5700-year-old child skeleton unearthed in the Turkish city of Malatya

A 5,700-year-old skeleton of a noble-born child has been found buried in the ruins of a Copper Age Turkish house. Anthropologists believe the bones belonged to a six-year-old who most likely died of trauma in the fourth millennium BC.

The skeleton was found in the foetal position and the skull has been smashed, although it’s not immediately clear whether this happened before or after death.

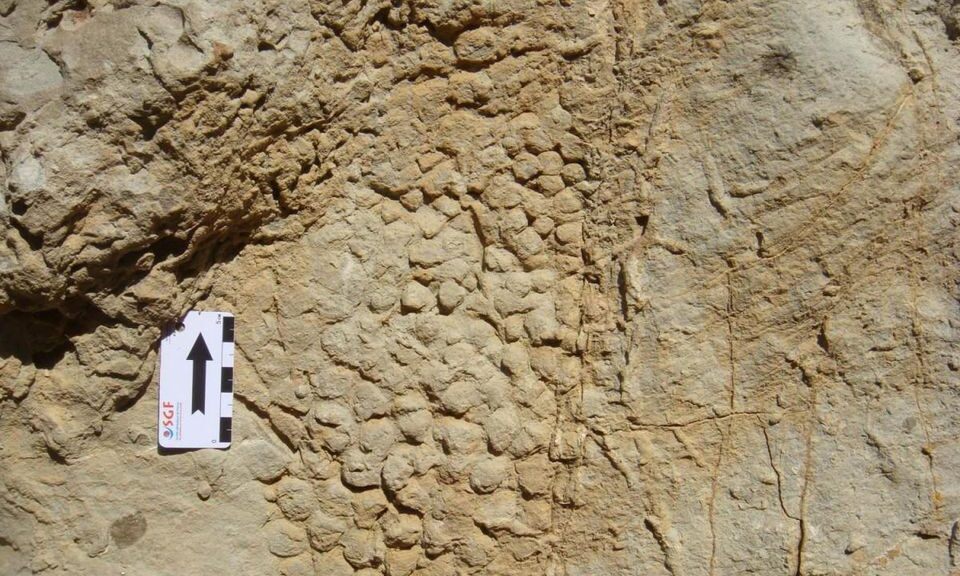

The remains were found in what is believed to be an ancient house during an excavation of the Arslantepe Mound outside Malatya, eastern Turkey.

With its prime position near the west bank of the Euphrates River, this UNESCO World Heritage site boasted a thriving population through the Roman and Byzantine periods owing to its wetlands and agricultural resources.

Yet now it is flocked to by archaeologists who comb through the ruins hoping to learn more about Arslantepe’s rich history.

Dr Marcelle Frangipane, of the University of Rome who led the dig, said the bones would be sent for analysis but early estimates suggested the child was very young and died of shock.

She said: ‘We found beads on the arms and neck of the child, which we have not seen before. These beads indicate that the child belonged to a noble family.’

Hailing the skeleton an ‘important find’, she added: ‘The delegation stated that the child is six or seven years old, but they need to work on it further.

‘The child may have died as a result of trauma. Such results will be determined as a result of the analysis.

‘This is a very important find. As a result of the analysis of the skeleton, we will reach more detailed information.’

Dr Frangipane also said that they are waiting for the results of the examination to discover the gender, genetic structure, age and cause of death of the child as well as the diet of the era.

The position of the skeleton suggests the child was frightened and had curled itself into the foetal position, wrapping its arms around its body.

Remarkably, the position which this infant died in has been almost perfectly preserved in the ground, although its skull has been caved in.

Over the past 50 years, since serious excavations of the Arslantepe Mound began, archaeologists are slowly unearthing what they believe to be a fourth millennium BC palace.

Interconnected mud-brick architecture sprawling over 2,000 square metres is suggestive of the first ‘public palace’, according to UNESCO.

The organisation says this ancient structure was ‘composed by two temples, a storeroom complex, administrative areas with thousands of clay-ceilings bearing the impressions of more than 220 beautiful seals, entertainment halls, a monumental gate, corridors and courtyards.