Ancient mummy ‘with 1,100-year-old Adidas boots’ died after she was struck on the head

Fascinating new details have emerged concerning a medieval mummy known for her Adidas boots which she wore over a thousand years ago. The woman’s body was discovered in the Altai mountain region of Mongolia a year ago.

Yet her body yet her belongings have been so beautifully protected that experts are still uncovering some of the secrets they keep. Now, scientists have discovered that the mummy suffered a significant blow to the head before her death.

The Mongolian woman – aged between 30 and 40 – hit headlines, thanks to her modern-looking footwear, which some likened to a pair of trainers.

In the intervening 12 months, scientists have been working to find out more about the mysterious Mongolian mummy. And her trademark felt boots – boasting red and black stripes – have been carefully cleaned, with new pictures revealed by The Siberian Times.

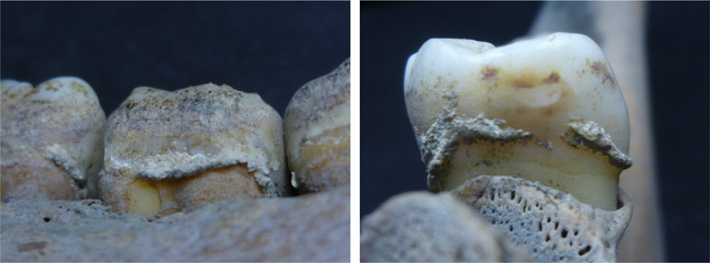

Experts from the Centre of Cultural Heritage of Mongolia now believe the woman died up to 1,100 years ago after suffering a serious head wound.

Initial examinations found that ‘it was quite possible that the traces of a blow to the mummy’s facial bones were the cause of her death’.They are still seeking to verify the exact age of the burial, but they estimate it took place in the tenth century – more recently than originally thought.

About the boots, Galbadrakh Enkhbat, director of the Centre, said: ‘With these stripes, when the find was made public, they were dubbed similar to Adidas shoes.

‘In this sense, they are an interesting object of study for ethnographers, especially so when the style is very modern.’

And one local fashion expert. quoted by Siberian Times, said: ‘Overall they look quite kinky but stylish – I wouldn’t mind wearing them now in a cold climate.

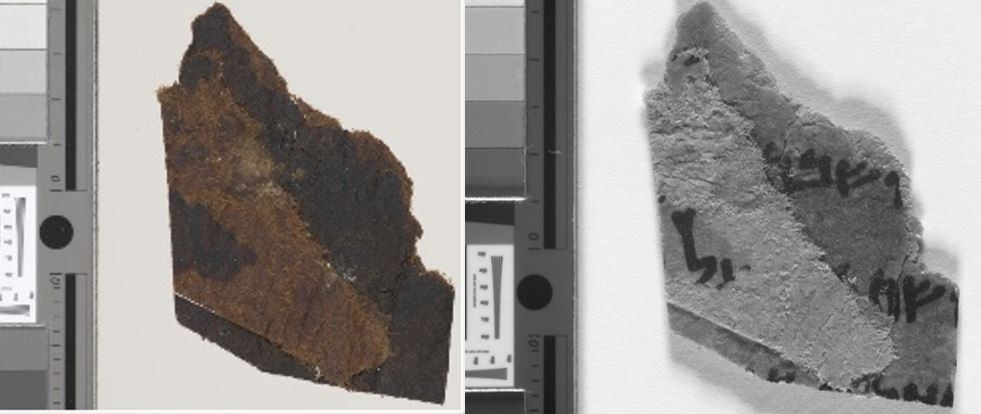

‘Those high-quality stitches, the bright red and black stripes, the length – I would buy them now in no time.’ The high altitude and cold climate helped to preserve both the woman’s body and her belongings. And a coating of Shilajit – a thick, sticky tar-like substance with a colour ranging from white to dark brown – that covered her body aided this process.

Some skin and hair can be seen on her remains, which were wrapped in felt. The woman was buried alongside a number of her possessions – including a handbag and four changes of clothes.

A comb and a mirror from her beauty kit were also found, along with a knife. Her horse and a saddle with metal stirrups in such good condition that it could be used today were buried as well. But despite her seemingly lavish possessions archaeologists believe she was an ‘ordinary’ women of her time, rather than an aristocrat or royal.

‘Judging by what was found inside the burial, we guess that she was from an ordinary social stratum,’ added Mr. Enkhbat.

‘Various sewing utensils were found with her.

‘This is only our guess, but we think she could have been a seamstress.’

‘Inside (her bag) was the sewing kit and since the embroidery was on both the bag and the shoes, we can be certain that the embroidery was done by locals.’ The grave was unearthed at an altitude of 9,200ft (2,803 meters) and the woman is believed to be of Turkik origin.

It appears to be the first complete Turkic burial in Central Asia. At the time of the discovery, commenters on Twitter and Facebook made a number of tongue-in-cheek claims that woman must be a time traveller.

One Twitter user jokingly quipped: ‘Must be a time traveler. I knew we would dig one up sooner or later’, another added: ‘Huh? Time-travelling Mummy? Corpse interfered with?.’

Meanwhile, Facebook users said: ‘Loooooool he’s wearing a pair of gazelles’, and ‘Well I must admit, I’ve got a few pair but I ain’t had them that long.’

A host of possessions were found in the grave, offering a unique insight into life in medievMongolia. These included a saddle, bridle, clay vase, wooden bowl, trough, iron kettle, the remains of an entire horse, and ancient clothing.

There were also pillows, a sheep’s head, and felt travel bag in which were placed the whole back of a sheep, goat bones, and small leather bag designed to carry a cup. Archaeologists from the city museum in Khovd were alerted to the burial site by local herdsmen. The Altai Mountains – where the burial was discovered – unite Siberia, in Russia, and Mongolia, China and Kazakhstan.