Archaeologists discovered 1,700-year-old Roman eggs

In England, archeologists found a very rare discovery, but one that is very interesting. They found an approximately 1,700 years old unbroken egg dating back to the Roman Empire.

This remarkable finding is of importance as it provides insights into the beliefs and ritualist practices of Romans and Britons. It is the only complete egg ever discovered in the British Isles.

The discovery was found in the area of Berryfields housing and community development near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, by Oxford Archeology. The search was carried out for nine years.

Here they found “a middle Iron Age settlement and the agricultural hinterland of the putative nucleated Roman settlement of Fleet Marston” according to Oxford Archaeology.

This was situated on a major thoroughfare and was once an important trading, administrative, and agricultural center.

Down the years the archaeologists have uncovered many remarkable artifacts, dating from between the 1st century AD and the 4th century AD when the site was abandoned.

Among the items found were coins, pottery, and metal items. The Daily Mail reports that they all throw light on “Roman Fleet Marston which had previously only been understood from incidental finds”.

Archaeologists were working in the area, which is very waterlogged when they came across an unusual number of deposits in a pit. These were largely items that were organic in nature and they would typically have disintegrated over time.

Among the items that were recovered were leather shoes, wooden tools, and a wicker basket, which may have once held the bread.

The remains of an oak tree and wooden piles from a bridge were also unearthed from the waterlogged earth. Edward Biddulph, of Oxford Archaeology, stated that “the pit was still waterlogged, and this has preserved a remarkable collection of organic objects” according to the BBC.

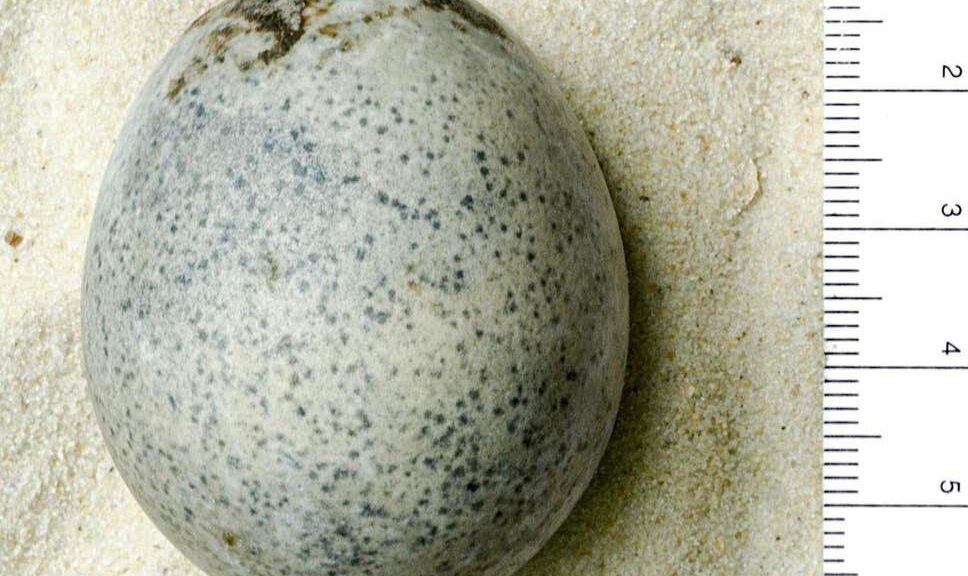

Among the organic items found were four eggs, that turned out to be chicken eggs. They were all found intact but as they were being moved, three of them broke, as they were so fragile.

The broken eggs emitted a very powerful and unpleasant smell, this was not a surprise as they were centuries old, after all.

However, one of the eggs was extracted intact from the muddy ground, after some painstaking work. This was astonishing as only fragments of eggshells had been found, previously in Britain, mainly from Roman-era graves.

The archaeologist had found the only complete chicken egg from Roman Britain. To find any intact egg from the past is very rare but to find one from 1,700 years ago is astonishing. The BBC reports that Mr. Biddulph said the discovery of the complete egg and other organic items “was more than could be foreseen”.

To understand why there were eggs and other items simply left in the ground we need to understand the area where they were found. It appears that the site was once a waterlogged pit, which was possibly used in a similar way to a wishing well.

People would toss objects into the pit for good luck. A Roman mirror and some pots had also been discovered in the location with the organic items.

It is also possible that the eggs and the basket, were offerings of food to the dead, possibly after a burial. This was very common in funerary customs in the classical era. Eggs were highly symbolic, for many ancient peoples and “In Roman society, eggs symbolized fertility and rebirth” according to the Daily Mail.

They were associated in particular with the Roman gods Mercury and Mithras, a deity of Persian origin. The eggs may have been placed in the pit to win the favor of one of these gods.

The excavation was financed by the construction company, Berryfields Consortium. The dig finished in 2016 and for the past three years, researchers have been carefully analyzing the numerous finds.

A monograph that “describes the results of the fieldwork and analysis of an exceptional range of the artifactual and environmental evidence” reports Oxford Archaeology was published this year.