Genetic Study Tracks Warriors from Mongolia to Hungary

Less known than Attila’s Huns, the Avars were their more successful successors. They ruled much of Central and Eastern Europe for almost 250 years. We know that they came from Central Asia in the sixth century CE, but ancient authors, as well as modern historians, have long debated their provenance.

Now, a multidisciplinary research team of geneticists, archaeologists and historians, including researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, obtained and studied the first ancient genomes from the most important Avar elite sites discovered in contemporary Hungary.

This study traces the genetic origin of the Avar elite to a faraway region of East-Central Asia. It provides direct genetic evidence for one of the largest and most rapid long-distance migrations in ancient human history.

In the 560s, the Avars established an empire that lasted more than 200 years, centered in the Carpathian Basin. Despite much scholarly debate their initial homeland and origin have remained unclear.

They are primarily known from historical sources of their enemies, the Byzantines, who wondered about the origin of the fearsome Avar warriors after their sudden appearance in Europe. Had they come from the Rouran empire in the Mongolian steppe (which had just been destroyed by the Turks), or should one believe the Turks who strongly disputed such a legacy?

Historians have wondered whether that was a well-organized migrant group or a mixed band of fugitives. Archaeological research has pointed to many parallels between the Carpathian Basin and Eurasian nomadic artifacts (weapons, vessels, horse harnesses), for instance, a lunula-shaped pectoral of gold used as a symbol of power. We also know that the Avars introduced the stirrup in Europe. Yet we have so far not been able to trace their origin in the wide Eurasian steppes.

In this study, a multidisciplinary team—including researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, the ELTE University and the Institute of Archaeogenomics of Budapest, Harvard Medical School in Boston, the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton—analyzed 66 individuals from the Carpathian Basin.

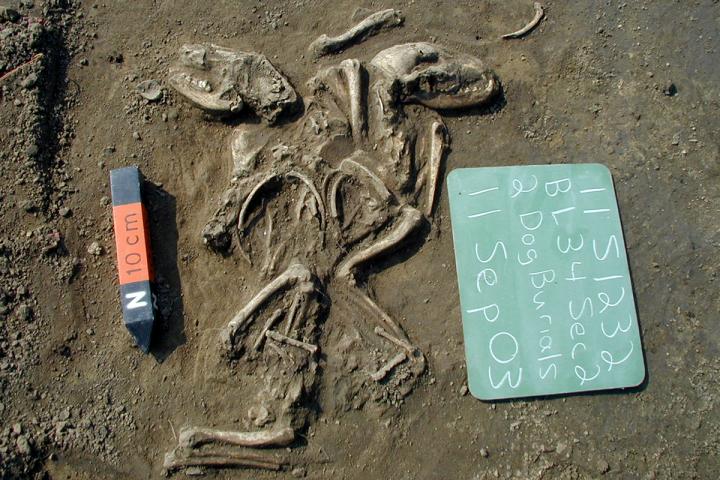

The study included the eight richest Avar graves ever discovered, overflowing with golden objects, as well as other individuals from the region prior to and during the Avar age.

“We address a question that has been a mystery for more than 1400 years: who were the Avar elites, mysterious founders of an empire that almost crushed Constantinople and for more than 200 years ruled the lands of modern-day Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Austria, Croatia and Serbia?” explains Johannes Krause, senior author of the study.

Fastest long-distance migration in human history

The Avars did not leave written records about their history and these first genome-wide data provide robust clues about their origins.

“The historical contextualization of the archaeogenetic results allowed us to narrow down the timing of the proposed Avar migration.

They covered more than 5000 kilometres in a few years from Mongolia to the Caucasus, and after ten more years settled in what is now Hungary. This is the fastest long-distance migration in human history that we can reconstruct up to this point,” explains Choongwon Jeong, co-senior author of the study.

Guido Gnecchi-Ruscone, the lead author of the study, adds that “besides their clear affinity to Northeast Asia and their likely origin due to the fall of the Rouran Empire, we also see that the 7th-century Avar period elites show 20 to 30 per cent of additional non-local ancestry, likely associated with the North Caucasus and the Western Asian Steppe, which could suggest further migration from the Steppe after their arrival in the 6th century.”

The East Asian ancestry is found in individuals from several sites in the core settlement area between the Danube and Tisza rivers in modern-day central Hungary.

However, outside the primary settlement region, we find high variability in inter-individual levels of admixture, especially in the south-Hungarian site of Kölked. This suggests an immigrant Avars elite ruling a diverse population with the help of a heterogeneous local elite.

These exciting results show how much potential there is in the unprecedented collaboration between geneticists, archaeologists, historians and anthropologists for the research on the “Migration period” in the first millennium CE. The research was published in Cell.