Orichalcum, the lost metal of Atlantis, may have been found in a shipwreck off Sicily

MYSTERIOUS metal ingots linked to the mythical civilisation of Atlantis have been recovered from an ancient shipwreck off the coast of Sicily.

Archaeologists last month recovered a wealth of ingots of an unusual golden alloy from the wreck sitting in about 3m of water, 300m off the coast of Gela in southern Sicily.

Also recovered from the wreck, which sank some 2600 years ago, were two Corinthian war helmets and containers once used to hold precious, scented oils.

But it is the rough lumps of metal still shining with red and gold hues after two millennia on the sea floor that has excited the archaeological world.

It could be orichalcum.

The mythical lost metal of Atlantis.

But, in 2014, the metal returned to reality with the discovery of the wreck off Sicily. In 2015, 39 roughly-cast lumps of an unusual red-gold metal were recovered from the sea floor.

Divers uncovered another 47 ingots from the mud last month.

SO CLOSE, YET SO FAR

The archaeologists working on recovering the wreck say it went down within sight of safety.

“The ship dates to the end of the sixth century BC,” Sicilian archaeologist Sebastiano Tusa told Seeker.

“It was likely caught in a sudden storm and sunk just when it was about to enter the port.”

This rules out Atlantis. Plato, writing in the 4th Century BC, implies that the legendary city slipped beneath the waves many hundreds — perhaps thousands — of years earlier. Archaeologists believe the ship was exporting the orichalcum from Greece or Asia Minor.

Given its precious cargo, it may not have had an easy voyage.

“The presence of helmets and weapons aboard ships is rather common. They were used against pirate incursions,” Tusa said.

Also recovered was an anchor, remains of amphorae and several smaller containers used for carrying precious oils. The shipwreck, and that of another two nearby, are yet to be fully excavated. Tusa told La Repubblica that protecting the wrecks remains a concern, with looters believed to be exploiting a lack of policing of the archaeologically rich waters.

MYTHICAL METAL

The red-hued orichalcum alloy was long regarded to be a myth mentioned only in passing in Ancient Greek tales by the likes of Hesiod in the 8th Century BC and Plato in the 4th Century BC. One legend states it was invented by the legendary first king of Thebes, Cadmus, and was said to be regarded as being only slightly less precious than gold.

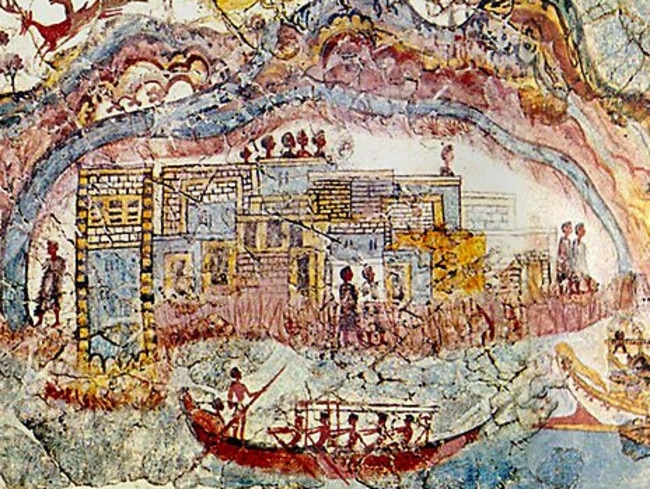

Plato lauded the glistening metal’s properties, and attributed it to Atlantis:

“For because of the greatness of their empire many things were brought to them from foreign countries, and the island itself provided most of what was required by them for the uses of life. In the first place, they dug out of the earth whatever was to be found there, solid as well as fusile, and that which is now only a name and was then something more than a name, orichalcum, was dug out of the earth in many parts of the island, being more precious in those days than anything except gold.”

He went on to say the metal was used to give the interior of the temple of Poseidon, at the heart of Atlantis, a magical glow.

“The zones of earth were surrounded by stone walls of divers colours, black and white and red, which they sometimes intermingled for the sake of ornament; the outermost wall was coated with brass, the second with tin, and the third, which was the wall of the citadel, flashed with the red light of orichalcum.”

Exactly what it was, and what it was made of, was a matter of speculation.

FROM LEGEND TO REALITY

Turns out, orichalcum may not be as exotic as the ancient tales suggest. Though it was almost certainly mysterious to many of the jewellers who formed it — and sold it.

Studies have shown the metal ingots to be made of about 75-80 per cent copper, 14-20 per cent zinc and a scattering of nickel, lead and iron.

The process of its production was likely to have been a tightly-held secret. Exactly how it was achieved remains a matter of debate.

One explanation that fits the findings is that zinc ore, charcoal and copper could have been reacted in a molten crucible.

Whatever the case, the shiny brass-like alloy was highly regarded as it did not tarnish. It was also durable enough for use in jewellery.

Which is where the shipwreck comes in.

It was found just outside a harbour to the Greek colony city of Ghelas which, in ancient times, was a centre for craftsmen specialising in fine jewellery and ornate artefacts.