The First Temple At Gobekli Tepe: Denisovan & Anunnaki Ancient Aliens Origins

Gobekli Tepe is the oldest known ancient site at the age of 12,000 and is undoubtedly the first known Temple in the world. At least 7,000 years before the Sumerian Empire, its presence raises questions as to how the history of civilization and the early days of the modern man can be traced.

Excavation at the site suggests that the findings present a challenge to both mainstream and alternative historical accounts such as the Ancient Astronaut Theory. The result is an enigma that points to the possibility that the Gobekli Tepe site as the World’s first temple was built either by the Native inhabitants, the Denisovans, or the Anunnaki Ancient Aliens.

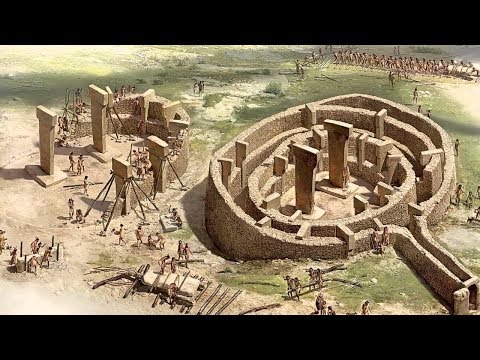

The Gobekli Tepe Temple Complex Site

Located in Turkey, Gobekli Tepe is made up of a vast Stone Temple Complex. However, unlike Sumerian or Ancient Egyptian Temple Complexes, there is no writing from which the purpose of the Complex can be understood. Instead, we have a Stone alignment and a series of symbolic inscriptions that suggest the existence of an Astronomy based Religion.

The Gobleki Tepe Site’s alignment to the Cygnus constellation and as a means of marking the Precession of the Equinoxes in Ancient times has been proposed by Andrew Collins and Graham Hancock.

In addition, the Temple inscriptions bear a close resemblance to the symbols that would be used later in Sumerian, Indus Valley, Egyptian and Mesoamerican Temples. It would, therefore, appear that Gobleki Tepe is possibly the site at which the Astronomical Religions of the Ancient world began.

Gobleki Tepe is also credited with being the source of the agricultural knowledge that was later transmitted to these later Ancient Civilizations.

Whilst the Astronomical alignments and Religious symbols at Gobleki Tepe are fairly clear, the identity of the Architects remains a mystery.

The Unknown Architects Of Gobekli Tepe

Without a doubt, the Architects of Gobleki Tepe were of superior intelligence and culture. According to Andrew Collins and Graham Hancock, the Architects were possibly the Denisovans, a now extinct Giant Humanoid hybrid species of superior size and intelligence.

In this view, the builders of Gobleki Tepe may have been the survivors of the great deluge, who established Gobleki Tepe in order to preserve and transmit pre-flood knowledge and culture.

Sitchin’s Ancient Astronaut Theory would also suggest that Gobekli Tepe was a site that was established by the Anunnaki Ancient Aliens after the flood as a means of preserving the pre-flood knowledge.

It has also been argued that the site is the work of local Native Tribes who built the site in Ancient times together with the NAZCA lines using stone tools.

The identity of the Architects of Gobleki Tepe remains an enigma, and it is from its influence on later cultures that perhaps we may obtain some idea as to who is responsible for erecting the Temple Complex.

The Influence Of Gobekli Tepe

Gobleki Tepe’s influence is most evident in the later Civilizations of Sumeria, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and Mesoamerica.

In particular, the symbols and astronomical alignments were first seen at Gobleki Tepe are apparent in these same later Civilizations, forming the foundation of these Civilizations by introducing concepts like Time, Temple Construction, and Religious worship of the Gods.

It would seem the Gobleki Tepe provided a kind of ancient template upon which later Civilizations were built. The references to the Ancient Gods of Sumer, Egypt, India, and Mesoamerica may in-fact be references to the Denovisan founders of the Gobleki Tepe complex who spread the knowledge of Civilization to these regions.

As such, the Ancient Gods in these various regions may in-fact be Giant Hybrid Denovisans rather than Ancient Astronauts as suggested by Zechariah Sitchin. Its therefore possible that the Ancient Gods may not have descended from the Heavens, but were regarded as having done so by the peoples they initiated into the arts of Civilization.

The earliest depictions of the Architects of Gobleki Tepe may possibly be of the Serpent figures of the Ubaid Culture which may be seen as portrayals of Denivosan Giants rather than Alien beings.

Gobleki Tepe culture may have therefore spread and established itself in the Ubaid Region first, then onto Sumer, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and Mesoamerica.

Conclusion

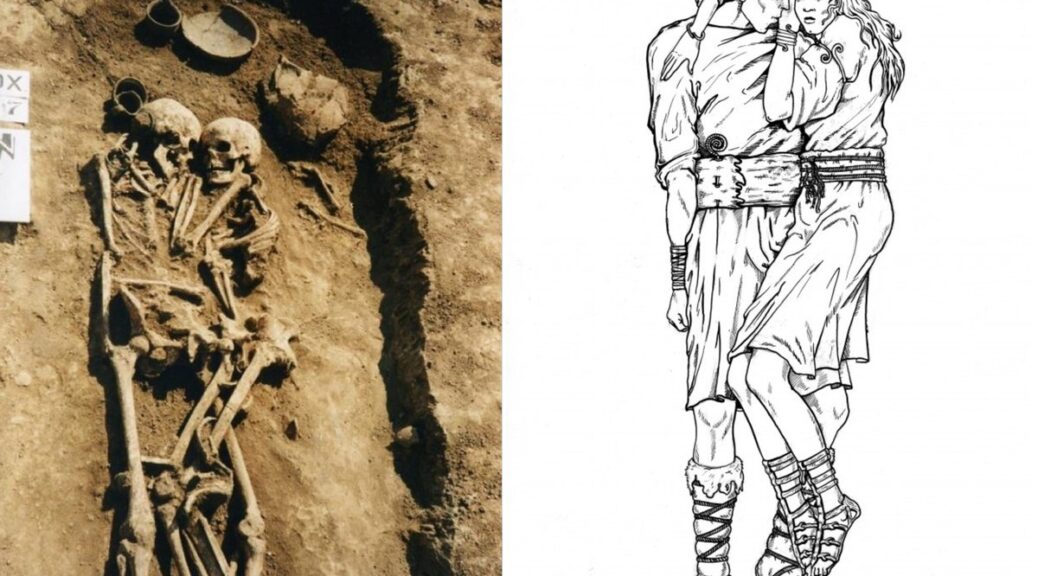

The Giant skeletons that have been unearthed throughout the world and remain unexplained by mainstream Archaeology may belong to the Architects of Gobleki Tepe. A Race of Denovisan Hybrid Giants who initiated all subsequent Cultures into Civilization.

In this sense, Gobekli Tepe may be regarded as some kind of learning center or school for the initiation of early mankind into Civilization after the great deluge. Excavation of the Gobekli Tepe site still continues, and perhaps more revelations will provide clarity as to its purpose, origins, Architects, and influence on later Civilizations.

Nevertheless, at this point, what has been discovered so far brings into question both mainstream history and alternative arguments like Sitchin’s Ancient Astronaut Theory especially if the Denovisan hypothesis is considered.