Treasures dating back some 9,500 years is uncovered in Alpine glaciers as climate change causes ice to melt

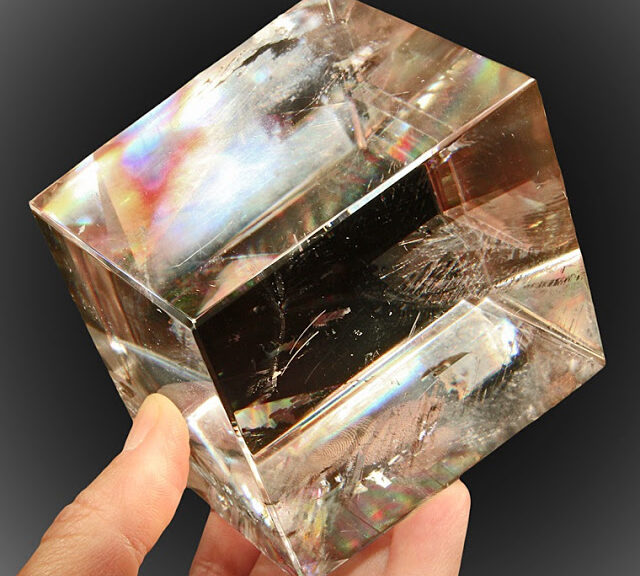

The group climbed the steep mountainside, clambering across an Alpine glacier, before finding what they were seeking: A crystal vein filled with the precious rocks needed to sculpt their tools. That is what archaeologists have deduced after the discovery of traces of an ancient hunt for crystals by hunters and gatherers in the Mesolithic era, some 9,500 years ago.

It is one of many valuable archaeological sites to emerge in recent decades from rapidly melting glacier ice, sparking a brand-new field of research: glacier archaeology. Amid surging temperatures, glaciologists predict that 95 per cent of some 4,000 glaciers dotted throughout the Alps could disappear by the end of this century.

While archaeologists lament the devastating toll of climate change, many acknowledge it has created “an opportunity” to dramatically expand understanding of mountain life millennia ago.

“We are making very fascinating finds that open up a window into a part of archaeology that we don’t normally get,” said Marcel Cornelissen, who headed an excavation trip last month to the remote crystal site near the Brunifirm glacier in the eastern Swiss canton of Uri, at an altitude of 2,800 metres (9,100 feet).

‘Truly exceptional’

Up until the early 1990s, it was widely believed that people in prehistoric times steered clear of towering and intimidating mountains. But a number of startling finds have since emerged from melting ice indicating that mountain ranges like the Alps have been bustling with human activity for thousands of years.

Early humans are now believed to have hiked up into the mountains to travel to nearby valleys, hunt or put animals out to pastures, and to search for raw materials. Christian Auf der Maur, an archaeologist with Uri canton who participated in the crystal site expedition, said the find there was “truly exceptional.”

“We know now that people were hiking up to the mountains to up to 3,000 metres altitude, looking for crystals and other primary materials.”

The first major ancient Alpine find to emerge from the melting ice was the discovery in 1991 of “Oetzi,” a 5,300-year-old warrior whose body had been preserved inside an Alpine glacier in the Italian Tyrol region. Theories that he may have been a rare example of a prehistoric human venturing into the Alps have been belied by findings since of numerous ancient traces of people crossing high altitude mountain passes.

Rare organic materials

The Schnidejoch pass, a lofty trail in the Bernese Alps 2,756 metres (9,000 feet) above sea level, has for instance been a boon to scientists since 2003, with the find of a birch bark quiver – a case for arrows – dating as far back as 3,000 BCE. Later, leather trousers and shoes, likely from the same ill-fated person, were also discovered, along with hundreds of other objects dating as far back as about 4,500 BCE.

“It is exciting because we find stuff that we don’t normally find in excavations,” archaeologist Regula Gubler told AFP. She pointed to organic materials like leather, wood, birch bark, and textiles, which are usually lost to erosion but here have been preserved intact in the ice.

Just last month, she led a team to excavate a fresh finding in Schnidejoch: a knotted string of bast – or plant – fibres believed to be over 6,000 years old. It resembles the fragile remains of a blackened bast-fibre, braided basket from the same period, brought back last year.

While climate change has made possible such extraordinary finds, it is also a threat: if not found quickly, organic materials freed from the ice rapidly disintegrate and disappear.

‘Very short window’

“It is a very short window in time. In 20 years, these finds will be gone and these ice patches will be gone,” Gubler said. “It is a bit stressful.”

Cornelissen agreed, saying the understanding of glacier sites’ archaeological potential had likely come “too late”.

“The retreat of the glaciers and melting of the ice fields has already progressed so far,” he said. “I don’t think we’ll find another Oetzi.”

The problem is that archaeologists cannot hang out at each melting ice sheet waiting for treasure to emerge. Instead, they rely on hikers and others to alert them to finds. That can sometimes happen in a roundabout way.

When two Italian hikers in 1999 stumbled across a wood carving on the Arolla glacier in southern Wallis canton, some 3,100 metres above sea level, they picked it up, polished it off, and hung it on their living room wall. It was only through a string of lucky circumstances that it 19 years later came to the attention of Pierre Yves Nicod, an archaeologist with the Wallis historical museum in Sion, where he was preparing an exhibition about glacier archaeology.

He tracked down the 52-centimetre-long human-shaped statuette, with a flat, frowning face, and had it dated. It turned out to be over 2,000 years old – “a Celtic artefact from the Iron Age,” Nicod told AFP, lifting up the statuette with gloved hands. Its function remains a mystery, he said.

Another unknown, Nicod said, is “how many such objects have been picked up throughout the Alps in the past 30 years and are currently hanging on living room walls.

“We need to urgently sensibilise populations likely to come across such artifacts.” “It is an archaeological emergency.”