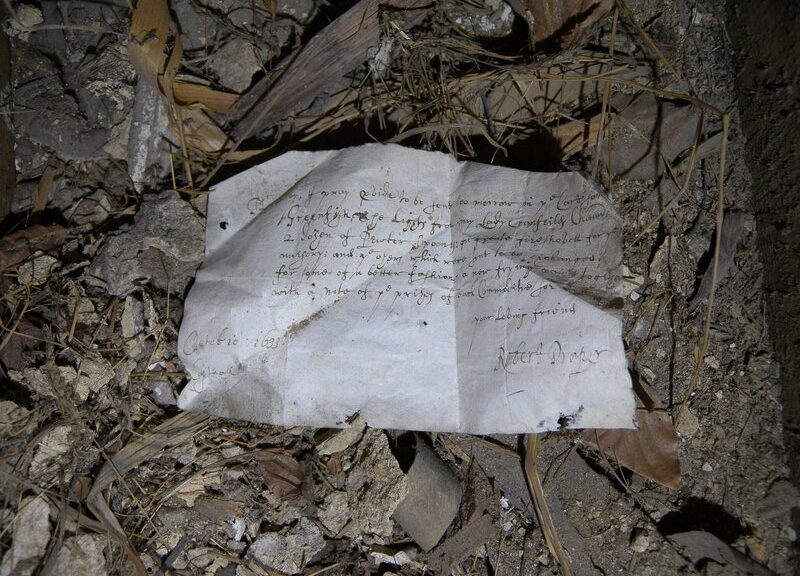

387-Year-Old Shopping List Discovered Under Floorboards In Historic English Home

Such must-have items were listed on a shopping list 387 years back, including pewter spoons, frying cups and “greenfish.” Under the floors of Knole, a historic country house in Kent, England, a scrap of paper has recently been discovered.

Jim Parker, an archeology volunteer at Knole, has found the 1633 note for the restoration of the building, as reported for Kent Live by Oliver Porritt.

The team also found two other 17th century letters nearby. One, like the shopping list, was located under the attic floorboards; another was stuffed into a ceiling void.

The shopping list was penned by Robert Draper and addressed to one Mr. Bilby.

According to the UK’s National Trust, the note was “beautifully written,” suggesting that Draper was a high-ranking servant.

In addition to the aforementioned kitchenware and greenfish (unsalted cod), Draper asks Mr. Bilby to send a “fire shovel” and “lights” to Copt Hall (also known as Copped Hall), an estate in Essex. The full text reads:

Mr. Bilby, I pray p[ro]vide to be sent too morrow in ye Cart some Greenfish, The Lights from my Lady Cranfeild[es] Cham[ber] 2 dozen of Pewter spoon[es]: one greate fireshovell for ye nursery; and ye o[t]hers which were sent to be exchanged for some of a better fashion, a new frying pan together with a note of ye prises of such Commoditie for ye rest.

Your loving friend

Robert Draper

Octobre 1633

Copthall

How did this rather mundane domestic letter come to be stashed in an attic at Knole, which is some 36 miles away from Copt Hall? As the National Trust explains, Copt Hall and Knole merged when Frances Cranfield married Richard Sackville in 1637.

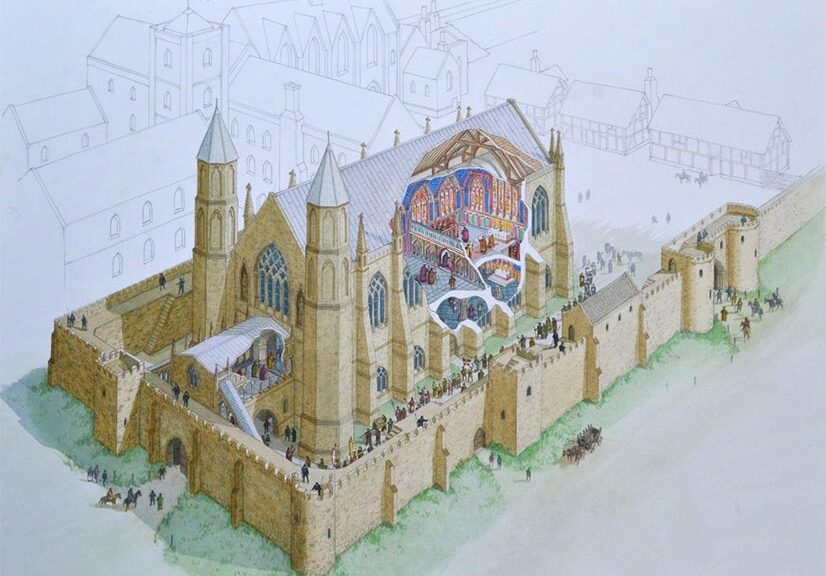

Cranfield was the daughter of the Earl of Middlesex, who owned Copt Hall; Sackville, the 5th Earl of Dorset, had inherited Knole, his family’s home.

Household records indicate that large trunks filled with domestic items—including various papers—were moved from Copt Hall to Knole at the time of the marriage, and subsequently stored in the attic. Draper’s note may have slipped under the floorboards.

The marriage of Cranfield and Sackville was important for Knole, according to the National Trust Collections, because Cranfield inherited a trove of expensive paintings and furniture from her father.

Draper’s letter certainly was not among the more prized items that Cranfield brought to the marriage, but for modern-day historians, it is exceptionally valuable.

“It’s extremely rare to uncover letters dating back to the 17th century, let alone those that give us an insight into the management of the households of the wealthy, and the movement of items from one place to another,” Nathalie Cohen, regional archaeologist for the National Trust, tells Porritt.

She added that the good condition of both the list and the two other letters found at Knole “makes this a particularly exciting discovery.”