3,000-year-old Treasure on the Iberian Peninsula made with material from a meteorite

Scientists have recently discovered that some of the pieces in the amazing Bronze Age collection known as the Villena Treasure, which was found in Spain more than 60 years ago, contain iron that came from an alien meteorite that crashed into Earth about a million years ago.

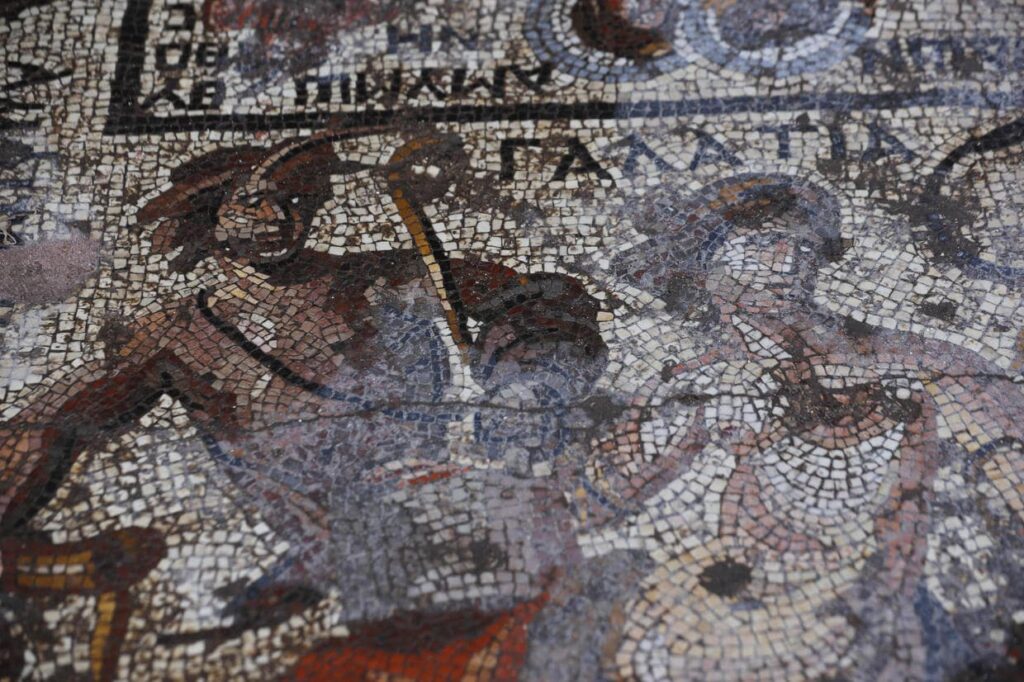

Treasure of Villena contains artifacts fashioned from precious materials like gold, silver, amber, and iron. Each piece within this collection tells a story of the culture, technology, and traditions of the people who lived during the Bronze Age, between 1400 and 1200 B.C.

Scientists who have delved deeper into the origins and structure of the Villena Treasure are now revealing unexpected information.

They concluded that some of the objects were made from extraterrestrial material. Specifically, meteoric iron, a material originating in space, was identified in some of the artifacts.

A remarkable discovery regarding this old hoard has been made possible by recent research: two of the iron objects were made with iron that fell to Earth from a meteorite some million years ago.

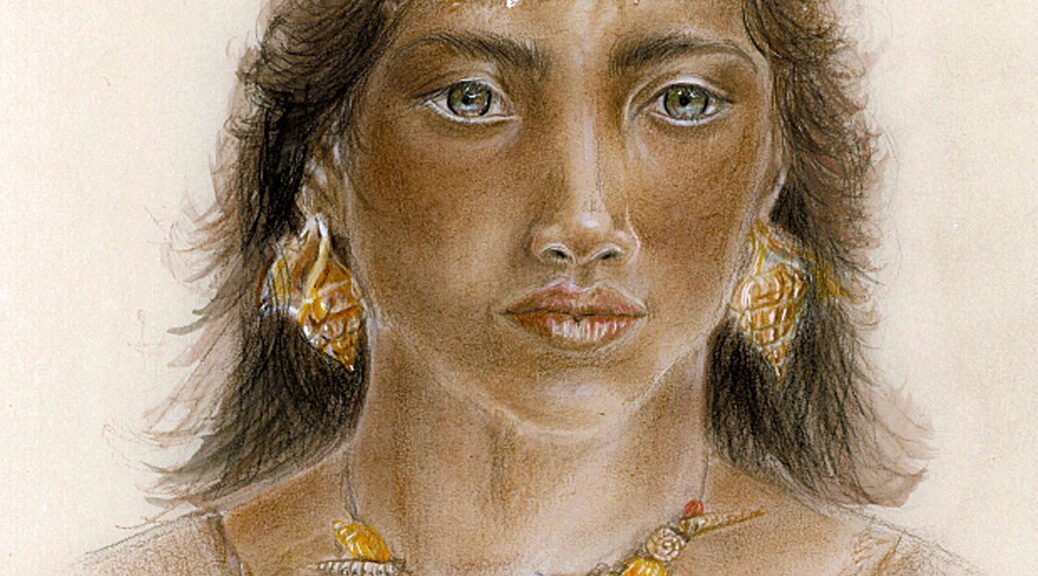

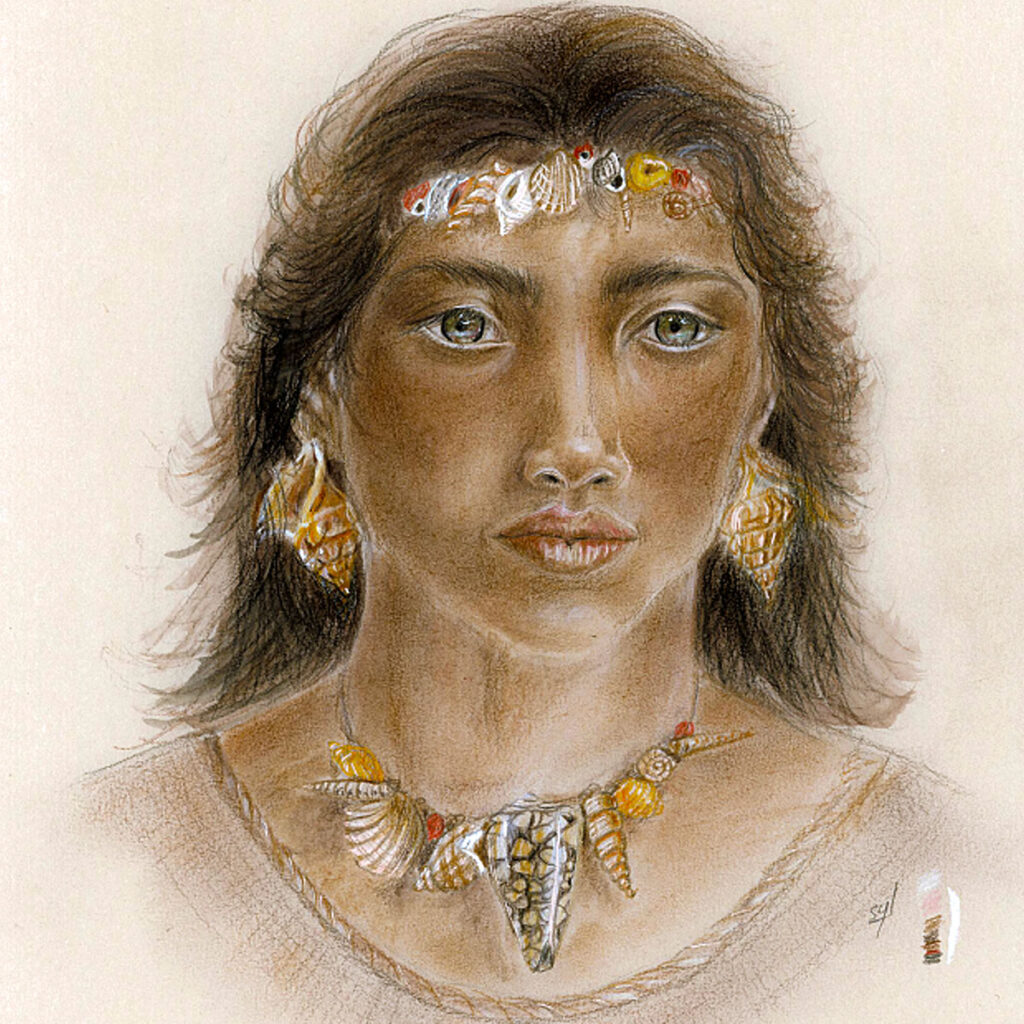

The objects, a hollow sphere covered in gold sheeting and a bracelet in the form of a C, were symbols of a link between the earthly and heavenly realms in addition to being exquisite examples of prehistoric handiwork.

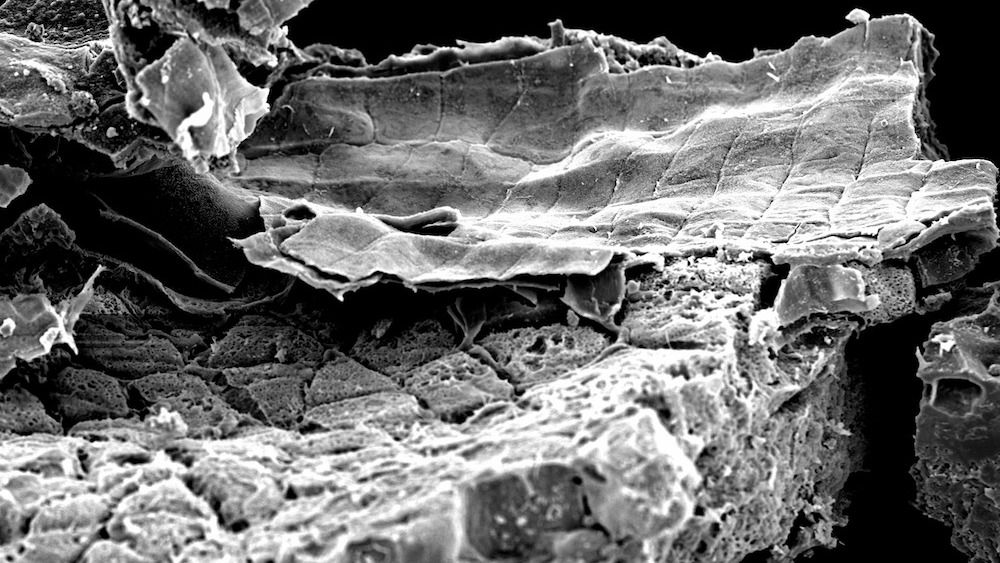

At the time of its discovery, certain iron elements had intrigued researchers due to their distinctive appearance, evoking a leaded metal, shining in places and covered in an oxide resembling iron.

The research, published on December 30 in the journal Trabajos de Prehistoria, analyzed two iron pieces.

The study reveals that the iron used for these artifacts indeed comes from a meteorite, thanks to spectrometric mass analyses that identified an iron-nickel alloy similar to that of meteoritic iron.

According to the research team’s findings, one of the Spanish treasures, an iron bracelet, was fashioned from iron and nickel. This is significant since meteoric iron usually contains over 5 percent nickel.

These are the first and oldest meteoritic iron artifacts discovered on the Iberian Peninsula. They shed light on Late Bronze Age metallurgical practices while also demonstrating how these cultures innovated with new technologies. As a result, these artifacts serve not only as historical treasures but also as windows into the past, providing insight into the development of new technologies and societal evolution.

These objects join the rare artifacts of meteoritic iron known from the first millennium BC, such as an arrowhead discovered in Switzerland and some objects in Poland.

So far, the data suggests that the composition of the Spanish artifacts is similar to that of the Mundrabilla meteorite from Australia. However, it is currently impossible to say with certainty that ancient populations used the materials from this specific meteorite to create these valuable treasures. The researchers intend to conduct additional investigations in the future.