Last meal of a man mummified in a bog reconstructed after 2400 years

The Tollund Man is one of the most famous ‘bog bodies’ ever discovered in northern Europe. Even though the 30- to 40-year-old human was buried in a bog more than 2,400 years ago, the acidic peat has mummified his body to a remarkable degree, preserving his hair, brain, skin, nails, and intestines – even the leather noose around his neck.

Despite all the evidence, we still don’t really know why he was killed. An updated analysis of the man’s gut has now revealed all the contents of his last meal, and it’s looking more and more like he was some sort of human sacrifice.

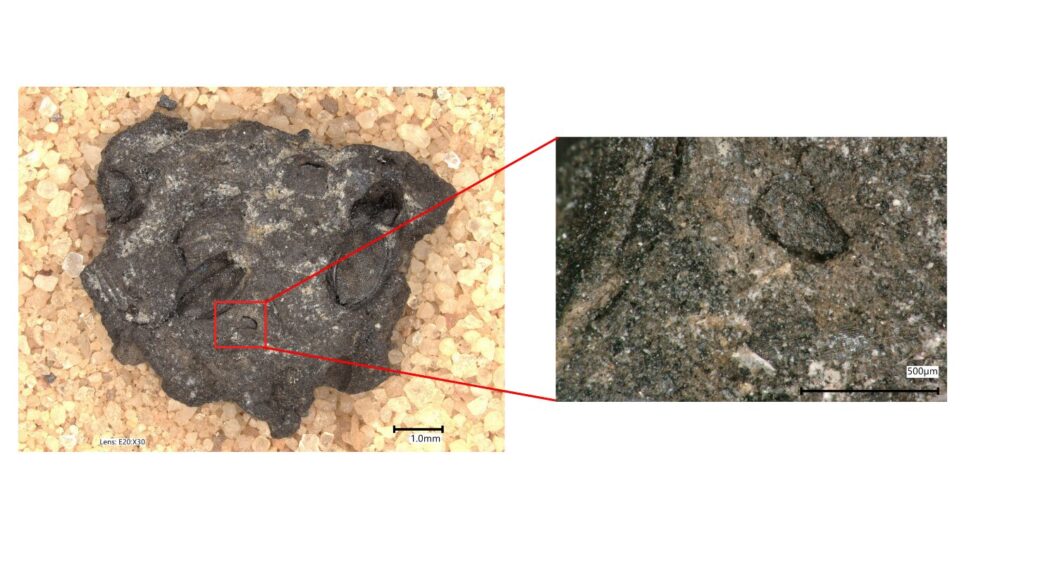

Roughly a day before the Tollund Man was hung and buried in the bog, researchers say he ate porridge, containing barley, flax, and seeds from plants and weeds.

That’s similar to what scientists found in the early 1950s when the body was first unearthed in what is now modern Denmark. But unlike past analyses, this one has also noticed a few new ingredients, like the fatty proteins of fish as well as remnants of threshing waste, which comes from separating grain.

That’s an intriguing discovery, as a recent analysis of another bog body, known as the Grauballe Man, has also turned up a surprisingly large quantity of threshing waste not noticed before.

The Grauballe Man was also killed and buried in an acidic bog, and the similar contents of his last meal to the Tollund Man’s last meal may indicate a ritual of sorts.

While other bog bodies appear to have eaten porridge or bread with a side of meat or berries, threshing waste and an abundance of seeds might indicate a special occasion. Either that, or these ingredients were simply added for flavor or nutrition.

“Although the meal may reflect ordinary Iron Age fare, the inclusion of threshing waste could possibly relate to ritual practices,” the authors write.

This isn’t the first time the Tollund Man or the Grauballe Man have been suspected victims of sacrifice.

While other bog bodies found might have fallen dead or drowned in the peat by accident, the way the Tollund Man was killed and then carefully buried, with his eyes and mouth closed shut and his body in a fetal position, has some scientists thinking he was a sacrifice to the gods.

Considering that the Tollund Man was buried near a place where Iron Age people used to dig for peat, it’s possible his body represented a form of gratitude for the land.

Some Roman historian accounts from the time have even written about similar human sacrifices in northwestern Europe, although these were often biased reports that might have stretched the truth about certain tribes.

Apart from the way in which the Tollund Man was buried, his gut is one of the juiciest clues we have. Further research will be needed to determine whether other bog bodies also ate meals containing threshing waste or seeds, or if these were, in fact, special ingredients given to humans before they were sacrificed.

The Tollund Man may be long dead, but his mystery continues to live on.