Broken toilet leads to the discovery of 2,000 years of history beneath the Italian restaurant

A blocked toilet in an Italian building has changed the life of its owner who was planning to open a trattoria on the site. Lucian Faggiano was trying to find the offending sewage pipe at the property in Puglia, Italy when he made a fascinating discovery.

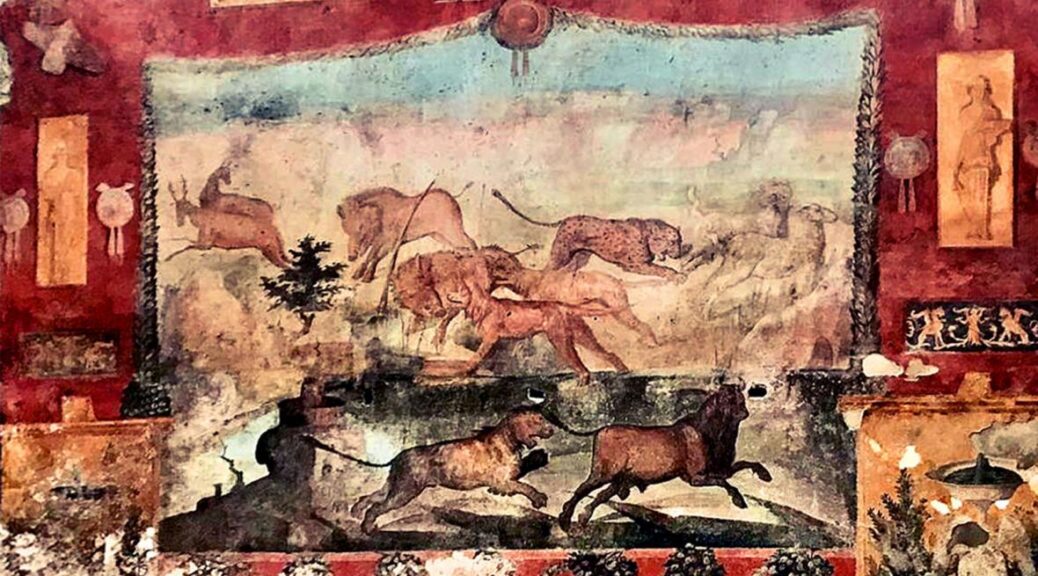

After digging a trench beneath the building he found a network of underground rooms and corridors that housed Roman devotional bottles, ancient vases, hidden frescoes and what are thought to be etchings from the Knights Templar.

Lucian Faggiano bought the building in Lecce, Puglia in the south of Italy and had planned to turn it into a trattoria – but renovations were put on hold when he discovered a toilet on the site was blocked.

And while attempting to fix the toilet he dug into a Messapian tomb built 2,000 years ago, a Roman granary, a Franciscan chapel, and even etchings thought to be made by the Knights Templar.

In a bid to stop the sewage backing up, Mr Faggiano, 60, and his two sons dug a trench and instead of isolating the offending pipe found underground corridors and rooms beneath the property on 56 Via Ascanio Grandi.

The search for the pipe began at the turn of the millennium.

Lecce, at the heel of Italy’s boot’, was once a crossroads in the Mediterranean and an important trading post for the Romans. But the first layers of the city date to the time of Homer, according to local historian Mario De Marco. It is not unusual for religious relics to turn up in fields or in the middle of the city itself, which has a mixture of old architecture

For example, a century ago, a Roman amphitheatre was recently found beneath a marble column bearing the statue of Lecce’s patron saint, Orontius in the main square and recently a Roman temple was found under a car park.

‘Whenever you dig a hole, centuries of history come out,’ said Severo Martini, a member of the City Council. Mr Faggiano asked his sons to help fix the problem with the plumbing so he could accelerate the opening of his restaurant, in a building that looked like it was modernised.

But when they dug down they hit a floor of medieval stone, beneath which was a Messapian tomb, built by people who lived in the area before the birth of Jesus. Legend has it the city was founded by the Messapii, who are said to have been Cretans in Greek records, but then the settlement was called Sybar.

Upon further investigation, the family team also discovered a Roman room that was used to store grain and a basement of a Franciscan convent where nuns were thought to have once prepared the bodies of the dead.

Afraid of costs and the delay in opening the restaurant, Mr Faggiano initially kept his amateur archaeology a secret from his wife, in part perhaps because he was lowering his youngest son, Davide, 12 though small gaps in the floor to aid his work.

But his wife, Anna Maria Sanò suspected the work was more complex than it appeared thanks to the number of dirty clothes she was washing, and because of dirt and debris is taken away.

Investigators shut down the site, warning Mr Faggiano he was conducting an unofficial archaeological dig. After a year, work continued but had to be overseen by heritage officials who witnessed the emergence of Roman devotional bottles, ancient vases and a ring with Christian symbols as well as hidden frescoes and medieval pieces.

Retired cultural heritage official, Giovanni Giangreco, who was involved with the excavation, said: ‘The Faggiano house has layers that are representative of almost all of the city’s history, from the Messapians to the Romans, from the medieval to the Byzantine time.’

Despite bearing the financial load of the dig, the family became fascinated about the history beneath their building and made ends meet by renting rooms in it. Mr Faggiano admits to becoming obsessed with the project but still wanted to open his restaurant.

He said: ‘At one point, I couldn’t take it anymore I bought cinder blocks and was going to cover it up and pretend it had never happened.’

Eight years after it was meant to open as a restaurant, the incredible building has been turned into Museum Faggiano and a number of staircases allow visitors to travel down through time to visit the ancient underground chambers.

However, Mr Faggiano hasn’t given up on his culinary dream and is planning on opening a restaurant at a less complex location – even though he finally found the troublesome sewage pipe.