Neanderthals Enjoyed Seaside Crab Roasts in Portugal

Scientists studying archaeological remains at Gruta da Figueira Brava, Portugal, discovered that Neanderthals were harvesting shellfish to eat – including brown crabs, where they preferred larger specimens and cooked them in fires. Archeologists say this disproves the idea that eating marine foods gave early modern humans’ brains the competitive advantage.

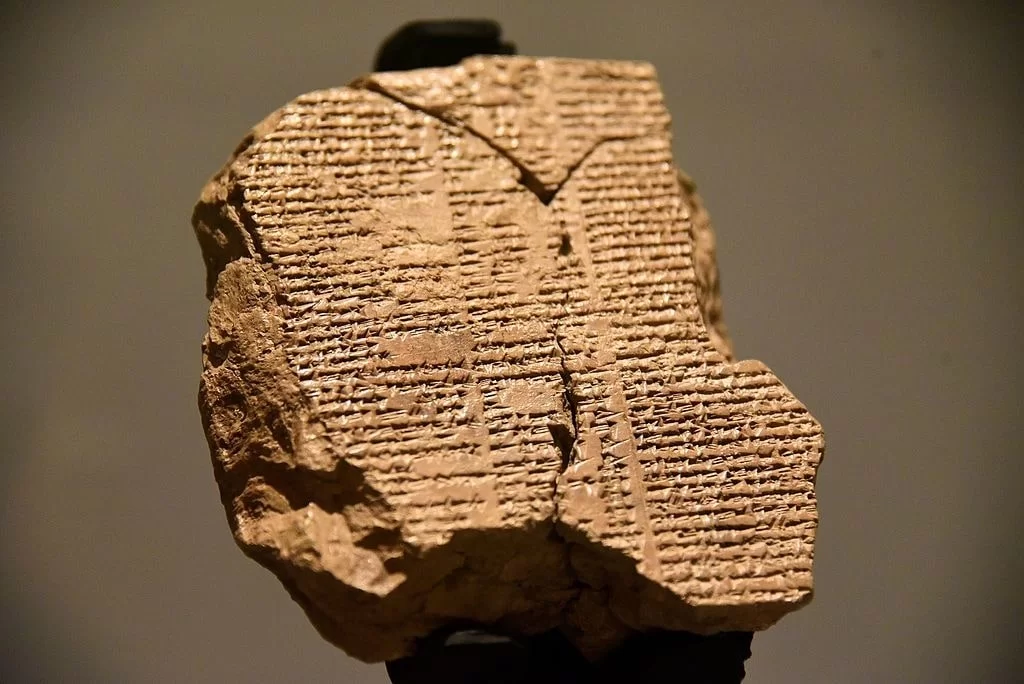

In a cave just south of Lisbon, archeological deposits conceal a Paleolithic dinner menu. As well as stone tools and charcoal, the site of Gruta de Figueira Brava contains rich deposits of shells and bones with much to tell us about the Neanderthals that lived there – especially about their meals.

A study published in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology shows that 90,000 years ago, these Neanderthals were cooking and eating crabs.

“At the end of the Last Interglacial, Neanderthals regularly harvested large brown crabs,” said Dr Mariana Nabais of the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA), lead author of the study.

“They were taking them in pools of the nearby rocky coast, targeting adult animals with an average carapace width of 16cm. The animals were brought whole to the cave, where they were roasted on coals and then eaten.”

Catching crabs in Paleolithic Portugal

A wide variety of shellfish remains were found in the archeological remains Nabais and her colleagues studied, but the shellfish in the undisturbed Paleolithic deposits are overwhelmingly represented by brown crabs. Their size was estimated by calculating the size of the carapace relative to the crabs’ pincers, which preserve better than other parts of the crab, so are more likely to survive to be found by scientists.

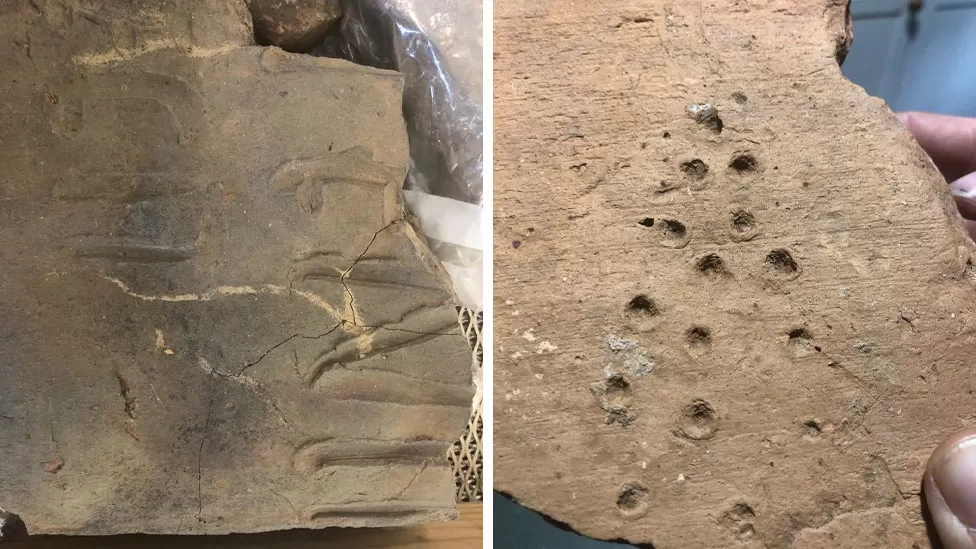

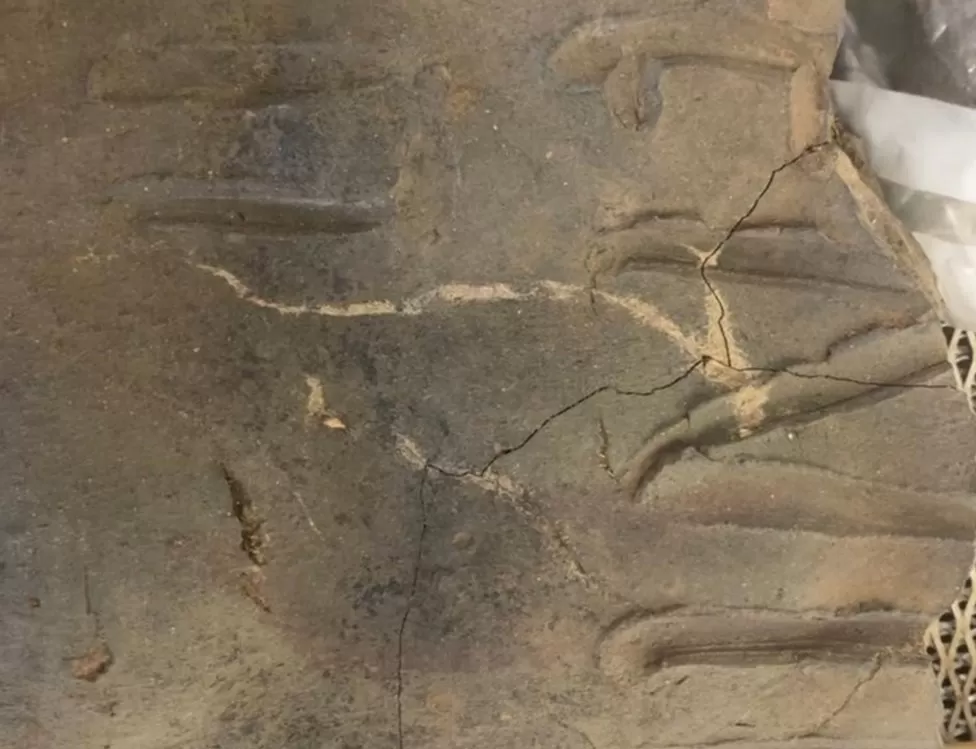

The archeologists assessed the breakage on the shells, looked for butchery or percussion marks, and determined whether the crabs had been exposed to high heat.

Nabais and her colleagues found that the crabs were mostly large adults which would yield about 200g of meat. By studying the patterns of damage on the shells and claws, they ruled out the involvement of other predators: there were no carnivore or rodent marks, and the patterns of breakage didn’t reflect predation by birds. Crabs are evasive, but Neanderthals could have harvested brown crabs of this size from low tide pools in the summer.

Accumulations of shellfish which are caused by hominins are identified by their association with stone tools and other hominin-made features like hearths, surface modifications like the burns found on approximately 8% of the crab shells, and evidence of intentional fractures; the fracture patterns on the crabs at Gruta de Figueira Brava suggested they’d been broken open for access to the meat. The expectation is also that larger individuals will be overrepresented, as at Gruta de Figueira Brava, reflecting hominins choosing animals which offer more meat.

Shellfish on the menu

The evidence indicated to Nabais and her colleagues that Neanderthals weren’t just harvesting the crabs, they were roasting them. The black burns on the shells, compared to studies of other mollusks heated at specific temperatures, showed that the crabs were heated at about 300-500 degrees Celsius, typical for cooking.

“Our results add an extra nail to the coffin of the obsolete notion that Neanderthals were primitive cave dwellers who could barely scrape a living off scavenged big-game carcasses,” said Nabais. “Together with the associated evidence for the large-scale consumption of limpets, mussels, clams, and a range of fish, our data falsify the notion that marine foods played a major role in the emergence of putatively superior cognitive abilities among early modern human populations of sub-Saharan Africa.”

The authors cautioned that it was impossible to know why Neanderthals chose to harvest crabs or whether they attached any significance to consuming crabs, but whatever their reasons eating the crabs would have offered meaningful nutritional benefits.

“The notion of the Neanderthals as top-level carnivores living off large herbivores of the steppe-tundra is extremely biased,” said Nabais. “Such views may well apply to some extent to the Neanderthal populations of Ice Age Europe’s periglacial belt, but not to those living in the southern peninsulas — and these southern peninsulas are where most of the continent’s humans lived all through the Paleolithic, before, during and after the Neanderthals.”