The Yakhchāl was an ancient Persian “the refrigerator” that stored food and even ice long before electricity was invented

The ancients were smarter than certain individuals think today. They had no rockets and electricity, no undisputed evidence of such techniques has been discovered, but they have developed technology which we generally do not associate with the ancient world.

The yakhchal (meaning ice pit) was a kind of old coolant constructed in the deserts of Persia (now Iran), which was made without electricity, with contemporary coolants, or with most contemporary coolers. It shows humans ‘ capacity of humans to find solutions to problems with any materials or technology they have available.

Take the Incas, for example, who did not have a developed alphabetic system for writing but had the quipu, a counting device of knots and strings that enabled them to keep track of population records and livestock and even recaptured essential episodes of their folklore.

When it comes to engineering, architectural wonders are omnipresent on almost every continent, whether that be the pyramids of Egypt, Angkor Wat of the Khmer Empire, or even entire underground cities such as Derinkuyu in Turkey’s Cappadocia region.

One great example of smart and sustainable engineering brings us to the Middle East, a realm noted for being one of the cradles of civilization and developing human cultures. There, around the 4th century B.C., the ancient Persians came up with what is known as yakhchāl.

The yakhchāl did not serve as a burial ground or a place to accommodate people, but it instead fulfilled another important function amid the scorching summers.

With excessive heat and arid climate, the region had occupants, the ancient Persians, who needed some way to cool off and store food during the summer months, and that’s when yakhchāls were found of great help.

The word stands for “ice pit.” These edifices provided both space and conditions to store not only ice but also many types of food that would otherwise quickly spoil at hot temperatures.

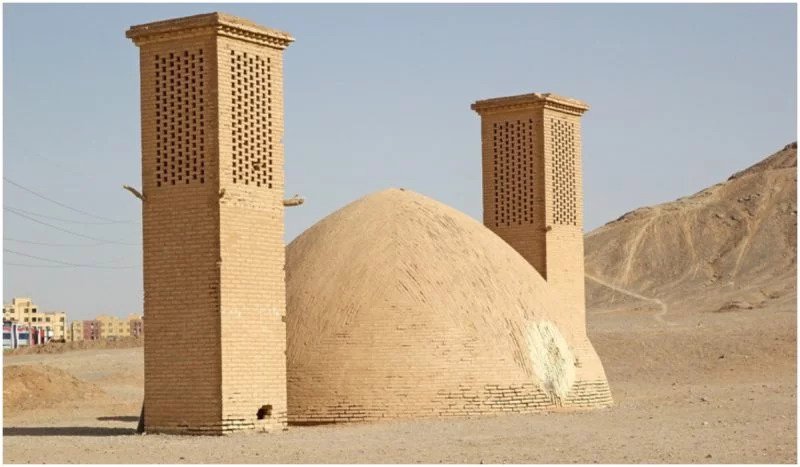

On the outside, a yakhchāl structure can dominate the skyline with its domed shape, and on the inside, it would typically integrate an evaporation cooler system that allowed the ice and food resources to stay cool or even frozen while stored in the structure’s underground rooms.

It may sound a bit far-fetched that the ancient Persians saved ice in the middle of the desert, but their technique was, in essence, not so complicated.

A typical yakhchāl edifice would rise some 60 feet, and on the inside, it would contain vast spaces for storage. The leading examples point to figures such as 6,500 cubic yards in volume.

The evaporative cooling system inside the structures functioned through windcatchers and water brought from nearby springs via qanāts, common underground channel systems in the region designed to carry water through communities and different facilities.

The evaporative cooling allowed temperatures inside the yakhchāl to decrease with ease, giving a chill feeling that indeed you are standing inside one big refrigerator.

The walls of it were constructed intelligently as well, with the usage of special mortar that provided super insulation and protection from the hot desert sun. It was a mix of sand, clay, and other components such as egg whites and goat hair among others.

The structures also contained trenches at the bottom, designed to collect any water coming from molten ice. Once collected, this water was then refrozen during nighttime, making maximum use of the resource as well as the cold desert night temperatures. It was a repetitive process.

Not only did the yakhchāls provide basic food resources, treats, and ice for the royals and high state officials, but the service was so attainable that even the poorest of society could access it.

Usage of yakhchāls has halted in modern times, and though some structures have been damaged and eroded by desert storms, still, many can be found intact across Iran and some of its neighboring countries, as far as to Tajikistan.

The usage of the term yakhchāl lingers on in the region today, commonly referring to refrigerators found in modern-day kitchens.