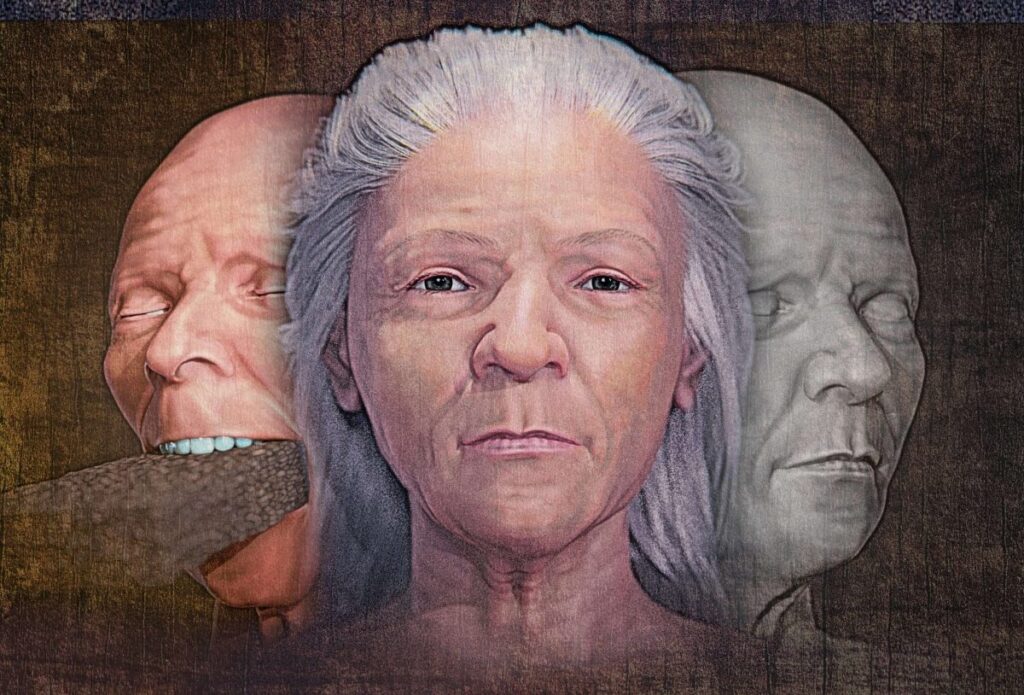

Who Did These Ancient Foreign Shoes Belong To?

In 2004, an Italian archaeological team discovered ancient shoes that were deliberately hidden in an Egyptian temple.

The two pairs of children’s shoes were among the seven found concealed in a jar placed into a cavity between two mudbrick walls in a temple in Luxor, the site of the ancient city of Thebes.

Oddly, the shoes were tied together using palm fiber string and placed within a single adult shoe. A third pair that an adult had worn was found alongside them. The shoes were obviously of foreign origin, as they were concealed at a time when most Egyptians would normally have worn sandals. The shoes were expensive and in pristine condition, at least at the time of discovery. Unfortunately, after they were unearthed, the shoes became brittle and ‘extremely fragile,

Who the owner of the shoes was has never been determined. “The shoes were eye-striking at the time. If you wore such shoes, “everybody would look at you,” wrote Dr. Veldmeijer, assistant director of the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo and an expert in ancient Egyptian footwear in the Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt.