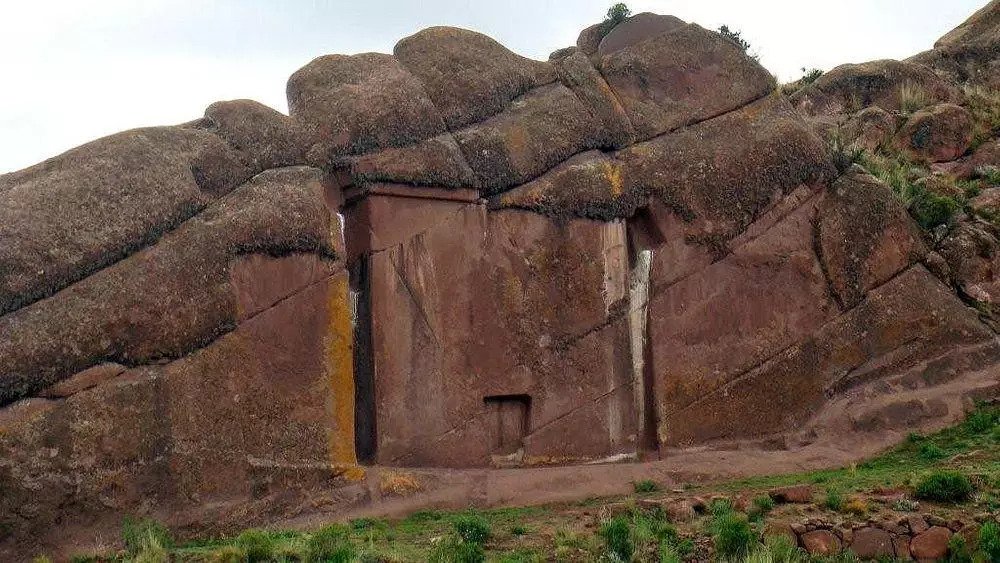

Mysterious Giant Stone Sculpture of Aramu muru north of Chucuito Peru

Many people here only see an unfinished work by ancient masons. Nevertheless, other local legends tell something else — Aramu Muru is called a gateway to a realm of spirit.

It is unclear when and who made Aramu Muru – but presumably before the Incas. No archaeological research has been done here.

This massive stone gateway is located in the uncommon location of Hayu Marca Stone Forest (‘the city of the Goods’), on the banks of Lake Titicaca. Giant crests of red granite rise from the dry soil of Altiplano here. Erosion processes have formed natural bridges, weird grottoes, and natural sculptures. Often it is hard to tell whether some weird shapes have been formed by nature or by humans.

Aramu Muru is cut in the side of one such granite crest. This portal is 7 m high and 7 m wide, with a “T” shaped alcove in the bottom middle. The surface of the portal is polished. Alcove is some 2 m high – one man can fit into it. In the center of the alcove is a smaller depression.

On the other side of the cliff in earlier times was located a tunnel, which is blocked now with stones to prevent mishaps with children. Some believe that this tunnel was going to Tiahuanaco.

Similar Monuments

It seems – there are no similar landmarks in the Americas. Often there is noted that Aramu Muru is similar to the Sun Gate in the nearby Tiwanaku – but Wondermondo does not see many similarities.

Aramu Muru has some principal similarities to the unfinished rock-cut architecture in India. Son Bhandar Caves (Bihar) have an unfinished portal inside the rock-cut cave. Local legends there tell about incredible riches inside.

Local tourist guide Jose Luis Delgado Mamani had unusual dreams in the 1990s. He saw a weird, red mountain with a gate cut in it. The door of this portal was open and blue, shimmering light was shining out of it.

Mamani was surprised to find mountains similar to the ones in his dream. He asked the local old men whether there are some gates cut in these cliffs – and, yes, they confirmed – there is a gate. Some tried to dissuade Mamani from going there – “this is the true gate to the hell”.

When Mamani reached the gate, he almost passed out from excitement – this was the site that he saw in his dreams. This story made into local newspapers and somewhat later – into the international press. The old, exotic story about Aramu Muru became popular again.

Legend about Aramu Maru

According to a local legend (maybe – a bit embellished by some contemporary mystics), this gate leads to the spirit world or even – to the world of gods.

Portal for the Immortals

The portal was made in the distant past. In those times the great heroes could pass the portal and join the pantheon of gods. Sometimes though these gods return to the land through these gates “to inspect all the lands in the kingdom”.

Golden Discs

Legends tell that the gate was open for a while in the 16th century. Back then Spanish Conquistadors were looting the immense treasures in Cusco city and slaughtering local people.

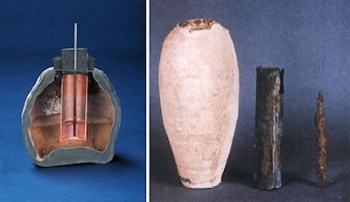

In the most important Inca temple – in Coricancha temple (now the Church of Santo Domingo stands there) – were located especially valuable relics – the golden discs.

According to the legend, these discs were given by gods to Inca. Discs had powerful healing abilities. Two of these discs were seized by Spaniards, but the third one – the largest – disappeared without a trace.

Escape from Cusco to… The Otherworld

A priest of Coricancha temple – Aramu Muru – managed to escape from the deadly havoc in Cusco. He took the large golden disc with him.

Aramu Muru reached the Hayu Marca hills and hid there for a while. He stumbled on Inca priests – guardians of the portal and when the guardians saw the golden disc, there was arranged a special ritual at the gate.

This secret ritual opened the giant portal and blue light was shining from it. Aramu Muru entered the portal and has never been seen again. The gate got his name.