Denny, a mysterious child from 90,000 years ago, whose parents were two different human species

More than 90,000 years back in time, a unique child was walking the Earth. This individual was a young human hybrid. Scientists dubbed the ancient girl “Denny,” the only known individual whose parents were from two distinct human species!

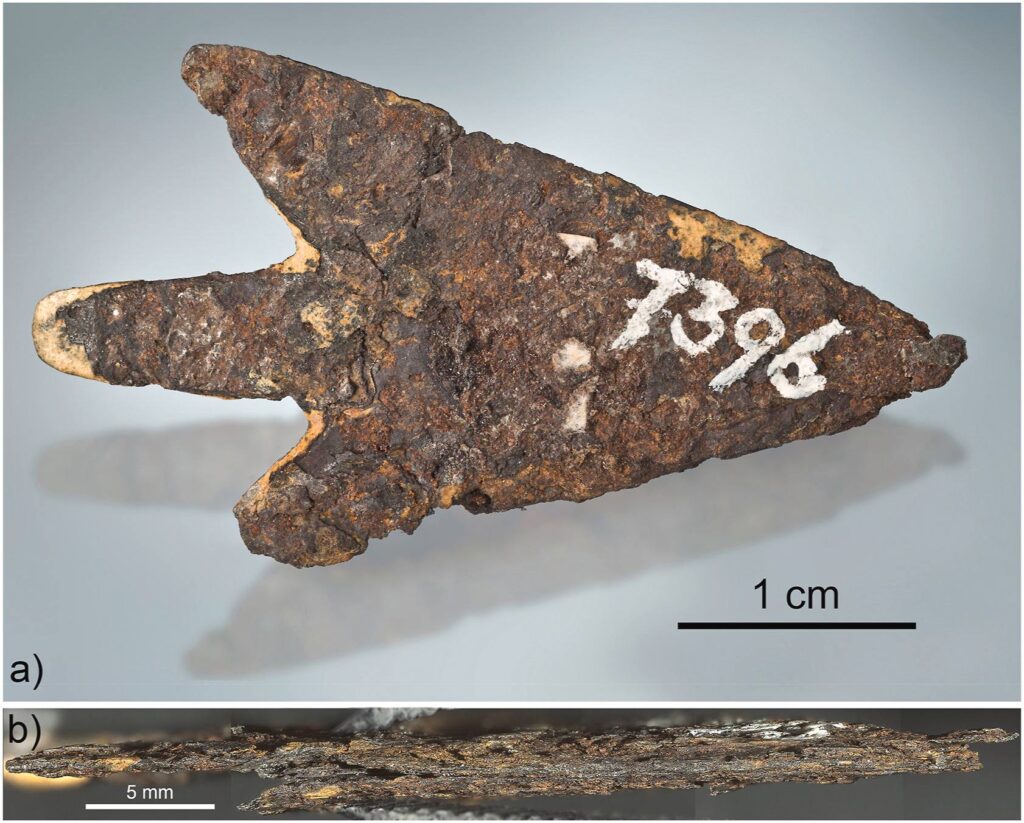

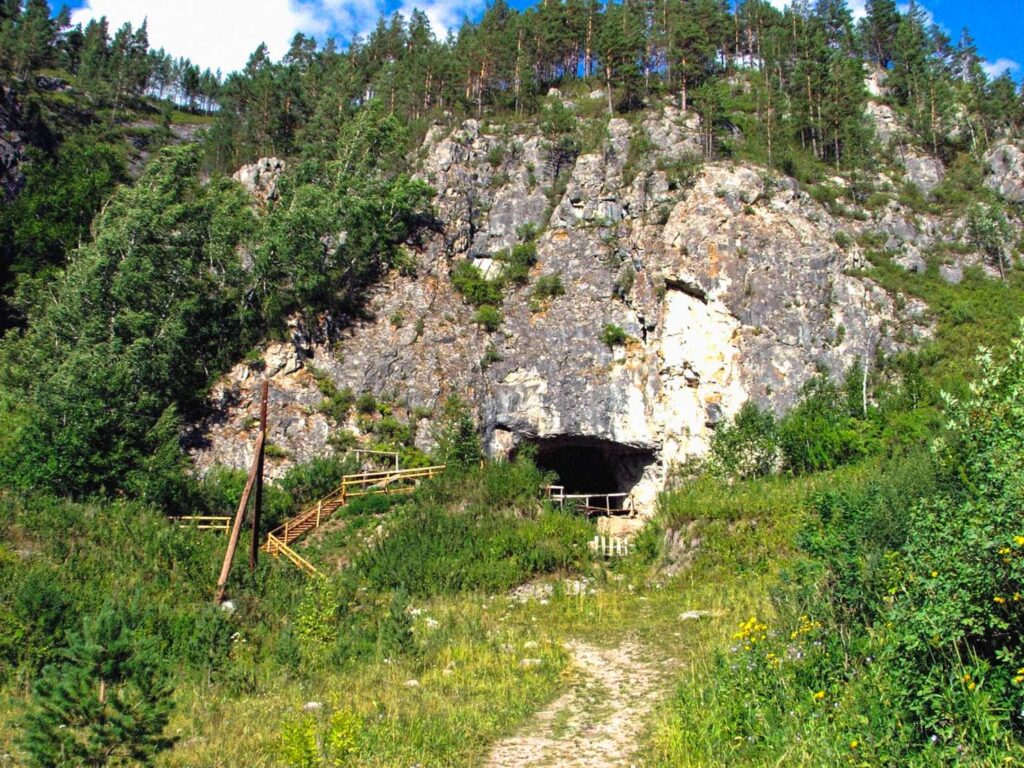

In 2018, researchers looking into Denisova Cave in the Altai mountains of Siberia located the skeletal remains of the Denny. With only a bone and teeth to work with, researchers were still able to identify who the individual was.

A new effort, called FINDER, has been launched to explore the Denisovans and the relationships between them, Homo sapiens, and the Neanderthals.

The purpose of the investigation is to gain a further understanding of the interaction between the three species. It is known that the three species interbred, but the study aims to provide further detail of the connections between them.

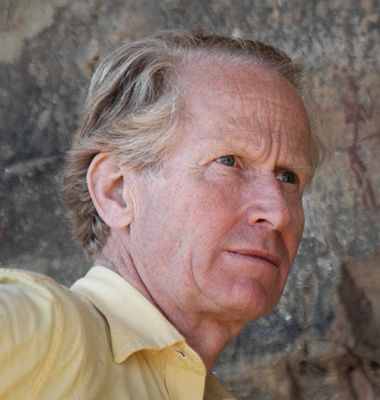

The purpose of the project, led by Katerina Douka of the Max Planck Institute in Jena, Germany, and a visitor at Oxford University, is to identify where Neanderthals lived when they interacted with Homo sapiens, and why they eventually went extinct.

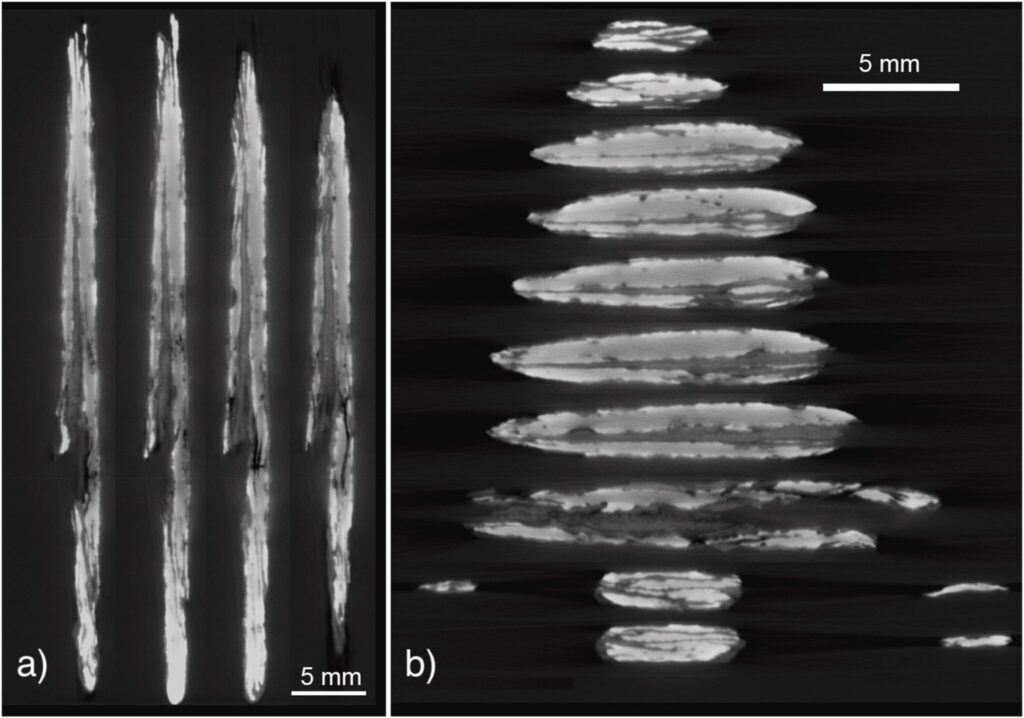

Studying the history of the Denisovans is difficult due to the fact that the only archaeological site that has yielded their fossils is the Denisovan Cave in Siberia. Moreover, only a few fossils have been unearthed from this site, along with some Neanderthal specimens.

Tom Higham, the deputy director of Oxford University’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit and an advisor to Finder, remarks on how great the site is. He states that it is nice and cool inside, thus preserving the DNA in the bones. Unfortunately, he goes on to add that the majority of the bones in the cave were destroyed by hyenas and other carnivores, leaving a mess of tiny, unrecognizable bone fragments scattered across the floor.

Higham states that it is not possible to distinguish between the source of a piece of material, be it from a mammoth, sheep, man, or woman, without a thorough examination. He further explains that even if only a handful of finds are from humans, they are of great value as they provide a great deal of knowledge.

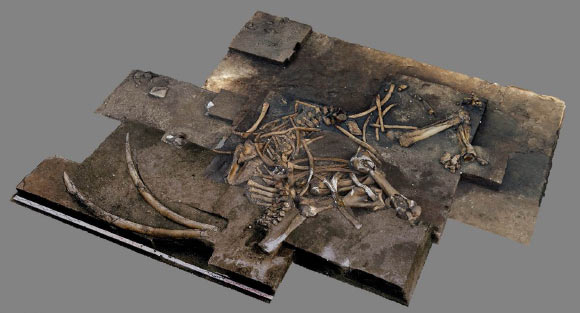

DNA sequencing of the ancient girl’s bones revealed her to be a product of two distinct species. Her mother was Neanderthal, and her father was a Denisovan. Denny had been living with various Neanderthals and Denisovans in the cave when she tragically passed away at a young age.

It is believed that Neanderthals and Denisovans separated from each other at least 390,000 years ago, making them both now extinct groups of hominins.

Analysis of the genome of ‘Denisova 11’ – a bone fragment from the Denisova Cave located in Russia – reveals that the individual had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. The father’s genome displays Neanderthal ancestry, belonging to a population linked to a later Denisovan from the cave.

The mother came from a population that is more closely connected to Neanderthals that lived in Europe than to the earlier Neanderthal discovered in Denisova Cave, indicating that migrations between eastern and western Eurasia of Neanderthals happened sometime after 120,000 years ago.

The new study published in the journal Nature indicates that interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans was more common than previously assumed, considering the small number of archaic samples that have been sequenced.

It could be assumed that the extraordinary lineage of Denny suggests that Neanderthals and Denisovans were often engaging in interbreeding, though researchers caution against forming such speculations hastily.

It is evident that the DNA of Neanderthals and Denisovans are different, making it easy to distinguish between them. According to Douka, this suggests that interbreeding between the two did not occur frequently, as otherwise, their DNA would be similar.

It has been demonstrated by prior research that Denisovans and Homo sapiens interbred, yet the question of why this happened at Denisova is still unanswered.

It has been proposed that the cave could be seen as a border crossing for the two species, with the Neanderthals mostly located in Europe and the Denisovans in the east. Periodically, both species would find themselves in the cave at the same time, which could have led to relations between the two.

Detailed studies of Denny’s Neanderthal mom revealed that her genes had a special connection to Neanderthals in Croatia, which suggests that the predecessors of her mother may have been part of a group migrating east from Europe to Denisova – where she and Denny’s father met at the boundaries of their respective homelands.

This is a captivating image, yet more data is needed to authenticate it. Researchers don’t have direct proof that the Denisovans were mainly situated in the east of the cave, notwithstanding, the fact that their genetic material has been identified in the DNA of people in Australia, New Guinea, and different parts of Oceania, reinforces this concept and implies that future investigations for sites should be focused on eastern Russia, China, and south-east Asia.

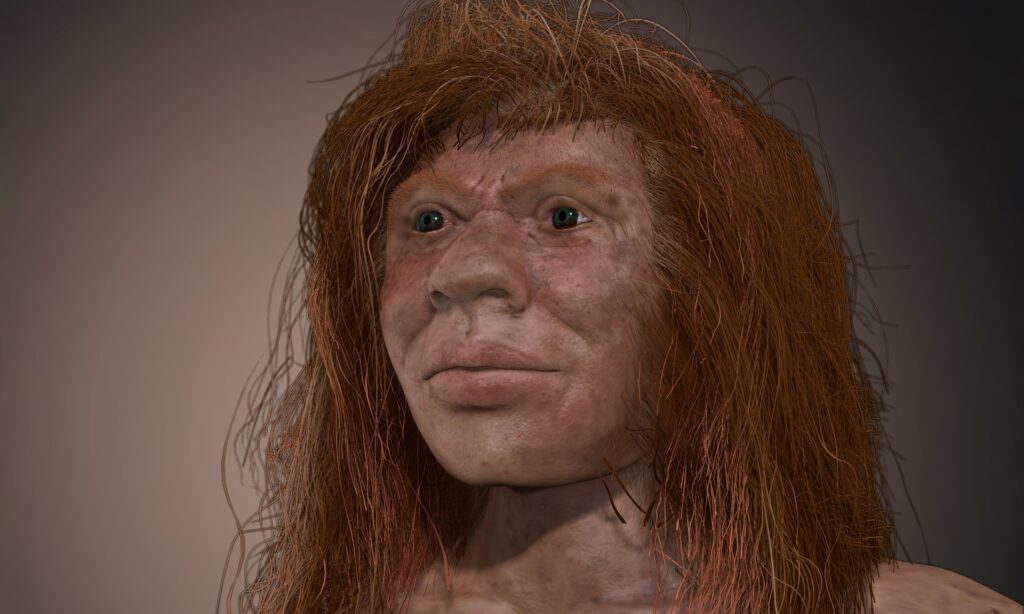

Though scientists have limited knowledge about the extinct human species known as the Denisovans, experts have recently been able to construct the inaugural facial reconstruction to provide an image of what they may have looked like. This has enabled people to see a vision of what the Denisovans may have appeared to be.

Higham mentions that researchers have numerous inquiries they have yet to answer. For instance, where did the Denisovans extend to, and what is the earliest proof for their divergence from the common ancestor they had with Neanderthals 500,000 years ago?

It may take some time before scientists can locate a bone or two from different areas, but the potential benefits would be worth the wait.