3,000-year-old Canaanite temple discovered in southern Israel

In southern central Israel, Tel Lachish’s new discovery consists of very rare inscriptions showing early precursors of Hebrew alphabet

In Tel Lachish National Park, the 3,000-year-old temple of Canaanite has unearthed by a team of Israelis and American archeologists.

Under the guidance of Prof. Yosef Garfinkel from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Prof. Michael Hasel from the University of southern Advent at Tennessee, the team published their findings in the Levant journal last month following years of excavations.

Located in south-central Israel, Tel Lachish is the site of the biblical Lachish, a major Canaanite city during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages that was later conquered by the Israelites. It was one of the only Canaanite cities to survive into the 12th century BCE.

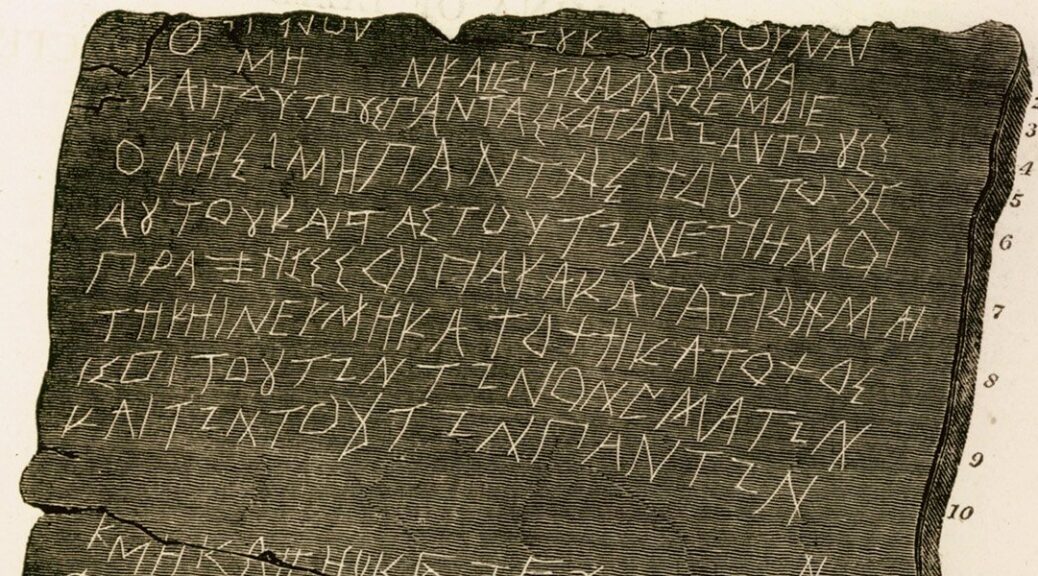

“We excavated a new temple in the northeast corner of the site that [dates] to the 12th century BCE,” Garfinkel told The Media Line. “It was extremely rich with objects and also [had] an inscription, which is very, very rare. The last time a Canaanite inscription was found was about 40 years ago.”

The aforementioned inscription was found on a pottery shard and features the oldest-known example of the letter “samekh.”

“Our inscription is Semitic: It’s Canaanite and later the Hebrew script developed from the same type of writing,” Garfinkel explained, adding that the discovery was “of tremendous importance to the history of the [Hebrew alphabet].”

The new temple marks the first time in a long while that a new Canaanite temple has been found; in fact, the majority of such structures were already unearthed in the early 20th century.

In addition, the Lachish temple was built in a symmetrical style which has only been seen in a few other places in Israel, among them Tel Megiddo, Hazor and Nablus.

“This is the first time that we have a symmetrical temple at Lachish,” Garfinkel said. “There are fewer than 10 of these in Israel.”

Itamar Weissbein, the lead co-author of the study and one of the excavators, told The Media Line that this is the third Canaanite temple found at Lachish.

The first two temples were discovered by a British expedition in the 1930s and an Israeli team in the 1970s, respectively.

“In general, temples in the ancient Near East were not like churches or synagogues that you [could] enter,” Weissbein said. “It’s a different type of cultic activity. Only a few elites – priests or maybe kings – entered to do some rituals there because it was a house of gods, not a house of worship in a way.”

Weissbein emphasized that worshippers would likely have been standing outside the temple in the courtyard, an area that has not been well-preserved over the centuries. Researchers were, however, able to glean some ideas about the cultic activities that took place inside the temple based on artifacts that they dug up.

“We found two figurines of male deities,” Weissbein stated. “They probably represent Baal, [who was] one of the main deities of the Canaanites, like a storm god or a fertility god … and another deity called Resheph, [who was] more of a warlike deity.”

In addition to the ruins, the figurines and the inscription, Garfinkel’s team also found bronze cauldrons, jewelry, daggers, scarabs and a gold-plated bottle bearing an inscription with the name of the powerful Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II.