Intact Ball Game Carving Discovered at Chichen Itza

*** Presents two ball players in the center; It has a diameter of 32.5 centimeters, 9.5 centimeters thick, and 40 kilograms in weight.

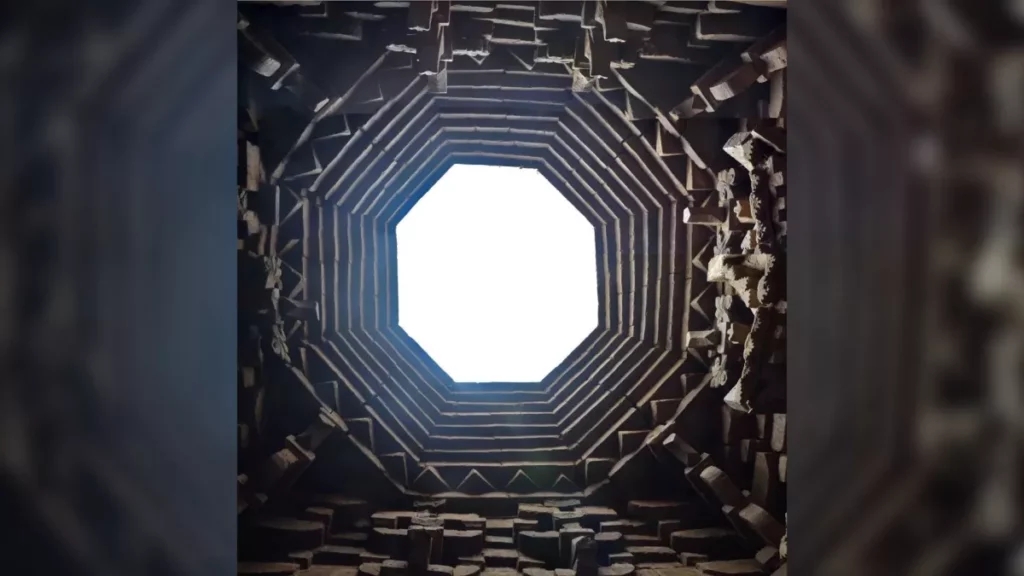

*** It must have been attached to an arch that served as access to the Casa Colorada architectural complex

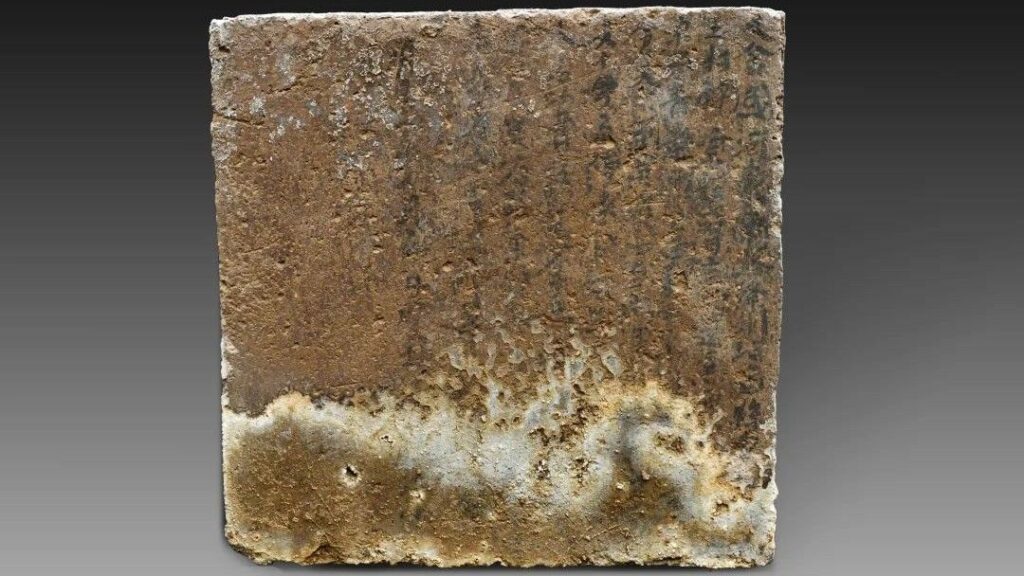

In the Archaeological Zone of Chichén Itzá, archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) discovered a stone marker of the Ball Game in a circular shape, which presents a bas-relief glyphic band surrounding two attired characters like ball players.

The relevance of the finding lies in the fact that it is a sculptural element that preserves its complete glyphic text.

With 32.5 centimeters in diameter, 9.5 centimeters thick, and 40 kilograms in weight, the piece was found during archaeological work carried out as part of the Program for the Improvement of Archaeological Zones (Promeza), in charge of the Federal Ministry of Culture.

The piece, named Ball Players Disc, was found by archaeologist Lizbeth Beatriz Mendicuti Pérez, within the Casa Colorada architectural complex (named after the remains of red paint inside) or Chichanchob ─located between the Ossuary and the Observatory─, as part of Structure 3C27, which corresponds to an access arch to the area, informed the archaeologist Francisco Pérez Ruiz, who together with the archaeologist José Osorio León coordinates the execution of the Promise in Chichén Itzá.

“In this Mayan site it is rare to find hieroglyphic writing, let alone a complete text; It hasn’t happened for more than 11 years,” said archaeologist Pérez Ruiz, explaining that the monument found functioned as a marker of some important event related to the Casa Colorada Ball Game, a court much smaller than the Great Game of Chichen Itza ball.

The researcher estimates that this Ball Game marker must correspond to the Terminal Classic or Early Postclassic period, between the end of the 800s and the beginning of 900 AD.

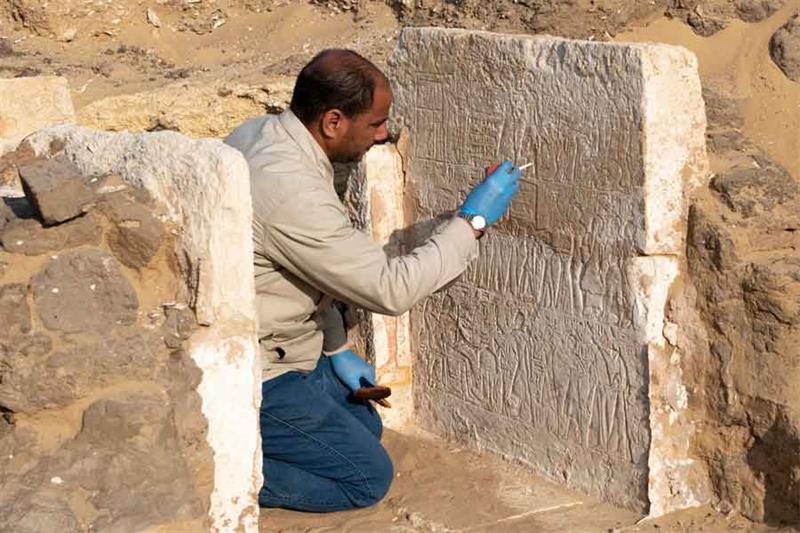

In turn, the archaeologist Mendicuti Pérez explained that the monument was found in an inverted position, 58 centimeters from the surface, which suggests that it was part of the east wall of the aforementioned arch, and its final position was due to its collapse.

He explained that it is a disc composed of rock of sedimentary origin, recognized by the geographer Arlette Herver Santamaría. The glyphic band, present on the front face, measures approximately six centimeters wide, which surrounds an iconographic interior record 20 centimeters in diameter: the iconographic and epigraphic study, headed by the responsible archaeologist, Santiago Alberto Sobrino Fernández, has identified two characters dressed as ball players, standing in front of a ball.

“The character on the left wears a feathered headdress and a sash that features a flower-shaped element, probably a water lily. At the height of his face, a scroll can be distinguished, which can be interpreted as breath or voice. The opponent wears a headdress known as a ‘snake turban’, whose representation is seen on multiple occasions in Chichén Itzá.

The individual wears ballcourt protectors. The epigraphic band consists of 18 cartouches with a short count date of 12 Eb 10 Cumku, which tentatively points to AD 894.

Pérez Ruiz announced that the study of the piece will be carried out within the Promeza; At the moment, its conservation is already being attended to.

Meanwhile, the movable property restorer, Claudia Alejandra Mei Chong Bastidas, desalinated the piece with cellulose fiber compresses and physical-chemical cleaning with distilled water.

In turn, the biologist Luis Alberto Rodríguez Catana has carried out the photogrammetry process, in order to have high-resolution images of the details of the iconography and the glyphic text, to later be studied down to the smallest detail, the researcher concluded.