Ancient Egyptian Head Cones Were Real, Grave Excavations Suggest

Most of the garments depicted in ancient Egyptian art are relatively straightforward to decipher, but there’s a particular wearable article that has baffled archaeologists. In statuary, murals, funerary stelae, coffins and relief sculptures dating between 3,570 and 2,000 years ago, people repeatedly appeared wearing cones on their heads, a bit like party hats.

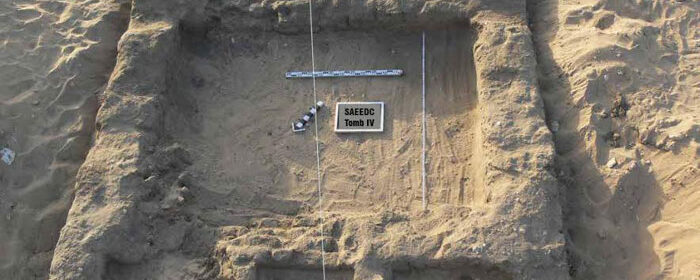

Now, for the first time, archaeologists have actually identified two such cones, crafted out of wax and adorning the heads of skeletons dating back some 3,300 years. The finds were excavated from the cemeteries of the city of Akhetaten, also known as Amarna.

This discovery may finally help to resolve several hypotheses over the meaning of these head cones, and what their function may have been back in the day.

“The excavation of two cones from the Amarna cemeteries confirms that three-dimensional, wax-based head cones were sometimes worn by the dead in ancient Egypt, and that access to these objects was not restricted to the upper elite,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

“The Amarna discovery supports the idea that head cones were also worn by the living, although it remains difficult to ascertain how often and why.”

Akhetaten itself is a curiosity. The city was set up by the Pharaoh Akhenaten, who famously went religiously rogue, setting up his own cult to the sun-god Aten. He established Akhetaten as his capital city in around 1346 BCE, but his attempt to steer Egypt to a new religion was not popular, and Akhetaten was abandoned not long after the Pharaoh’s death in 1332 BCE.

In art discovered in the city, as well as Egypt at large, the head cone makes a not-infrequent appearance. It’s often depicted on the heads of guests at a banquet, or tomb owners participating in funerary rituals or being rewarded by a king.

The cones are also found in depictions of people fishing and hunting in the afterlife and playing music. And the somewhat unusual headgear seems to have a particular association with childbirth, fertility and healing.

The two skeletons found wearing the cones at Akhetaten belonged to a woman around 29 years of age, and an individual whose sex has not been determined, aged between 15 and 20 years.

The woman, excavated in 2010, was in good condition, still intact as she had been laid to rest. She still retained her hair; tangled up in it was the cone, broken apart and burrowed through by insects, but recognisable.

Interestingly, a pattern imprinted on the inside of the cone seemed consistent with fabric weave, as though the interior of the wax structure had been lined.

The grave of the second individual, excavated in 2015, had been robbed, leaving the skeleton jumbled together at the foot of the grave. However, it too had retained hair; and in this hair, the researchers identified a second cone.

Although these discoveries don’t reveal the purpose of the cones, they do narrow things down a bit. For instance, both burials were simple and uninscribed, from a cemetery interpreted as belonging primarily to labourers.

This could mean that either the head cones were not just for high-status members of society but for everyone; or, as also inferred from a recently discovered burial, that the workers copied what they saw the nobility doing.

It also casts some light on hypotheses regarding the purpose of these cones. One idea suggests that the cones were symbolic – like the halos that appear around the heads of Western saints – and not actually a real object. Obviously, this discovery of two actual cones puts that one to bed.

Another hypothesis considered the cones to be solid lumps of scented unguent, or filled with scented fat, which would melt and leak down out of the cone, scenting the wearer’s hair and body in a ritual purification practice. Careful analysis of the cones, however, found no traces of either fat or perfume, nor was there any melted stuff in the wearers’ hair.

Rather, the cones seemed to have been a hollow shell, shaped around or reinforced by fabric. It is possible that they were “dummy” cones created just for burial purposes, and that hats worn by the living were constructed differently, but it also seems possible that the cones could have been a type of formal ritual hat.

“There is no reason to assume .. that hollow – or perhaps textile-lined/-stuffed – cones of wax were not also worn in life. Even if scented, they may not have been intended to melt en masse and moisturise, serving more to mark the wearer as someone who was in a purified, protected or otherwise ‘special’ state,” the researchers write.

“In the case of ancient Akhetaten, we can probably interpret head cones as part of a suite of personal accoutrements deemed appropriate for use in a range of celebrations and rituals for, and involving, the living, the dead, the Aten and other deities.”