7,000 Years old Stone Structures Investigated in Saudi Arabia

According to a statement released by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, an international team of researchers analyzed satellite imagery and conducted field surveys to document hundreds of massive rectangular stone structures in northwestern Saudi Arabia, and discover more than one hundred additional structures.

Known as “mustatils,” the rectangular monuments are thought to have been constructed by pastoralists for ritual use. Most of them consist of two large platforms connected by long, low, parallel walls, and some locations have multiple structures built right next to each other.

They give insights into how early pastoralists survived in the challenging landscapes of semi-arid Arabia.

The last decade has seen rapid development in the archaeology of Saudi Arabia. Recent discoveries range from early hominin sites hundreds of thousands of years old to sites just a few hundred years old.

One enigmatic aspect of the archaeological record of western Arabia is the presence of millions of stone structures, where people have piled rocks to make different kinds of structures, ranging from burial tombs to hunting traps. One enigmatic form consists of vast rectangular shapes. Archaeologists working with the AlUla Royal Commission gave these the name ‘mustatils,’ which is Arabic for the rectangle.

Mustatils only occur in northwest Saudi Arabia. They had been previously recognized from satellite imagery and as they were often covered by younger structures, it had been speculated that they might be ancient, perhaps extending back to the Neolithic.

In this new article led by Dr. Huw Groucutt (group leader of the Extreme Events Research Group which is a Max Planck group spanning the Max Planck Institutes for Chemical Ecology, the Science of Human History, and Biogeochemistry) an international team of researchers under the auspices of the Green Arabia Project (a large project headed by Prof. Michael Petraglia from the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the Saudi Ministry for Tourism as well as collaborators from multiple Saudi and international institutions) conducted the first every detailed study of mustatils.

Through a mixture of field surveys and analyzing satellite imagery, the team has considerably extended knowledge of these enigmatic stone structures.

More than one hundred new mustatils have been identified around the southern margins of the Nefud Desert, between the cities of Ha’il and Tayma, joining the hundreds previously identified from studies of Google Earth imagery, particularly in the Khaybar area.

The team found that these structures typically consist of two large platforms, connected by parallel long walls, sometimes extending over 600 meters in length.

The long walls are very low, had no obvious openings, and are located in diverse landscape settings. It is also interesting that little in the way of other archaeology – such as stone tools – was found around the mustatils. Together these factors suggest that the structures were not simply utilitarian entities for something like water or animal storage.

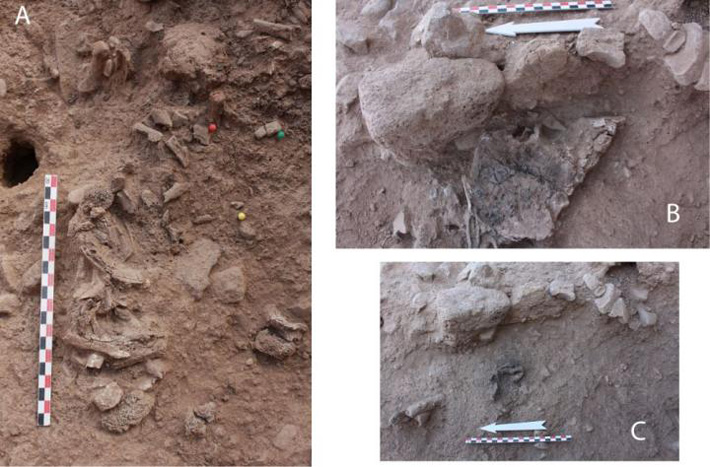

At one locality the team was able to date the construction of a mustatil to 7,000 thousand years ago, by radiocarbon dating charcoal from inside one of the platforms.

An assemblage of animal bones was also recovered, which included both wild animals and possibly domestic cattle, although it is possible that the latter are wild auroch. At another mustatil the team found a rock with a geometric pattern painted onto it.

“Our interpretation of mustatils is that they are ritual sites, where groups of people met to perform some kind of currently unknown social activities,” says Groucutt. “Perhaps they were sites of animal sacrifices or feasts.”

The fact that sometimes several of the structures were built right next to each other may suggest that the very act of their construction was a kind of social bonding exercise. Northern Arabia 7,000 years ago was very different from today.

Rainfall was higher, so much of the area was covered by grassland and there were scattered lakes. Pastoralist groups thrived in this environment, yet it would have been a challenging place to live, with droughts at a constant risk.

The team’s hypothesis is that mustatils were built as a social mechanism to live in this challenging landscape. They may not be the oldest buildings in the world, but they are on a uniquely large scale for this early period, more than two thousand years before pyramids began to be constructed in Egypt.

Mustatils offer fascinating insights into how humans have lived in challenging environments and future studies promise to be extremely useful at understanding these ancient societies.