Burials of Africans slaves found at the old rubbish dump in Portugal

Portuguese explorers such as Henry the Navigator started sailing to Africa in the early 15th century, bringing both goods and enslaved people back.

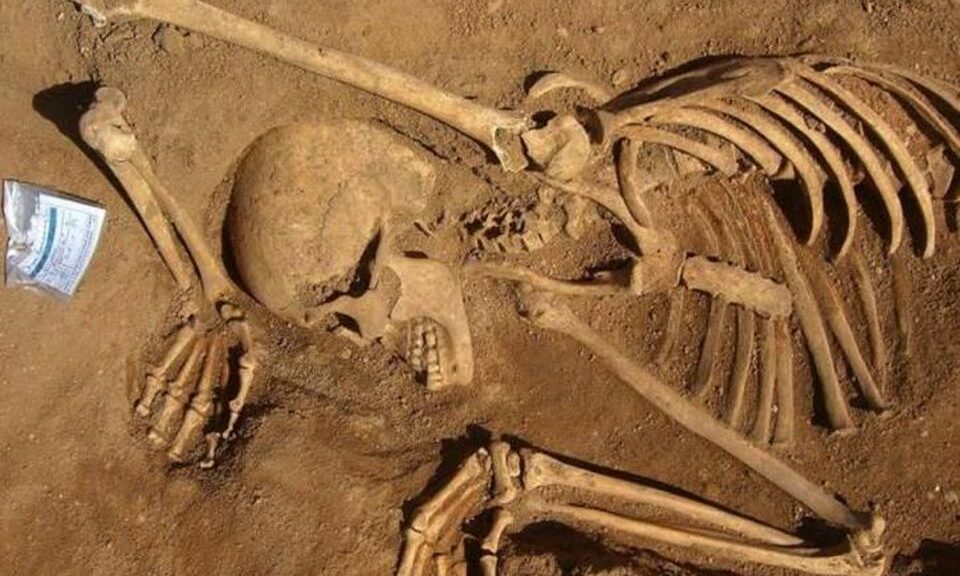

A new archeological study of more than 150 skeletons dumped in Lagos, Portugal, reveals that there were no proper burials given to many of the enslaved Africans and that several of them may even have been tied to death.

The skeletons come from the site of Valle da Gafaria, which was located outside the Medieval walls of the port city of Lagos along the southwest coast of Portugal. Used between the Fifteenth and Seventeenth centuries as a dumping ground, the site also offered up remains of imported ceramics, butchered animal bones, and a few African style ornaments.

When the human skeletons were first analyzed, their shape and unique dental style suggested that they might have been of African origin, and subsequently, genetic analysis confirmed ancestry with Bantu – speaking populations of South Africa. Due to the archaeological and historical information, it is likely that all of these people were enslaved.

In a new research article published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Maria Teresa Ferreira, Catarina Coelho, and Sofia Wasterlain of the University of Coimbra dug further into the bone data in order to understand how the 158 enslaved Africans came to be buried in a trash pit in Lagos.

Specifically, they investigated the position of each burial, whether or not the burial was made with care, and whether they could identify any evidence that the person’s body had been bound.

The Medieval Catholic concern with burial meant that the church was important in handling deaths in Portugal. A body would be ferried to the church in a funeral procession, and a grave would be chosen as close to a religious building as possible.

Elites and nobles were usually buried in an area protected by walls, while more marginal people were located outside. Those people who were further stigmatized by disease, condemned, or otherwise considered not to be deserving of care would be placed far outside sacred spaces.

Enslaved occupants of Medieval Portugal would not necessarily have been prevented from a proper burial. Many were baptized on arrival to Portugal and therefore had a right to a Christian funeral if the slave owner decided to do so.

However, due to the poor conditions aboard the ships, many people arrived so weakened that they died without being baptized. “In such cases,” Ferreira and colleagues explain, “as their humanity was not recognized, the corpses were treated as animal remains: summarily buried in any free field or dumped in the garbage.”

More than half of the people “seemed to have been buried without care,” Ferreira and colleagues note. “Moreover, six individuals showed evidence of having been tied when inhumed.” This suggests that several people had been tied up has intrigued other scholars, although it is unclear from the published research whether the bound limbs were related to the people’s enslaved status or to a more functional method of disposing of bodies.

Biological anthropologist Tim Thompson at Teesside University praised the “sound research” but also told me that “it is difficult to truly assess the examples of tied individuals because there are so few, and no figures are presented.” He suggests that comparing “the anatomical positioning with examples from modern mass graves would allow for deeper analysis. There are many examples of binding and blindfolding in these modern mass violence settings, along with disrespectful deposition of bodies.”

Ellen Chapman, a bioarchaeologist and cultural resources specialist at Cultural Heritage Partners, also told me that she looks forward to further work on this site and this collection of skeletons because “this site is an incredibly disturbing one, and one that clearly illustrates the pervasive mistreatment of enslaved people by the architects of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.”

In particular, Chapman notes that “this skeletal collection is indicative of the high mortality associated with slave ships and the Middle Passage.” Thompson adds that “this work has the potential to contribute to our understanding of both ancient and modern forced slavery contexts.”

In the end, Ferreira and colleagues conclude that “Valle da Gafaria’s osteological collection is extremely important for slavery studies. Not only are there few cemeteries of enslaved people in the world, but also, Lagos is the oldest sample to be discovered and studied in the world.”

Source: archaeologynewsnetwork