A rare Elizabethan ship discovered at quarry 300 meters from the coast

In April 2022, a team from CEMEX unexpectedly uncovered the remains of a rare Elizabethan-era ship, while dredging for aggregates at a quarry on the Dungeness headland, in Kent.

Found some 300 metres from the coast, the discovery stumped the quarry team, who contacted our experts to study the remains. Recognising the significance of this extraordinary discovery, Kent County Council enlisted specialist support and emergency funding from Historic England.

The story of this rare Elizabethan ship will feature on Digging for Britain on BBC2 at 8pm on 1 January 2023.

Very few English-built 16th-century vessels survive, making this a rare discovery from what was a fascinating period in the history of seafaring.

The late 16th-century was a period of great expansion of trade, with the English Channel serving as a major route on Europe’s Atlantic seaboard.

Although the ship remains unidentified, it represents an era when English vessels and ports played an important role in this busy traffic.

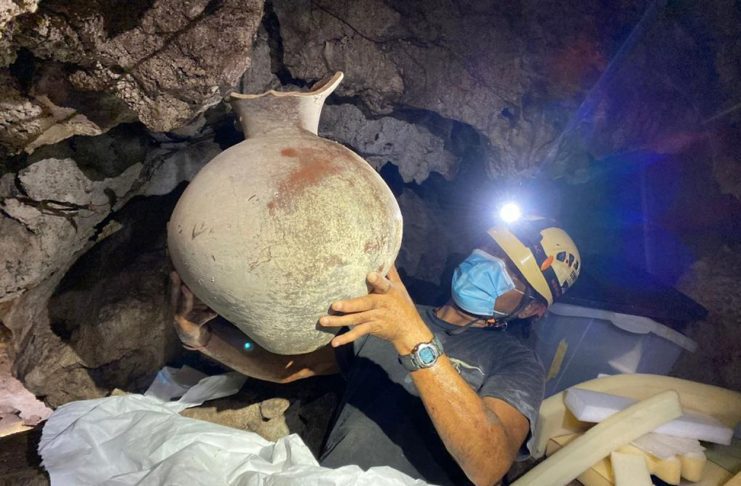

Above: Archaeologist records the ship’s remains on-site (Left). The hull of the 16th-century ship remains at the quarry (Right).

Over 100 timbers from the ship’s hull were recovered, with dendrochronological analysis, funded by Historic England, dating the timbers that built the ship to between 1558 and 1580 and confirming it was made of English oak.

This places the ship at a transitional period in Northern European ship construction. When ships are believed to have moved from a traditional clinker construction (as seen in Viking vessels) to frame-first-built ships (as recorded here), where the internal framing is built first and flush-laid planking is later added to the frames to create a smooth outer hull.

This technique is similar to what was used on the Mary Rose, built between 1509 and 1511, and the ships that would explore and settle along the Atlantic coastlines of the New World.

Above: Archaeologist records the ship’s remains on-site.

Andrea Hamel, Marine Archaeologist at Wessex Archaeology, said: “To find a late 16th-century ship preserved in the sediment of a quarry was an unexpected but very welcome find indeed.

The ship has the potential to tell us so much about a period where we have little surviving evidence of shipbuilding but yet was such a great period of change in ship construction and seafaring.”

Although uncovered 300 metres from the sea in what is today a quarry, experts believe the site would have once been on the coastline, and that the ship either wrecked on the shingle headland or was discarded at the end of its useful life. Its discovery presents a fascinating opportunity to understand the development of the coast, ports and shipping of this stretch of the Kent coast.

Antony Firth, Head of Marine Heritage Strategy at Historic England, said: “The remains of this ship are really significant, helping us to understand not only the vessel itself but the wider landscape of shipbuilding and trade in this dynamic period.

CEMEX staff deserve our thanks for recognising that this unexpected discovery is something special and for seeking archaeological assistance.

Historic England has been very pleased to support the emergency work by Kent County Council and Wessex Archaeology, and to see the results shared in the new season of Digging for Britain.”

Our archaeologists have recorded the ship using laser scanning and digital photography. Once our work is complete the timbers will be reburied in the quarry lake where they were uncovered so that the silt can continue to preserve the remains.